Like his good friend Andrei Tarkovsky (Andrei Rublev, Solaris), filmmaker Sergei Parajanov often thumbed his nose at the restrictions imposed upon artists by the Soviet regime, which insisted that all art (movies included) adhere to the principles of socialist realism, i.e. – a depiction of Communist values (united workers, etc.). Yet while Parajanov’s approach to cinema may have rubbed a few bureaucrats the wrong way (he was arrested in 1973 and sentenced to five years hard labor), there is no denying he was a true artist, a talent whose singular vision often found its way into his best works.

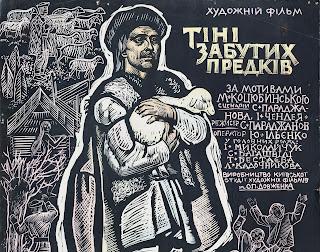

Parajanov’s most notable film, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, broke socialist boundaries in every way imaginable: story, theme, execution, and style, and in so doing became one of the most important motion pictures of the 1960s.

Set in a small Hutsul village in Ukraine’s Carpathian Mountains, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors tells the story of Ivan (Ivan Mykolaichuk). As a young boy, Ivan witnessed the murder of his father Petrik (Aleksandr Gai), who was beaten to death by Onufry (Aleksandr Raydanov), who Petrik had insulted. Despite the bad blood between their families, Ivan would eventually fall in love with Onufry’s daughter Marichka (Larisa Kadochnikova), whose feelings for him ran just as deep.

To earn money so he could marry Marichka, Ivan leaves their village to seek employment. While he was away, Marichka accidentally drowned trying to save a lost lamb.

Though heartbroken, Ivan would eventually fall in love with Palagna (Tatyana Bestayeva). The two marry, but over time Ivan becomes distant, unable to forget his love for Marichka, and it isn’t long before Palagna is having an affair with Yurko (Spartak Bagashvili).

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors stood apart from most by being one of the few Soviet-era films in which the characters spoke Ukrainian instead of Russian. Yet this 1965 movie would also distinguish itself in ways beyond the spoken word. Turning his back on the Soviet socialist realism mandate, Parajanov relied heavily on symbolism, both religious and cultural, throughout the movie; we are treated to traditional weddings, funerals, and holiday celebrations, complete with all their customs. There is plenty of folklore as well, mostly religious in nature. Lambs are a recurring theme throughout the movie, and a dream sequence centers almost entirely on the cross of Jesus. There’s even a chapter titled “Sorcery” that delves into the supernatural.

Parajanov infuses the film with style to spare. As Petrik faces off against Onufry, the camera swings around to a POV shot, so that we are suddenly seeing the action through Petrik’s eyes. When Onufry strikes Petrik, blood flows across the screen. The scenes where Ivan is in mourning for Marichka are shot in black and white, to convey his mood, only to be replaced by color once again when he meets Palagna. There is music as well, including a late sequence in which Ivan sings a duet with the spirit of Marichka.

By continually blurring the line between reality and fantasy, and doing so with such artistry, Parajanov did more than turn his back on Soviet restrictions; he took the art of film in unique, exciting new directions. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors stands alongside Battleship Potemkin, Andrei Rublev, and Come and See as one of the greatest movies to emerge from Soviet Russia.

Rating: 10 out of 10