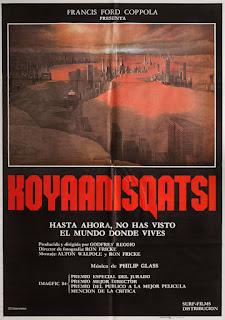

In the Hopi language, Koyaanisqatsi means “life of moral corruption and turmoil”, or “life out of balance”. Director Godfrey Reggio’s 1982 non-narrative movie of the same name offers up images of the world as it existed at that time. Nature collides with cityscapes; humanity collides with technology. Aided by the excellent cinematography of Ron Fricke (who would himself dabble in non-narrative with Chronos, Baraka, and Samsara) and the otherworldly music of Philip Glass, Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi is equal parts beautiful and disturbing, moving and frightening.

Shot mostly – but not entirely – with time lapse photography, Koyaanisqatsi opens with the serenity of the natural world: Canyonlands National Park in Utah. From there, we’re treated to cloud formations, a waterfall, and other such images, which are abruptly, violently disturbed by footage of nuclear tests in the desert, the mammoth mushroom clouds filling the screen, and signaling our entry to the world of progress.

Sunbathers gather on a beach next to a nuclear generating station. Traffic moves quickly along the streets of Los Angeles and New York. Hundreds of tanks gather on the shoreline of an unknown country. There is plenty of urban decay as well, with the implosion of several dilapidated buildings.

Microchip manufacturing and assembly lines are interspersed with malls and shopping centers. Professionals as well as the homeless are given equal screen time. It all culminates with a rocket that explodes soon after its launch, the camera following the burning debris as it falls to earth.

The images come fast and furious throughout Koyaanisqatsi, and there is no dialogue, no narration of any kind. It is a movie defined by its visuals. But what does it all mean? Is it, as its title suggest, a depiction of “life out of balance”, or simply an exploration of the modern world?

When speaking of Koyaanisqatsi and its sequels (Powaqqatsi in 1988 and 2002’s Naqoyqatsi), director Reggio said “These films are meant to provoke. They are meant to offer an experience rather than an idea, or information, or a story about a knowable or fictional subject”, adding it was up to the viewer to determine what it means to them.

So what does Koyaanisqatsi mean to me?

Well, this was my second viewing of the movie, and I’ve had very different reactions each time. The first was about 15 years ago, and while I admired the film, it did not penetrate my mind or my emotions. It left me cold.

Watching it again now, the images, the music, the conflict of the natural and modern world, resonated with me. I was engrossed in Koyaanisqatsi, and when it was over, I came away feeling life truly was out of balance, perhaps even more so now than in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s (Reggio and Fricke started shooting the movie in 1975).

Koyaanisqatsi gave me plenty to think about, and I will likely continue turning it over in my mind for days to come. What was initially an empty experience has become something I will not forget.

Rating: 9 out of 10