By Alan Bean

By Alan Bean

The Common Peace Community was inaugurated on Saturday, March 23rd at Broadway Baptist Church with thirty-five wonderful people in attendance. As participants entered the Good Shepherd Room, Al Travis, Broadway’s gifted organist, played softly in the background. After we all had our food and were gathered around the tables, we talked about why we had come and what we were hoping to see. The Rev. Sue Turner gave an eloquent invocation and then it was my turn to explain what a Common Peace Community is all about. Here’s what I said:

Exactly 100 years ago, Robert Frost spent the day with his neighbor, rebuilding the rock wall that separated their properties. His companion kept spouting the ancient adage, “Good walls make good neighbors.”

Frost didn’t agree.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

what I was walling in or walling out,

and to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

that wants it down.

Maybe Frost had been reading Ephesians 3 where the Apostle Paul picks through the rubble of the wall that once separated Jew from Gentile. “The wall is down,” he cries in triumph. Jesus knocked it down. He is our peace, our common peace, having broken down the dividing wall, that is, the hostility between us.

The wall separating Jews and Gentiles was old and stout, but it wasn’t the only barrier frustrating a common peace. Paul told the church in Galatia:

For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ,

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.

The civil rights movement applied that same gospel logic to the Jim Crow wall that separated (and continues to separate) black Christians from white Christians. Jesus demolished that wall as well.

If Jesus Christ is to be our common peace, the walls must come down. There is something in the heart of God that doesn’t love a wall; that wants it down. That knocks it down. That wants to use you and me as the battering ram.

Good walls may make good neighbors, but they are anathema to the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Jesus spent most of his ministry hammering away at the oldest, stoutest barrier of them all: the wall dividing the poor from the prosperous. This is the organizing theme of the Gospels: the unrighteous poor flock to Jesus while the righteous wealthy plot his downfall.

We cannot see God clearly until the walls come down. None of us can experience the glory of the gospel until all of us are one in Christ Jesus.

We are here to knock down walls. We are here to build a Common Peace Community.

That’s the basic idea. But what does it mean in practice?

After a lovely Taize-style hymn from an impromptu choir organized by Tiffancy McClain, Hope and Nazry Mustakim came to the front. Nazry told us about coming to America as a boy from Singapore, growing up as the only non-white kid in the class, getting into the wrong crowd, drinking and doing drugs and, finally, taking a plea bargain. Then he told us about turning his life around, becoming a dedicated Christian, getting married to Hope, buying a home and settling down. Then came the knock on the door.

Nazry had a green card, but Hope wanted to sponsor him for citizenship. That’s when the plea bargain popped up and Nazry was classified as the kind of person the US government wanted to deport.

Hope described the nightmarish spectacle of seeing a swat team, replete with flak jackets, standing in her bedroom. She talked about waking up certain that Nazry must be dead. She described the long, agonizing quest for justice: organizing, researching, reaching out to immigration attorneys, and finally, after ten dreadful months, her reunion with Nazry.

T hen Nazry told us about the people he met in the Pearsall Detention Unit in South Texas. The men who re-entered the country after being deported because they couldn’t stand to be separated from their young children. The families that had been ripped apart by decisions made by invisible bureaucrats who never had to witness the chaos they were creating. Nazry told us that, after listening to these stories, he couldn’t return to the free world and go back to his old life. He knew too much. He was a man with an obligation to the truth.

hen Nazry told us about the people he met in the Pearsall Detention Unit in South Texas. The men who re-entered the country after being deported because they couldn’t stand to be separated from their young children. The families that had been ripped apart by decisions made by invisible bureaucrats who never had to witness the chaos they were creating. Nazry told us that, after listening to these stories, he couldn’t return to the free world and go back to his old life. He knew too much. He was a man with an obligation to the truth.

I wish you could have been there. Watching the adoring glances that passed between Hope and Nazry was a testament to the sheer tenacity of love: their love for Jesus Christ, and their love for one another.

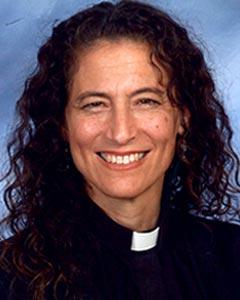

Alexia Salvatierra

Then it was time for Alexia Salvatierra to tell us about the compassion of Jesus. In Luke 9, she said, Jesus “went about all the cities and villages, teaching in their synagogues and preaching the gospel of the kingdom, and healing every disease and every infirmity. When he saw the crowds, he had compassion for them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd.”

To have compassion, Alexia told us, is to suffer-with, to feel the pain that surrounds us as if it were our own. Then she told us about the I Was a Stranger Challenge which is based on the final words of Jesus’ teaching ministry,

Come, O blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you clothed me, I was sick and you visited me, I was in prison and you came to me.

No one has worked harder creating the Evangelical Immigration Table than Alexia Salvatierra. A wide range of American evangelical churches and organizations came together last year behind the need for compassionate immigration reform. There is only one woman in this picture, and without Alexia the table wouldn’t have come together.

No one has worked harder creating the Evangelical Immigration Table than Alexia Salvatierra. A wide range of American evangelical churches and organizations came together last year behind the need for compassionate immigration reform. There is only one woman in this picture, and without Alexia the table wouldn’t have come together.

Each participant was given a bookmark containing forty passages of scripture that witness to God’s love for the stranger and the alien. You take the challenge by agreeing to read one passage a day for forty days. Then, you are encouraged to take the book mark to a legislator who will vote on state or national immigration legislation and ask that person to take the challenge.

David Grebel

The Common Peace Community also celebrates and strengthens ministries of compassion that have been in existence for a long time. On Saturday, David Grebel, a college administrator and ordained minister, told us how his involvement in Broadway Baptists’ Agape meal has changed his life. We minister to the poor and the homeless, David said, but they also minister to us. When David preaches on Thursday nights people listen. They listen because David has won their respect by respecting the integrity of their lives. The walls separating the righteous wealthy from the unrighteous poor come down on Thursday nights.

Several people have told me that the 90-minute gathering has transformed the way they think and feel. It’s one thing to have a do-gooder like me drone away about this stuff; it’s something entirely different to listen to those who have felt the sting of a broken system.

The service ended with my daughter Lydia and I singing a song that came to me a couple of weeks ago while I was running with the dog.

A common peace community starts when we look at the world.

A common peace community starts when we look at the world

Through the eyes of the poor And asks why they continue to be,

Why is it you and not me? Why is it so hard to see through the eyes of the poor?A common peace community shines in the night of the world

A common peace community shines through the night of the world

In the eyes of the poor.

And asks why do we feel so alone?

Why are we chilled to the bone?

How can we find our way home through the eyes of the poor?A common peace community grows as we pray for the world

A common peace community grows as we pray for the world

Through the eyes of the poor.

Saying, “Lord, let thy good kingdom come,

Lord, let thy good will be done,

Lord, let us see thy good Son in the eyes of the poor.