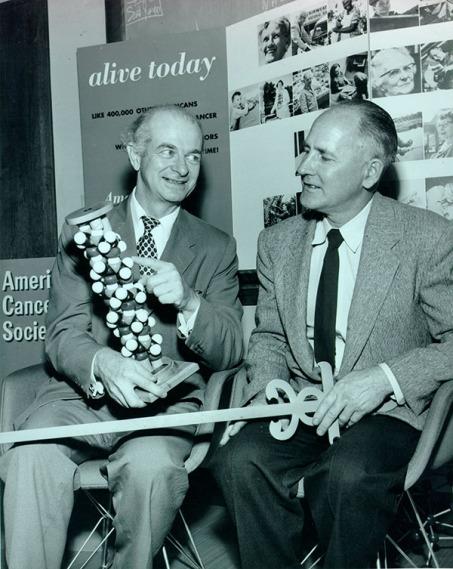

Linus Pauling, unidentified [Norman Church?] and George Beadle participating in what is believed to be a groundbreaking ceremony for the Church Laboratory, circa 1955

Linus Pauling, unidentified [Norman Church?] and George Beadle participating in what is believed to be a groundbreaking ceremony for the Church Laboratory, circa 1955[Pauling as Administrator]

Though pressures related to his political activism began to pose more and more problems for Linus Pauling, he was largely able to maintain effectiveness in his position as Chairman of the Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering at the California Institute of Technology. Notably, in the midst of all the controversy, he was able to keep on track the planning for a new biochemical laboratory to be built on campus.

Plans for the new facility began to take shape in 1952, following a three-year fundraising effort. And as the architects started to work out the specifics of the new building, each research group within the division began to stake their claims to the amount of space they thought they needed.

Chief among these claimants was Pauling himself. With Dan Campbell, Pauling put in for 15,000 feet to be used by the immunochemistry group. A separate request for 12,000 square feet was also put forth by Pauling, joined this time by Robert Corey and the x-ray diffraction group. Both requests were double the space allocated to these activities in in the Crellin Lab. In addition, Pauling wanted an increase in his personal office and laboratory space, bumping up from 1,000 to 1,500 square feet. By comparison, Carl Niemann’s enzyme group was to receive 4,500 square feet and the analytical chemistry group would get 3,000.

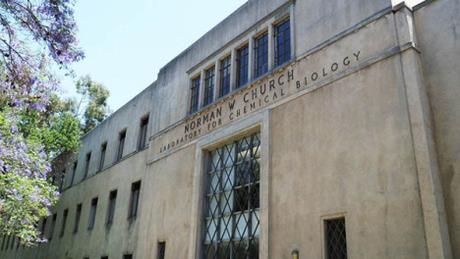

At the end of August 1952, fundraising for the new building received a big boost when Caltech accepted $750,000 from a local businessman, Norman W. Church. The gift was large enough to pay for the shell of a 70,000 square foot biochemical laboratory, though not enough to connect the new laboratory to Crellin, as was the ambition. (Caltech thought that it could potentially cover the cost of doing so itself.) Estimates to complete the entire building ran to $1,400,000, with another $270,000 anticipated for furnishings. By the next May, as the Institute began accepting construction bids, those estimates rose to around $2 million to complete the main wing.

As the project advanced, it became clear that the funds on hand were not sufficient. In August 1953, J. Holmes Sturdivant, who was supervising the Biology component of the project, conveyed to Pauling the bad news that the project was short to the tune of $500,000. To make amends, Sturdivant felt it likely that the design would have to scrap two planned basements and not furnish the building as originally conceived.

Pauling appointed a committee to address this matter, and the committee concluded that the two basements were crucial to the project because the new facility would be too small to function effectively otherwise. The group further suggested that it was fine to keep portions of the building unfurnished at the outset — the basement was the priority. Pauling agreed, telling Caltech President Lee DuBridge that they could always raise more money to fully furnish the space later on.

Not merely interested in the internal layout of the new biochemical laboratory, Pauling also wanted to make a stylistic imprint on the building’s exterior. In his visits to England and France four years prior, Pauling toured many eleventh and twelfth century Norman churches and was impressed by the elaborate receding arched doorways – many of them decorated with depictions of spirits – that adorned these houses of worship.

Since the new Caltech building would be called the Norman W. Church Laboratory, Pauling thought it appropriate to similarly decorate its main entrance using depictions of bacterial cells, viruses, animals, molecular crystals, and scientific instruments. In the end though, this idea did not come to pass. Whether it was from lack of interest or lack of funds, the final building boasted a much less ornate entryway.

In 1952, Warren Weaver, Director of Natural Sciences at the Rockefeller Foundation, informed George Beadle, who was the chair of Caltech’s Biology division, that the foundation planned to reduce its support for biological projects due to an increasing number of alternative funding sources that were becoming available. That said, Caltech would still be at the top of the foundation’s list for research funding requests of “a more general nature.”

Knowing full well that the Institute was nearing the end of a seven-year $700,000 Rockefeller grant covering biochemical research, Weaver told Beadle of the potential for a new $1 million allocation that could fund ten to twenty years of biochemistry research with additional money allocated for equipment. In his communications with DuBridge and Pauling, Beadle emphasized that “Weaver made it quite clear without saying so directly that we would not be left high and dry.”

That Weaver had communicated this possibility to Beadle rather than Pauling was perhaps a sign of Pauling’s decreasing involvement in higher levels of active leadership at Caltech since the end of the Second World War. But while he no longer appeared to take the lead, Pauling did maintain an important role in securing funding as head of his division. And as he worked to generate funds to broaden the divisions horizons, he continued to cling to the original post-war vision for biochemical medical research at Caltech that he had first formulated eight years earlier, a vision that had thus far received relatively minimal financial support.

In making their formal appeal to the Rockefeller Foundation for further funding, Pauling and Beadle first laid out the extant funding sources that were currently supporting their two divisions. They began by noting that the Institute itself provided $325,000 per year for chemistry and $250,000 for biology. Another $600,000 in soft money was also on hand, including $100,000 per budget cycle from the current Rockefeller grant. Finally, an additional $300,000 was channeled annually to the two units from endowment funds.

Some of those endowments came from individuals who had willed their estates to the Institute. In May 1952, Pauling wrote to Caltech trustee George E. Farrand to express his gratitude to a Mrs. Robinson who had left “the bulk of her estate” to Caltech for cancer research. In his note, Pauling touted the Institute as being the perfect place to conduct fundamental research that might supplement clinical trials going on elsewhere. But he hastened to add that these kinds of donations were not enough to sustain the levels of medical research that he and his colleagues thought possible.

As Pauling and Beadle crafted their pitch to the Rockefeller Foundation, they stressed that future support needed to be long-term – at least fifteen to twenty years – if they were going to attract tenured faculty capable of conducting world class research. Covering a time span of this length would require around $3 million and the duo requested that the foundation commit to providing half this total, with the other half to be raised by the Institute from other sources. With funding at this level on hand, and with endowment interest accruing, the two divisions would be able to spend, at most, $150,000 a year for a minimum of fourteen years.

Happily, the foundation agreed to Pauling and Beadle’s proposal, with the proviso that the Institute generate the matching funds within the next three years. This major commitment from a key external partner appeared to finally secure Pauling’s postwar plan for long-term biochemical research at Caltech.