Zoos- good or bad? Of course this issue is by no means that conclusive, but that black or white attitude is the one that most often prevails when arguments are voiced. This topic is often quite a sensitive one, and not just for passionate conservationists. It seems everyone has a relatively steadfast opinion on the necessity of zoological establishments, and it is the debate I most often find myself involved in.

Zoos- good or bad? Of course this issue is by no means that conclusive, but that black or white attitude is the one that most often prevails when arguments are voiced. This topic is often quite a sensitive one, and not just for passionate conservationists. It seems everyone has a relatively steadfast opinion on the necessity of zoological establishments, and it is the debate I most often find myself involved in.

Damien Aspinall (Son of John Aspinall and current Chairman of The Aspinall Foundation) recently stated that if it were in his hands he would “close down 90% of all zoos“. For those who are not familiar with the Aspinalls, this is a very bold and significant statement for such a prominent zoological figure to make. First opened in 1975, Howletts Wild Animal Park was the baby of the eccentric John, who closely followed it with the opening of Port Lympne in 1976, and finally the registered charity The Aspinall Foundation in 1984. There is no denying that the Aspinalls are unorthodox, but I don’t wish to dwell on that here, for regardless of opinions of their conduct they are responsible for two highly acclaimed and very successful zoos.

Many may now be wondering what is meant by a “successful zoo”, a very good question with no absolute answer. In the simplest of terms the success of a captive population is most often related to the success of reproduction, and I think this is a relatively good baseline. Animals will very rarely breed in an environment where they are malnourished, unwell, or fearful (where welfare is compromised) therefore in many cases when captive animals are breeding well this often reflects well on their housing and care. (There are official guidelines that dictate appropriate institutions, addressed in compulsory inspections overseen by DEFRA. See the links here and here for detail on the inspectorate and the Secretary of States Standards for Modern Zoo Practice (SSSMZP) which will be referenced as I continue).

This leads well into a common misconception that captive bred animals are a direct manifestation of conservation. Captive breeding is often considered analogous to Noah’s Ark, threatened species being maintained in captivity until factors putting them at risk in the wild are removed; staying in the ark until the floods pass. Understandable in theory, but in practice zoos do not only house threatened species. Captive breeding is exactly the face value of the words, animals that have been bred in captivity. The ones you see will very rarely be destined for a future in the wild.

So why are they there? If you are a regular visitor to zoos you will often find that you are asked for feedback on your visit, and will commonly be asked why you came. The standard answer is for recreation, for a good day out, and this is often where complications arise. The Zoo Licensing Act (1981) defines a zoo as “an establishment where wild animals are kept for exhibition, to which members of the public have access with or without charge for admission”. Words like ‘recreation’ and ‘exhibition’ are often subconsciously associated with entertainment, and keeping wild animals for entertainment is in gross conflict with conservation.

The Captive Animals Protection Society (CAPS) is an organisation dedicated to ending animal exploitation. They fund and promote efforts to abolish the exotic pet trade, to prevent animals being forced to perform in circuses, and significantly to close all zoos in the UK. They provide a damning explanation of their inclusion of zoos in their aims here.

There is no doubt that some distressing and unsavoury truths are revealed, however for me their work highlights the significant flaws in zoo legislation as opposed to the condemnation of all establishments.

In their own report ‘A License to Suffer‘ (2011) CAPS identify extreme shortcomings in the upkeep of the SSSMZP. They highlight that “An average fully licensed zoo holds over 2,000 animals. Formal inspections should be carried out once every two or three years by qualified government inspectors. Usually lasting no more than one working day, this allows each animal a maximum of 36 seconds of the inspectors’ time. For the largest zoo in England, this is reduced to just 1.4 seconds”. They further explain that this blink of an eye assessment “therefore operates under a culture of exceptions. 84% of zoos have dispensations and only 16 % of zoos have full licences, which would not be the case had DEFRA correctly applied its own criteria”.

CAPS are not alone in their findings, in 2012 The Born Free Foundation also released a report looking at standards across the European Union. The document provides an exceptional insight into the pitfalls of current legislation. In England, this namely lies with the Local Authorities who are tasked with the actual implementation of the Zoo Licensing act, and all financial ties associated with it. In short, there is an absolute conclusion that in many instances Local Authorities are failing to meet the requirements set by DEFRA, and DEFRA are failing to crack the whip.

Born Free suggest that “ The limitations that Local Authorities face with respect to time, funding and expertise should be fully considered and additional support should be provided where necessary to ensure the proper functioning of the licensing system.” with which I fully agree. A well maintained and tight legislature for zoo housed animals, and not a blanket abolition would be my ideal solution as I do feel that zoos have a place in our society.

Captive wild animals in good zoological collections can raise significant awareness vital to conservation. I firmly believe that my own childhood experiences with zoos helped to shape the active and passionate defender of the environment I consider myself to be. Education is paramount to the purpose of a zoo, and in a good zoo you will notice concerted efforts to deliver knowledge via every medium. You should come away feeling improved and inspired, not entertained.

For me, welfare is the front runner in any debate. There is another very lengthy aspect to this observing diets, correct housing, correct social grouping, health risks and more which it is simply not possible to cover in this instance.

Fundamentally there has to be an acceptance that no zoo can recreate the native habitats of it’s occupants, but all zoos can and should uphold their duty of care to the highest of standards. I believe it is possible to create captive environments in which animals can be healthy and stimulated, and it is the responsibility of zoos to put that above visitor experience on their list of priorities. Even the most conscientious zoo visitors are disappointed when they feel they have not ‘seen enough’ on their trip. Zoo education needs to help move society away from one of demand, and towards one of privilege. As a zoo visitor you should be a guest in the animals environment, it should be an experience of uncertainty as to what you will and will not spot throughout your day. This is possible and is just as enjoyable but relies on a dramatic shift in public perceptions.

I fully agree that in-situ habitat protection is the only solution for long term effective conservation. However, as a conservationist I don’t feel a right of exclusivity to the wonders of nature I am able to experience. I hope that zoo visitors are in awe of the things they see, and that that awe can transition into respect, which can develop into vital awareness.

There is no comparable sense of wonder to seeing wildlife first hand, an experience without which my childhood would seem incomplete. Instead of banishing zoos based on their problems, we should help them live up to expectation by rectifying the wrongs.

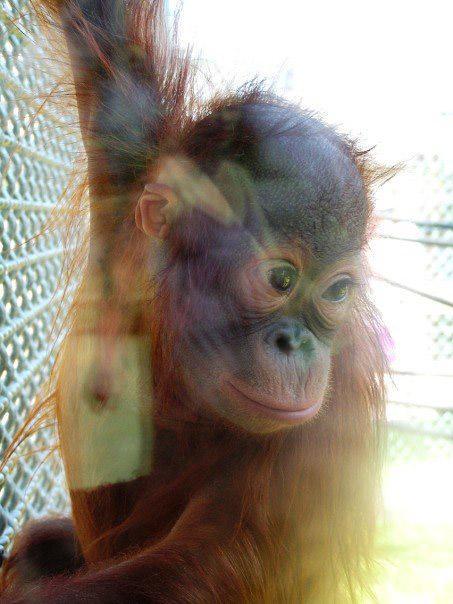

Photo courtesy of Alex Crawford, 2006.