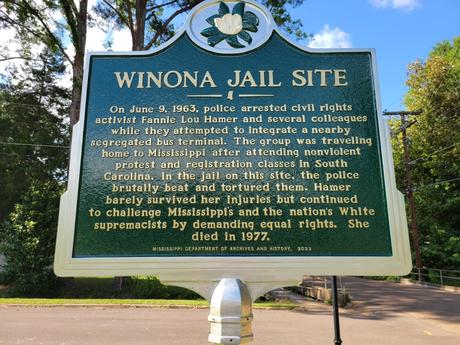

The first part of this day was dedicated to Curtis Flowers; the second half to Fannie Lou Hamer. This was by design. I came to Winona, Mississippi to spend some quality time with Curtis, and to attend the unveiling ceremony of a new plaque commemorating the day Ms. Hamer and her companions were savagely beaten in the Montgomery County Jail. The two are firmly connected, in my mind at least.

I suspect you have heard of Curtis Flowers, a man wrongfully accused of murdering four people in a Winona furniture store in 1996. Friends of Justice has been working on his behalf since 2008. On the surface, what happened to Hamer in 1963 and what happened to Flowers thirty-three years later, bear little resemblance. To begin with the most obvious difference, Hamer was a woman; Flowers is a man. Hamer was bold and assertive; Flowers is gentle and fun-loving. Hamer was the victim of violence; Flowers was falsely accused of perpetrating violence.

But the two stories follow a similar narrative arc. Both happened in Winona, Mississippi. Both were acts of violence (one literal, the other judicial) inflicted upon a helpless person of color. The beating of Hamer and the framing of Flowers were both acts of desperation.

The violence inflicted on the helpless body of Fannie Lou Hamer was a symptom of the civil rights movement unfolding in the Mississippi Delta. The state of Mississippi, in the iron grip of a proudly racist caste of white men, was winning every war and, very clearly, losing the battle. These men wanted to keep the educational and political systems of the state in white hands for the benefit of white citizens. There was no public debate. Those who disagreed kept their mouths shut or suffered the consequences. Pastors, pundits and politicians who supported the cause of civil rights were lucky if they merely lost their jobs. It could get far worse.

And yet women like Fannie Lou Hamer refused to quit. They kept holding mass meetings in Black churches. They kept teaching Black children about racial equality. Worse still, they insisted on quoting the Bible, and there was so much Bible to quote. The day after Ms. Hamer was beaten half to death, she informed the sheriff’s wife that, contrary to what she might have been told, God demands justice and racial equality. She quoted chapter and verse. The Sheriff’s wife, a good Baptist, took notes.

Fannie Lou Hamer wasn’t beaten because official Mississippi thought she could be silenced; she was beaten because everyone knew she couldn’t be silenced.

State officials were equally desperate when Curtis Flowers was arrested, albeit for a very different reason. Four innocent people had been senselessly slaughtered in a Winona place of business, and no one had the slightest idea who to blame. But this case couldn’t go cold. Somebody had to be arrested, charged and convicted.

And it was obvious to everyone associated with the investigation of the case, that the sacrificial lamb had to be poor, powerless and Black. Curtis Flowers was singled out because his name appeared on a pay check found on the desk of Bertha Tardy.

And how do you frame a powerless Black man? You find a dozen-or-so powerless Black people to testify that they saw him walking to and away from the scene of the crime. And you promise to go easy on a psychopathic repeat offender if he will only testify that Curtis Flowers admitted the crime in the course of a jailhouse conversation.

Once you have all these witnesses on the record, you threaten them with prison time if they choose to backtrack. No single witness is particularly persuasive, but, taken together, a clear portrait of guilt can be scrawled across the courtroom walls.

In both the Hamer and Flowers cases, then, the state was doing what the state had to do. And the good citizens of white Mississippi did their part. When the feds placed Sheriff Earl Wayne Patridge and his deputies on trial, they were expeditiously acquitted. When the state paraded their long string of compromised witnesses before the jury, they voted to convict and to kill.

We know what happened in the Hamer case, because she lived to tell her story. Repeatedly, and with no details omitted.

We know what happened in the Flowers case, because the witnesses recanted their testimony. Every one of them.

Curtis and I attended the Hamer unveiling together. That was as it should be.

Like I said, I spent the morning cruising Winona with Curtis and his friends. Curtis has a lot of friends. He seems to know everybody in town. Everybody loves Curtis Flowers, and he loves them right back. On the advice of his attorneys, he spent the first six months of his freedom living with his sister in Plano, Texas. But he couldn’t stay away from Winona forever. As he drove around town, showing me his favorite fishing holes and other local landmarks, his love for the community was evident. His ambition (inherited from his mother, Lola) is to buy up all the abandoned homes in town, fix them up, and rent them out. He can’t do it, of course; but he would if he could.

A day in pictures:

When the Hamer event concluded, and the crowd of 300 started drifting away, I hung around and visited with whoever wanted to talk to me. I was invited to a dinner at the Catholic Church next door and seated, to my delight, next to Euvester Simpson, the woman who, at the tender age of seventeen, cared for Fannie Lou when the guards had done their worst. “We just sang songs all night,” she told me. “What else were we supposed to do? We had to look beyond ourselves.”

We still do!

- A day of reckoning in Winona, Mississippi: Why Fannie Lou Hamer and Curtis Flowers are forever united in a corner of my mind

- Returning to the scene of the crime

- The Science of False Confessions

- What Jonathan Haidt and Yascha Mounk get wrong about the culture war

- Conservatives say no to the human rights revolution

Email Address:

One-TimeMonthlyYearly

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

$5.00$15.00$100.00$5.00$15.00$100.00$5.00$15.00$100.00Or enter a custom amount

$Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly