[Part 2 of 2]

The Oregon State University Black Student Union’s (BSU) decision to interrupt a convocation featuring Linus Pauling and to stage a subsequent walkout off of campus were sparked by an incident involving an African American student athlete at OSU. As documented in multiple later accounts, on February 22, 1969 OSU football player Fred Milton broke team rules by refusing to shave his goatee. Although this conflict occurred during the off-season, Oregon State football coach Dee Andros – an ex-Marine affectionately known as “The Great Pumpkin” – believed that he still maintained authority over his players and their appearance. Andros gave Milton a forty-eight hour deadline to comply with the team rule. If he continued to resist, he would be cut from the team, which would mean he would also lose his OSU scholarship.

The BSU took on Milton’s cause and began planning peaceful measures to publicly express their solidarity and to bring awareness to the struggles that African American students were facing on the OSU campus. The actions that the agreed to put in play included a sit-in at a public event, a class boycott, and a campus walkout. The group also began publishing an underground newspaper, The Scab Sheet, which they viewed to be an important alternative to the OSU Daily Barometer, the student daily that had assumed an editorial stance tfavorable to Andros’ perspective.

The BSU believed the Milton case to be an infringement of a student’s rights to individual self-expression. The group also pointed out that this was not the first black student athlete who had come into conflict with Andros’ policies; in the past, others had been told to keep their hair short and to not wear medallions. BSU President Mike Smith explained that, although the policies were extended across the athletic department, they were based on standards set by white society, and that black student athletes were pressured to conform to them.

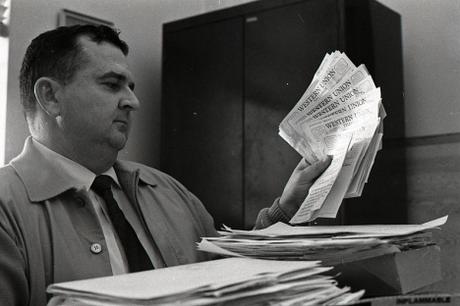

OSU football coach Dee Andros holding telegrams of support, March 1969.

The first of the BSU’s peaceful protest actions began with a sit-in at a campus lecture, which was to be given by Linus Pauling on the morning of February 25, 1969. The speech, titled “Advancement of Knowledge: Ortho-Molecular Psychiatry,” was one of seven presentations scheduled over three days as part of the OSU centenary celebration. The series celebrated the first hundred years of Oregon State by looking toward the future with a general theme of “The Second Hundred Years.” To encourage campus participation, the university cancelled all classes that conflicted with the seven presentations. The formal lectures were to be followed by a discussion period in which students would be given the opportunity to dialog with each of the invited speakers.

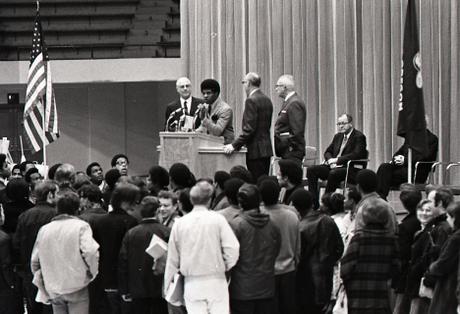

Pauling’s speech is interrupted during his introduction. Pauling, seated, is obscured at right by the state of Oregon flag.

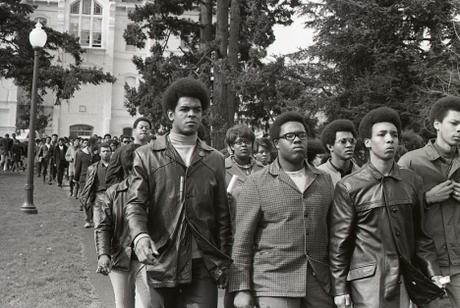

As Pauling was being introduced, an estimated seventy Black Student Union members and supporters filed into Gill Coliseum, the school’s basketball arena and the location for Pauling’s lecture. The BSU students subsequently took control of the dais, while Pauling remained seated. Mike Smith, the BSU president, and sophomore defensive back Rich Harr explained the group’s reasons for staging the interruption and also announced a boycott of athletic events that would start that weekend. The speakers likewise called for white student support, noting that this was not just about the treatment of black student athletes, but of all students on campus. These sentiments were repeated later at a rally held in front of OSU’s Memorial Union.

After about twenty minutes, the protesters left the gym. The large crowd that had assembled for Pauling’s talk gave a mixed response, though the majority of students applauded the BSU’s statements. In an oral history interview conducted in 2011, OSU chemistry professor emeritus Ken Hedberg, a close friends of Pauling’s, remembered the participants as having been “very well behaved.”

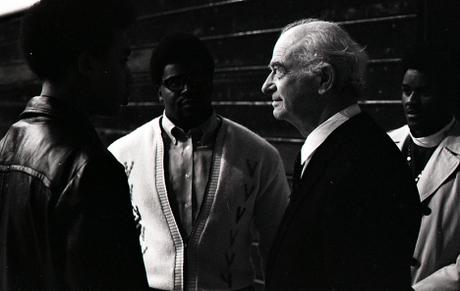

A strong supporter of individual rights, Pauling was uncertain as to why Milton could not wear a beard and later noted that he never succeeded in receiving a straight answer from the university’s administration concerning the rationale for this policy. Paulng also expressed a belief that the sentiment displayed on his alma mater’s campus mirrored trends at other universities and that, as with many other institutions, the roots of these brewing conflicts lay mostly with the administration’s inability to recognize the problem and to take measures to fix it.

In the days following the lecture sit-in, OSU President James Jensen took steps to reconcile with the BSU, but he did not meet with success. On March 1, the BSU announced the next in its series of actions to stand up for the rights of African American students at OSU. Class boycotts followed on March 4, with hundreds of students, faculty, and staff joining in support. Athletic events were also boycotted both at OSU and elsewhere, and black athletes in the PAC-8 joined the protest by refusing to participate in games against OSU.

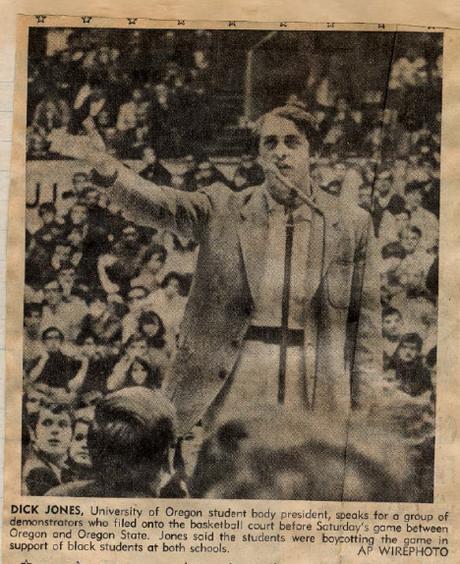

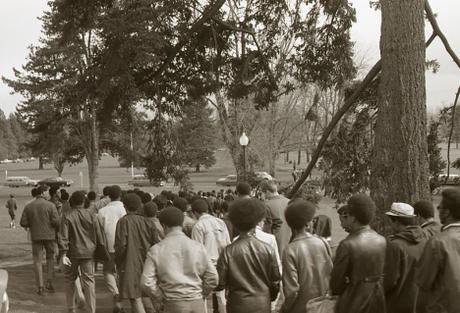

On March 5, forty-seven black students – essentially the entire African American student population at the school – marched out of the main gate on the east side of OSU’s campus. The walkout began with a rally held in the Memorial Union that included a talk delivered by BSU president Mike Smith. Speaking to a gathering of more than 1,000 faculty and students, Smith stressed that black students could no longer accept “the plantation logic” upheld by the administration and athletic department at OSU, a “hallowed institution of racism.” Reporting on these events the next day, the Scab Sheet suggested that the OSU walkout was the first of its kind at an American college or university.

The Oregon State BSU chapter was joined in the walkout by over 100 members from the University of Oregon’s Black Student Union, who chartered buses and drove up to Corvallis to participate in solidarity. There was also a rally held in sympathy at Portland State University to support the actions on OSU’s campus. The president of PSU’s Black Student Union spoke at the rally and condemned OSU’s “policy of tradition” as being “not in accord with what’s going on today.”

African American students walking off the OSU campus, March 5, 1969.

On March 6 the OSU Faculty Senate convened and passed an amended version of an “Administrative Proposal” that had been drafted by the school’s Office of Minority Affairs. This proposal included the creation of a Commission on Human Rights and Responsibilities.

The following day, three students withdrew from the university to seek education elsewhere. In response, the Faculty Senate met again to declare an emergency, an action which allowed the students who withdrew to receive an incomplete on their transcripts rather than a failing grade. Faculty members at the University of Oregon also met around this time to consider a proposal that would allow black students from OSU to be admitted as expediently as possible, should they choose to pursue their education at the university.

In an editorial, the Scab Sheet expressed a lack of surprise that the black students had left. After all,

Arrayed against them was a coalition of the University administration, the Athletic Department, the various athletic supporters, white athletes, Chamber of Commerce and alumni.

Furthermore, the university had earned a reputation for being ill-prepared to deal with minority students, and had compiled a record of inaction in handling problems of this sort. In fact, as explained by the president of the Associated Students of OSU, inaction seemed to be the university’s current formal policy. Indeed, one year before, the university had turned back over $100,000 in federal funds that had been earmarked for the recruitment of minority students. In the view of the Scab Sheet, the situation had deteriorated “to the point that blacks could maintain pride and self-respect only by disassociating themselves completely from Oregon State University.”

The departure of many black students from OSU’s campus in 1969 altered student demographics for many years to come and exacted lasting damage to the university’s reputation within multiple communities. With respect to athletics, Dee Andros was not able to convince a single African American player to join his 1970 recruiting class, and from 1971 to 1998, OSU’s football teams posting losing records, still the longest run of futility in the history of Division I football.

Fred Milton, whose refusal to shave his beard brought decades of tensions to a head, ultimately transferred to Utah State University. Milton later enjoyed a successful career at IBM and Liberty Mutual Insurance, before moving into the public sector as a civil servant working for the city of Portland and Multnomah County. He passed away in 2011 at the age of 62.

Though a painful moment in OSU history, the actions taken by the BSU in winter 1969 led to direct and meaningful changes on the Corvallis campus. Later that year, OSU established the Educational Opportunities Program, which was designed to help recruit and retain students of color. Three cultural centers were also established on campus, each a mechanism for creating community spaces for students of color and a platform for sharing these students’ experience with the broader university community.