[Part 3 of 3]

As Robert Oppenheimer’s loyalty hearing before the Atomic Energy Commission moved forward, the discussion surrounding Oppenheimer’s plight escalated, both within the scientific community and beyond. Linus Pauling joined with many other scientists in coming to Oppenheimer’s defense and actively spoke out against the actions that the government was taking.

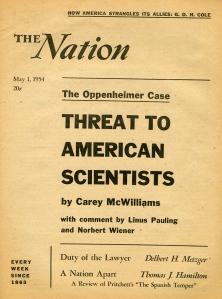

Pauling’s disgust with Oppenheimer’s treatment, combined with the on-going nuclear tests being conducted at Bikini Atoll, prompted him to pen an article that was published on May 1, 1954 in The Nation. In “A Disgraceful Act…,” Pauling argued against what he described as “atomic barbarism” and connected this issue with the need to take a stand for the freedom of the mind and the right for scientists to pursue their own work.

Pauling strongly believed that scientists bear a social responsibility that extends beyond their scientific work itself. In his work and actions, Oppenheimer certainly toed the line between being a scientist, citizen, and government employee. This role was complicated at times and was a position with which Pauling was intimately familiar.

In describing Oppenheimer in “A Disgraceful Act…,” Pauling’s broader feelings are evident:

The conclusion that Dr. Oppenheimer is a loyal and patriotic American must be reached by any sensible person who considers the facts. It must have been reached by the A.E.C., and by President Eisenhower himself. We are accordingly forced to believe that the recent action is the result of political considerations – that Dr. Oppenheimer has been sacrificed by the government to protect itself against McCarythism.

…It has been said that Dr. Oppenheimer opposed the H-bomb program at the time, 1949, when the initiation of this program was under consideration. … Dr. Oppenheimer is to be commended if he advanced moral and ethical arguments against the manufacture of that greatest of all weapons of mass destruction, the H-bomb. … Instead of raising trivial questions about Dr. Oppenheimer’s loyalty, which he has demonstrated time and time again since 1940 through his deeds, the government should be asking him to use his great intellectual ability, in collaboration with many other outstandingly able physical scientists, social scientists, and specialists on international relations and other aspects of the world problem, to find a practical alternative to the madness of atomic barbarism.

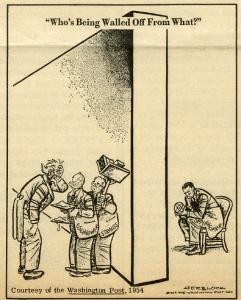

Unfortunately for Oppenheimer, the panel reviewing his case did not view him as favorably as many of his colleagues and fellow scientists did. Within the majority report, it was decided that Oppenheimer was loyal, but not completely; he had stumbled once, he could falter again. The panel also observed that Oppenheimer had shown a “serious disregard” for security requirements and evidenced “susceptibility to influence,” which could hurt national security.

These claims were paired alongside the argument that he had displayed “disturbing” conduct toward the H-bomb program and had withheld his full support of the project. He was also charged with a lack of candor during periods of the board’s hearing, particularly when discussing the extent of his opposition to the development of the hydrogen bomb.

The minority report, on the other hand, emphasized that the nation had taken

a chance on him because of his special talents and he continued to do a good job. Now when the job is done, we are asked to investigate him for practically the same derogatory information…. No one on the board doubts his loyalty…and he is certainly less of a security risk now than he was in 1947, when he was cleared. To deny him clearance now for what he was cleared for in 1947, when we must know he is less of a security risk now than he was then, seems to be hardly the procedure to be adopted in a free country.

Other statements within the report make comparisons to Oppenheimer’s handling with that evidenced in less democratic countries, like Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany. The document likewise reminds its readers that “All people are somewhat of a security risk.”

Oppenheimer appealed the AEC’s decision immediately after it was issued. In the appeal, Oppenheimer’s lawyer pointed out that the majority decision not to recommend reinstatement of Oppenheimer’s security clearance stood in “stark contrast” to the board’s findings that the scientist was loyal. In the view of the appeal, the board’s decision “raise[d] doubts about the process of reasoning by which the conclusion was arrived at.”

Oppenheimer ultimately lost his appeal on a 4 to 1 vote – a tally heavily influenced by delegates’ sense of “defects in [Oppenheimer’s] character.” The lone dissenting vote in the appeal case was cast by the only scientist on the committee, Henry D. Smyth.

Nontheless, the larger community of scientists generally supported the continued push for Oppenheimer’s clearance. In an editorial published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists after the appeal verdict was rendered, ten of Oppenheimer’s colleagues, including Harold Urey and Leo Szilard, issued a response. “It seems to us a breach of faith on the part of the Government,” they wrote, “to call upon a man to assume such heavy responsibilities in full knowledge of his life history and then, after he has demonstrably done his best and given the most valuable services to the nation, to use the facts which were known all the time to cast aspersions on his integrity.”

The Executive Committee of the Federation of American Scientists furthered this sentiment in a statement of its own:

We hope that the Atomic Energy Commissioners will again review the record and, within the bounds set by law and Executive Order, do justice to Oppenheimer as an individual. But beyond that we urge strongly that the entire machinery of security must itself come under review.

In the end, for many the case served as another example of the existence of an unwritten imperative that scientists stay in line if they were to associate with the government and maintain a public image. But for others, the trial marked a breaking point. As Pauling concluded in a letter to a friend who had complimented his Nation article, “For a couple years I have greatly restrained myself with respect to political action. I have decided that not only is it wrong to permit oneself to be stifled, but it isn’t worthwhile.”