From Stars and Stripes

About the author: Jim Gourley is an author, journalist, and former military intelligence officer. He served in Iraq. Gourley is a guest columnist of Thomas E. Ricks’ FP blog Best Defense.

Maryland Attorney General and Democratic gubernatorial candidate Douglas Gansler committed a campaign faux pas this week when he intoned that his opponent, Lt. Governor and Iraq war veteran Anthony Brown, was not as prepared to do a “real job.” The situation is full of peculiarities. Fox News jumped all over the opportunity to support the military, and slam a Democrat at the same time, but they misconstrued Gansler’s “real job” remark to mean the job of governor when he was really talking about healthcare reform. Fox completely glossed over that aspect, because Gansler is a Democrat criticizing a Democrat for mismanagement of a healthcare rollout. Gansler also blew the matter of Brown’s military service as a campaign issue out of proportion more than Fox. So it goes with curious cases of veterans in American political campaigns.

The issue is similar to the rancor that occurred during the Arkansas senatorial campaign when Democratic incumbent Mark Pryor said that his challenger, Iraq vet and first-term congressman Tom Cotton, felt “entitled” to office because of his military record. Cotton fired back by calling Pryor a liar and saying that the federal government needs the sort of values he learned in the army. Both cases are reminiscent of John Glenn’s famous “I have held a job” retort to Howard Metzenbaum in 1974.

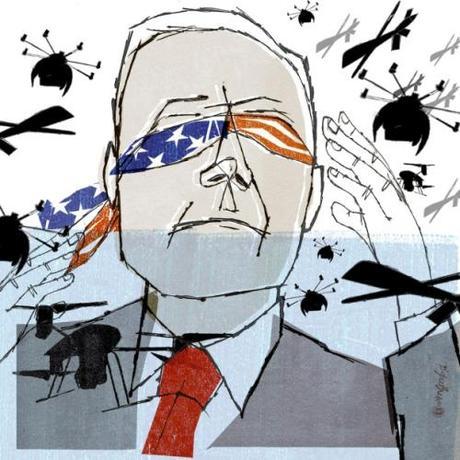

So long as veterans running for office promote their military service as a job qualification, the relative value of their service should be on the debate table. But American veterans are taking unfair advantage of the population’s newfound reverence for “our heroes.” No civilian politician can debate the merits of military service in government without becoming a pariah, and no veteran candidate will undermine their ace in the hole. So it falls to a veteran with Shermanesque interest in political office to submit, for the benefit of public discourse, the 10 most inconvenient reasons why you shouldn’t vote for a veteran.

10. We are really bad at managing tax dollars. The military’s greatest fiscal accomplishments in the last decade have been the addition of new adverbs characterizing the scale of its financial mismanagement: Institutionally, epidemically, atrociously, epically. Veteran candidates love to spout off about the level of responsibility they shouldered in the military. But unless they were a logistics or finance officer, they probably exercised very little control or supervision over accounting records. They were probably accountable for millions of dollars worth of equipment, but it’s a lot harder to lose a Humvee or a helicopter than it is subcontractor records. If you think this doesn’t come with liabilities in the civilian world, go ask the veteran executives at Wounded Warrior Project where the other 42 percent of your donation went.

9. We’re just as political as the politicians. One of the biggest messages veteran political candidates like to promote is that they want to bring “real leadership” to office instead of “politics.” This means one of three things: that the candidate doesn’t understand what leadership is, that the candidate doesn’t understand how political office works, or that the candidate understands both and is fully aware their statement is a nonsensical platitude. It didn’t even take Anthony Brown 12 hours to cleverly turn Gansler’s personal critique into “disrespect and disservice to our nation’s veterans.” The national organization dedicated to electing veterans to office also demanded an apology. Add to this a personal anecdote: I attended the U.S. Air Force Academy with New York State Senator Greg Ball, R. As a sophomore cadet, he was quite open about his desires to run for political office. The guy hated the school (not that I blame him, I did too). But he knew that a service academy class ring and a good military record would help him get into office. It doesn’t make him evil or even a bad legislator, but it does strike at the narrative that veterans run for office because some burning bush they encountered in Iraq or Afghanistan told them to.

8. Being a vet doesn’t make us a morally superior candidate. I’ve already covered this. But just for good measure, let’s take a moment to remember former Rep. Allen West, R-Fla.

7. Combat isn’t an accomplishment. “I served in Iraq/Afghanistan” is great applause-bait for campaign rallies, but people ought to scrutinize it more. Cotton and Congresswoman Tammy Duckworth, D-Ill., did go out there and faced hostile fire. That demonstrates physical courage that all Americans should and do admire. But physical courage has only relative value in the halls of Congress, which hosts an entirely different type of butchery. There have been plenty of company and battalion commanders (and more than a few generals) in combat who were incompetent. As a guy who’s been to Iraq and been shot at, I’m here to tell you it doesn’t take political acumen — or any kind of acumen, for that matter — to go to Iraq and get shot at.

6. We really don’t understand the average American. Most current serving veteran members of Congress are former army officers. They are college educated and many have graduate degrees. They began their military careers significantly higher on the pay scale than their civilian peers, never had to worry about health care, lived in the ultimate gated community, bought their groceries at federally subsidized stores, got all kinds of discounts when living on the civilian economy, were often given a pass on state income and sales taxes, and their pay raises and career advancement were more or less set to a stopwatch. Maybe being in the military is a real job, but it sure isn’t like any other job in the world, and for a lot more reasons than “the sacrifices” for which it calls. Don’t assume that fighting for you on a battlefield means this person knows how to do it in a legislative body.

5. Our life experience is limited. Veterans have worked in some challenging conditions and done some great things. But they’ve also been uniquely equipped for success. Multiple studies have cited that only about 20 percent of Americans are eligible for military service. That’s the demographic veteran candidates have worked with. Also keep in mind that, as officers, they are the top 1 percent of that 20 percent. They have never been in a job environment that routinely demanded them to build consensus, make compromises or negotiate plans. It’s an extremely hierarchal organization where everyone’s job and authority exist in a crystalline lattice, units rarely have to worry about budgets, and the preferred method of getting people to do your will is punitive coercion. In other words, it’s everything the government is not. (I disagree with this wholeheartedly. What do you think taxes are? Charity?)

4. We’re overrepresented as it is. The current Congress has 88 veterans in the House and 18 in the Senate. That’s a representation of 16 and 36 percent, respectively. Estimates put veterans between 7-12 percent of the total U.S. population.

3. We make a mess of the dialog. The Gansler/Brown controversy isn’t the only kerfuffle over veteran political candidates in recent memory. Remember Swift Boat Veterans for Truth? How about Special Operations For America? The only things that make a bigger mess of American elections than our wars are the people who fight them.

2. The parties are just using us as poster children. Civilian political candidates use formations of uniformed service-members as a backdrop so often it should be its own Internet meme. It was only natural for the parties to shift the service-members to the fore once they took off the uniforms.

1. We actually do feel entitled! It’s the ultimate fig leaf. If military veterans really are principled guardians of American values returned from fighting in distant lands, they’d love nothing more than to debate the merits of military service, the value of their experience, and how it can benefit them in service to the American people.

If he really wanted to demonstrate the character he says the military gave him, Anthony Brown would have responded to Gansler’s “real job” comment by turning the debate on all the other jobs and experiences he’s had since his time on active duty. It would seem that defending his record as lieutenant governor is more relevant than his military service record.

Instead, he used me and all the other vets in America as his personal deflector shield to turn Gansler’s attack back on him. By expressing indignation on my behalf, he essentially took my name in vain. Yet Brown fails to win the prize for arrogance this week thanks to the new campaign ad from Tom Cotton. The 30-second spot oozes the very sense of entitlement it hammers Pryor for accusing him of having. The levels of irony are boggling. Cotton even explicitly says that his former drill sergeant is an expert on having a sense of entitlement.

Maybe there’s a debate to be had over whether the ad’s intent meets the definition of the word “entitled,” but it certainly comes off as self-righteous. Its express purpose isn’t to dispute or debate; it’s to silence. Brown and Cotton may have taken different tones, but their message is the same: “I’m a vet, so you shut up.” It’s almost like a real-life version of “Fight Club”: The first rule of running against a veteran is that you do not talk about the fact that you’re running against a veteran. That’s a gross breach of the political process and, quite frankly, a spineless cop-out. Cotton doesn’t come across as feeling entitled to office, but he clearly demonstrates a sense of entitlement in dictating the course of debate. That may be worse than feeling entitled to office.

Gansler, Pryor and Metzenbaum (not to mention Duckworth’s former opponent Joe Walsh) are all guilty for clumsily approaching their rivals’ military service records. However, it’s notable that they displayed the same awkwardness as CNN reporter Jake Tapper did when asking former Navy SEAL Marcus Luttrell about the relative merit of his comrades’ death in Afghanistan.

It is equally remarkable that the veteran candidates all responded as angrily as Luttrell did to Tapper. Therein lies a genuine threat to democracy. If Luttrell can generate such backlash against the press for asking an honest question that it ceases public dialog on such an important subject, what impact can government officials have on the decision-making process if they can use their prior military service to bully their peers into silence?

If veterans want to prove they don’t feel entitled to public office, then they have to reject the belief that they’re entitled to have their service record sheltered from public debate.

DCG