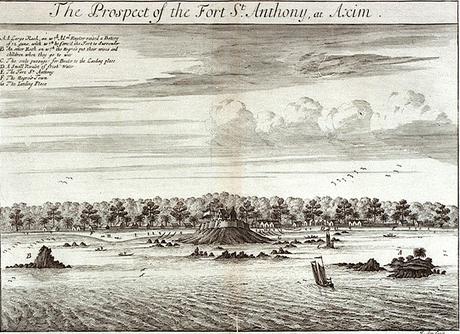

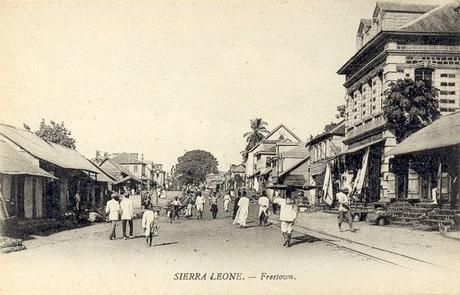

Gladys Casely-Hayford – poet, musician, dramatist, painter and storyteller - was born in Axim, the Gold Coast (now Ghana) in 1904 and died there in 1950, though she spent most of her life in Freetown, Sierra Leone.

I found the most fascinating account of Gladys Casely-Hayford's life in the book, African Treasure by Yema Lucilda Hunter. It begins with her family background and earlier years. The book goes as far back as Gladys’ great grand father William Smith Sr – an Englishman who first came to West Africa as a young man working for the Royal African Company. It also includes quite a bit on her mother – Sierra Leonean activist, feminist and writer Adelaide Casely-Hayford described as ‘outstanding amongst’ the creole élite:

... her name often appeared in the local papers in connection with the school she founded, or with her articles and speeches on social matters, including the education of African girls and Christian marriage. Excerpts from her memoirs were published in the now defunct West African Review in the early 1950s, and she also published two short stories of which the better known 'Mista Courifer' appeared in a well known American anthology.Gladys Casely-Hayford's father, as the book goes on to explain was

... the Honourable Joseph Ephraim Casely Hayford, of the Gold Coast, a member of the colony’s Legislative Council, a political activist philosopher, nationalist and pan-Africanist, successful barrister, journalist, newspaper editor and one of the first black Africans to write a novel in English.

The Prospect of Fort St Anthony, at Axim [Gold Coast]

In a short article written by Adelaide Casely-Hayford, we find out a little more about Gladys’ life: she was ‘a voracious little reader’, at fifteen ‘had written a poem …. which was the finest ever written by a Penrhos (college) girl’. Had an ‘outstanding capacity for love and kindness…. everlastingly seeking for people's good qualities rather than condemning them’, but was ‘in a chronic state of financial embarrassment’ due to marriage to a man her mother had never seen and who was never able to support Gladys and her son. By the way, that 'finest ever written' poem - was called Ears, and was included in African Treasure:When God made the world and all therein, In a sad moment of great wistfulness And loneliness, He fashioned Him a man.

"That he may cling," God said - and shaped his hands,

"That he may laugh," God said - and made his mouth,

Then paused debating, whether vision given Would make the creature infinitely wise:

"That he may see, God said - and shaped his eyes; "That he may follow Me, until I choose that we shall meet,"

God said - and gave the creature feet.

The finished creature, now with life imbued,

On the world's threshold palpitating stood; Whilst suns, stars, worlds, and moons about him whirled

The full creation, pulsing still being hurled Into position by God's mighty Hand;

The cooling sea revolving the hot land.

Man started forward. "Turn to me," God cried; But man, who heard not, could not turn aside,

Walked swiftly into life, bereft of fears, God caught him back, and laughing Made him ears.

From the heart of conscience, The path of silence, The thunder of chaos, The cycle of years, The mystery of angels, The devil's shadow, God made the ears, Then laughing at this modeled piece of grace Shaped question-wise and wondering what use Mortals would make of them, He kissed the ears in place.

The article also reveals that Gladys ‘could sit down and in a short time, write a poem which was a joy and inspiration to read’ and received an invitation to Columbia University after her mother posted samples of her work to the university. However, Gladys never made it to America:

... because of financial difficulties. As usual, her lack of discrimination prompted her to join a coloured jazz troupe with headquarters in Berlin. She bitterly regretted her decision in after years.As noted in African Treasure, during Gladys time in Berlin she worked on a detective novel set in Freetown and another book about the 'colour problem' called Shadowed Livery - none of these manuscripts have been traced.

As her mother goes on to write in the article:

Meanwhile, her considerable literary talents continued to develop by leaps and bounds. She expressed herself chiefly in poems. Knowing that Cambridge, a suburb of Boston, was the supreme educational centre of the States as it sheltered Harvard University, with its Female section, Radcliffe College, I took some of her poems to a friend there. She was so impressed that she sent them to the editor of the 'Atlanta Monthly'. To our great surprise, three of them were accepted and immediately appeared in this very literary American publication. Their appearance resulted in an offer for Gladys to enter Radcliffe College at once, but through my dear daughter's own action, another splendid opportunity was lost.

African Treasure mentions the three of Gladys’ poems selected for publication in the Atlantic Monthly were Nativity, The Serving Girl, and The Souls of Black and White. A few years after her publication in the Atlantic, three more of Gladys poems appeared in another American periodical – Opportunity, a Journal of Negro Life. The book also presents one of Gladys’ earliest poems, which she wrote the age of twelve or thirteen.

Eustace Palmer, in a chapter on Sierra Leone and the Gambia writes that:

Gladys Casely-Hayford – although she was educated, like her mother, largely in the British tradition, and was a member of the privileged creole élite, her work is noteworthy for its demonstration of the beauty and dignity of the black race. Some of her English poems appeared under the pen-name Acquah Laluah in African and American journals from the thirties on; yet they had never been collected and did not gain any sort of fame until they were included, more than ten years after her death, in several anthologies of the sixties. One of her best known is Rejoice in which she calls rousingly to her fellow Africans to rejoice in their blackness … perhaps her most remarkable poem from the point of view of African consciousness is Nativity, which is about the birth of Christ. The author sets the Christmas story in a purely African setting: the babe himself is a black child born in a native hut to a black mother and father, he is wrapped in blue lappah and laid on his father’s ‘deerskin’ hide.

Gladys also has a unique distinction of being perhaps the first Sierra Leonean to write poetry in Krio. Many of these poems are not only charming and meaningful, but also demonstrate a remarkable artistic control. It is another index of her determination, in spite of her British-type upbringing and education, to identify with Africa.

From my reading's, Gladys was said to be in the UK at least until 1924, and returned to West Africa – this time the Gold Coast - where she becomes a journalist for a weekly newspaper – the Gold Coast Leader – which her father cofounded in 1903. At least two of her poems were also published in the newspaper. One of the poems is Rejoice discussed earlier:

Rejoice and shout with laughter Throw all your burdens down, If God has been so gracious As to make you black or brown

For you a great nation, A people of great birth For where would you spring the flowers If God took away the earth? Rejoice and shout with Laughter,

Throw all your burdens down Yours is a glorious heritage If you are black, or brown.

Gladys returns to Freetown in 1926, but according to African Treasure continued to be associated with the Gold Coast Leader until 1928, as

... she reports on the proceedings of the 2nd Achimota Conference of the Congress of British West Africa in the issue of July 14, 1927, writes book reviews in the issues of August 2 1927 and September 19 1928, and publishes a poem dedicated to the late Dr. Aggrey in the issue of October 21, 1928.

On return to Freetown, Gladys taught African Folklore and Literature at her her mother's Girls' Vocational School - Industrial Technical and Training School (ITTS).

Her mother also obtained Gladys admission to Radcliffe College, which she declined, and then Ruskin College in Oxford, which she accepted. Gladys Casely-Hayford's poetic talents were admired at Ruskin, but the stress of her failed affair and her difficult relationship with her mother brought a mental breakdown in 1932. Gladys was hospitalized in Oxford. When Adelaide appeared at her bedside, a doctor advised them to have a less competitive relationship. They returned to Freetown. Gladys resumed teaching at ITTS but increasingly withdrew from Adelaide, first moving to Accra, where her father's family lived, then marrying Arthur Hunter, whom her mother had not met. Hunter was, in turn, sweet natured, abusive and adulterous. Adelaide paid for him to go to England to learn the printing business. On his return, he eschewed work as a printer. Gladys' son Kobina Hunter was born in 1940. From age ten on, he would live alternately with his grandmother or his half-uncle.

Gladys Casely-Hayford passed away in 1950, and in her lifetime wrote about subjects such s women freedom, pride, erotic love between women. Her only collection, Take’um so, was published in 1948. Gladys was also an accomplished musician who not only played the piano exceptionally, but also composed many songs and dance turns - while she lived in the UK.