Donald Watkins (center) and his children

A Black man from Alabama, with a career of almost 50 years in the legal profession, advises his grandchildren on July 4, 2023, not to place their hopes on the "affirmative action" that can be taken away by a scandal-plagued U.S. Supreme Court. Instead, Donald Watkins encourages the upcoming generation to pursue a different kind of "affirmative action," the kind exemplified by the extraordinary achievers in their family tree. In an open letter published today at his Web site, Donald Watkins reminds his grandchildren to look to their forebears for "affirmative action" that has a powerful and lasting impact -- the kind no one can take away from them. Writes Watkins:

Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court banned affirmative action for black students in college and university admissions programs.

Affirmative action for marginally qualified white students who are admitted into these colleges and universities under legacy admissions programs was left intact.

Do not despair. As a family, we have never depended on the fickle generosity of third parties, or the lowering of performance standards, or the political machinations of a machete-wielding Supreme Court.

The Watkins bloodline has always stressed educational excellence, brainpower, goal setting, focus, perseverance, patience, financial independence, and hard work to secure and protect our future in American society. These are the only tools that have consistently worked in the face of never-ending impediments to our inclusion in the socioeconomic progress of this nation.

Our family mantra is simple. Once a Watkins student enters any classroom, first place is taken by him/her. We will outthink, outwork, outperform, and outlast any competitor or adversary.

The Watkins family does not complain whenever we are cheated out of victories that rightfully belong to us, or whenever we are "railroaded" in contests by biased officials. These situations occur often in life. You can count on them like you can count on bad weather.

We use cheating, railroading, and racial discrimination as fuel for our passion and mission in life.

Where can the upcoming generation turn for inspiration? Watkins provides a roadmap:

By studying the family values that my paternal grandparents, John Adam and Sallie Emma Watkins, instilled in their children and grandchildren, you will see the tangible results that flow from the Watkins brand of “affirmative action."

Adam and Sallie Watkins

My lessons on manhood came early. John Adam Watkins, whom we called Adam Watkins, taught me what he imparted to his sons – “God made you a man, so be a man.” There is nothing ambiguous about who we are or what we stand for.

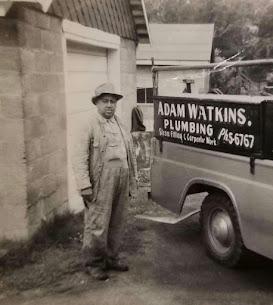

Adam and Sallie Watkins lived in Clarksville, Tennessee in the 1950s. Adam Watkins gave me my first summer job – a plumber’s apprentice -- and my first paychecks. He ran the biggest plumbing company in town. Granddaddy Watkins had mostly white customers, and he lived on Main Street. Adam Watkins taught me that the ability to render a first-class, high-quality business service transcended race.

Adam Watkins

Sallie Emma Watkins handled the company's money and kept its financial books and records. She was strong, smart, and kind. She was Adam's' life partner in every way.

In 1962, I also watched the Tennessee Democratic gubernatorial candidate Frank Clement come to granddaddy Watkins’ home and request his political support at a time when only a small number of blacks in the state had the courage to register and vote in Tennessee elections prior to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Adam and Sallie Watkins, who were born in 1890 and 1896, respectively, feared no man and were respected by all men and women.

The next stop on the family roadmap includes a fruitful chapter in Alabama:

Dr. Levi Watkins, Sr.

Dr. Levi Watkins, Sr., was the oldest of Adam and Sallie Watkins’ five sons and two daughters. He was also my father. He was the strongest and smartest man I have ever known.

When my father was a child, he was not allowed to attend the “white” school in his small Kentucky community. He walked alone to the “colored” school in Cadiz, which was six miles away. Father passed the local “white” school twice each day. Sometimes, he was wet and cold. And sometimes, his feet were numb from walking in the snow and sleet of winter. To attend school, my father had no choice. He grew to hate racism, but not the innocent children in the “white” school he passed each day.

Adam and Sallie Watkins taught my father how to be morally strong, how to be fair, and how to be concerned about the plight of African-Americans in the segregated South.

Dr. Levi Watkins served as president of Alabama State University from 1962 to 1981. He took a small, neglected, all-black state college in Montgomery, Alabama, from an unaccredited status in 1962 to full accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools in 1966. It was the second time my father had accomplished this feat in a four-year period. The first time occurred in the 1950s when father served as president of Owen Junior College in Memphis, Tennessee.

Lillian Bernice Varnado Watkins was my father's wife, best friend, spiritual leader, my role model for a woman, and personal hero. Together, they taught me how to be a strong man, how to respect women, how to deal effectively with bullies and bigots, and how to stand up for what is right, even when I had to stand by myself.

As was the case with Adam and Sallie Watkins, my father and mother groomed each one of their three daughters and three sons to become loving and caring community leaders. They loved to inspire, motivate, educate, and support the younger generations. To them, education excellence was the surest pathway to a better life. But, the pursuit of this excellence must start in K-12 schools.

The Watkins family name wound up making a major imprint on the world of medicine:

Dr. Levi Watkins, Jr.

On May 29, 1966, The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee) published an article announcing the acceptance of the “first Negro ever accepted by Vanderbilt University’s School of Medicine.”

His name was Levi Watkins, Jr. He was my oldest brother.

Even though Levi was accepted at other prestigious medical schools around the nation, he was denied admission to The University of Alabama’s medical school in Birmingham in 1966.

Levi’s experience at Vanderbilt was challenging. While he mastered the academic course of study with ease, Levi caught pure hell from fellow students who resented his presence at the medical school.

Levi’s worst experience came when he exited his dormitory one day, and someone emptied a full can of garbage on him from a second-floor window. He returned to his room, quickly cleaned himself up, and hurried to class. Nothing these students did to Levi ever broke his spirit or focus on graduating with honors.

After graduation, Levi began his medical residency at Johns Hopkins Hospital. There, he became chief resident of cardiac surgery, acting as the first African American chief resident at the university. Levi eventually would become a world-famous heart surgeon and associate dean at Johns Hopkins Medical School.

In 1975, Levi continued the pioneering medical research on the implantable defibrillator that had been started by Drs. Michel Mirowski, Morton Mower, and William Staewen. In February 1980, Levi implanted the first defibrillator at a time when many white Johns Hopkins University Hospital cardiac patients did not want a black heart surgeon, who had been nominated for the Nobel Prize in Medicine, to perform life-saving surgery on them. Levi overlooked their bigotry, loved them as human beings, and saved their lives anyway.

More than 3 million people worldwide are walking around with implantable defibrillators that were developed by the pioneering medical research of Drs. Michel Mirowski, Morton Mower, William Staewen, and Levi Watkins, Jr. The device, which detects arrhythmias in the heart and emits an electric charge to correct them, prevents sudden death from an irregular heartbeat.

Levi’s motto in life was this simple phrase: “Let your work speak for you .... and you’ll never have to say anything about yourself.”

Levi's journey from "VU Med School Get's 1st Negro" to the dedication of The Levi Watkins, Jr. M.D. Outpatient Center at Johns Hopkins Medical Center on June 8, 2023, has been an amazing experience for our family.