Francis Ford Coppola's modern rejuvenation is one of the most unexpected and wonderful occurrences of contemporary American cinema. Almost entirely written off as a has-been who burned out while trapped in his mock-up Vietnam, Coppola's seeming early retirement after 1997's The Rainmaker appeared less premature but, if anything, belated. But Youth Without Youth was not merely Coppola's first film in a decade but his greatest in a generation, at least since 1983's Rumble Fish. The usual round of scathing late-period reviews greeted the director's work, but if one looks past a script that clearly reads better than it sounds aloud, Youth Without Youth becomes one of the most powerful expressions of the possibilities of the new cinema and, for all its reduced scale and budget, an astonishing leap forward in the classically minded Coppola's search for the Gesamtkunstwerk.

Francis Ford Coppola's modern rejuvenation is one of the most unexpected and wonderful occurrences of contemporary American cinema. Almost entirely written off as a has-been who burned out while trapped in his mock-up Vietnam, Coppola's seeming early retirement after 1997's The Rainmaker appeared less premature but, if anything, belated. But Youth Without Youth was not merely Coppola's first film in a decade but his greatest in a generation, at least since 1983's Rumble Fish. The usual round of scathing late-period reviews greeted the director's work, but if one looks past a script that clearly reads better than it sounds aloud, Youth Without Youth becomes one of the most powerful expressions of the possibilities of the new cinema and, for all its reduced scale and budget, an astonishing leap forward in the classically minded Coppola's search for the Gesamtkunstwerk.Based on the novella by Romanian author Mircea Eliade, Youth Without Youth wears its literary influences on its sleeves, introducing a 70-year-old Romanian intellectual, Dominic Matei (Tim Roth) at the end of a career spent unsuccessfully tracing linguistics to the origins of language. Despondent for a life wasted in solitary confinement, he returns home with plans to commit suicide, until a bolt of lightning strikes him as he crosses the street. Left horrifically charred, blind and near death, poor Dominic appears to suffer one final injustice before he shuffles off this mortal coil. Then, he makes a full recovery with breathtaking speed, not merely recuperating but aging backwards three decades.

This medical miracle naturally baffles the doctors and nurses tending to Dominic, who will eventually display even more supernatural feats as it becomes evident that his entire genetic makeup has changed. With the Nazis at Romania's doorstep, officers soon come calling for Dominic to study the man who has caught the attention of Der Führer himself. Ergo, Coppola frames the film's first half as an international thriller, complete with spies, Nazis and a constant sense of fear. But the director splits the antagonizing forces into dualities of external foes—the aforementioned Germans—and internal strife brought on by the development of a second personality, the embodiment of Dominic's mysterious condition, that skews his perceptions of reality. Already putting the audience on edge, Coppola takes things one step further with a visual style that blurs the realm between reality and dream. The frame routinely tilts 90, even 180 degrees, hallucinatory, often erotic imagery moving imperceptibly from fever dream to reality as Dominic's primary medical observer and friend, Prof. Stanciulescu (Bruno Ganz) notes that the man actually is enjoying the company of the fantasized-about Woman in Room Six, who may also be a German spy.

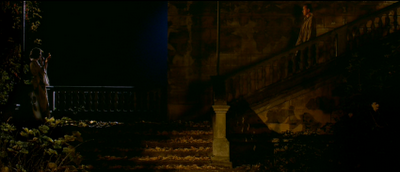

These are confusing threads made more difficult by the aesthetic style, which starts superimposing images, using brief close-ups to recontextualize repeated shots and provide vague clues, and digitally inserting Dominic's doppelganger when not using a Gollum-style series of shots to make Roth seem like two different people. If one takes a step back, however, Coppola's genius becomes clear. Using the free possibilities of digital cinema and easy post-production, Coppola actually returns to the early days of cinema with silent techniques. The superimposed imagery harks back to silent editing, while the use of suggestive color schemes—honeyed yellow in daylight, ice-blue at night—likewise recalls early color tinting, particularly the blue of Expressionist horror's chilly nighttime shadowplay. This is an art history expression of the duality expressed between Dominic's meek, lovelorn corporeal being and the Nietzschean Übermensch of his split personality, a rational but forceful being that looks forward to the new age of mankind with Dominic as the first of a new species. Applied to the aesthetics, Coppola likewise ages backwards along cinema's timeline only to develop new possibilities and ways forward.

Before long, one can hardly separate the themes and structure of the film's narrative from Coppola's own creative life. While still recovering from his extensive burns, Roth is wrapped from head to toe in bandages, making a mummy of a still living man who already feels dead for having failed his life goal. Perhaps Coppola identifies with the man prematurely mummified, enshrined while still alive as if reminding detractors that he's not dead either, regardless of how much people insist on speaking of the director as if he died in 1980. But the lightning strike that nearly killed Dominic winds up rejuvenating him and giving him a second lease on life and his artistic dream; it is all but impossible not to see the correlation to digital filmmaking, which must have threatened the old guard like Coppola with obsolescence but now gives him a whole new lease on artistic creativity. Just think, one of the most legendary directors alive, four decades into his career, is now an independent filmmaker thanks to the potential of digital.

Coppola does not waste the opportunity. Mihai Malaimare's gorgeous cinematography surely stands as one of the finest use of digital cameras in film to date. Eschewing the digital noise of Michael Mann's late-career format explorations, Coppola and his cinematographer instead made impossibly crisp imagery that can undulate and shift on a dime. Coppola moves the camera less, relying instead of Walter Murch's rhythmic editing to progress immaculately composed static shots to not only create dynamic motion but also to handle the transitions in and out of dreams. Murch gives that blurry divide its ambiguity and, combined with the film's gentle leaps through time, finds the balance between the concrete and the abstract, between reality and dream. And after all, isn't that divide what the cinema is all about?

Other artforms feature as well. Osvaldo Golijov's score mixes whispers of Coppola's love of opera with modern compositional touches, crafting textures of moody, mysterious fragments and lilting motifs that effortlessly traverse the rich cultural history and varied narrative styles the film employs. As for literature, it drives the film. Refreshed and escaped from Nazi Romania, the newly young Dominic resumes his work on tracing the Ur-language, research aided by his ability to glean the contents of books simply by waving a hand over them. Dominic's sudden ability to speak fluently in practically any language opens the possibilities for paths back through time, and it's no coincidence that, when he finds himself in neutral Switzerland in 1939, he keeps on his nightstand one of the earliest pressings of Joyce's Finnegan's Wake, another work of dreamspace-set lingual deconstruction.

To travel down this alternate plot, as well as to further the film's use of duality, the tone of the film abruptly switches around the halfway point from a dark, moody psychological and quasi-political thriller to a romance for the ages, literally. While hiking one day, Dominic meets Veronica (Alexandra Maria Lara), the spitting image of the first love he, in young Scrooge fashion, lost for his single-minded pursuit of career. But Veronica is not merely the reincarnation of Dominic's beloved Laura but of Rupini, one of the first disciples of Buddha; a storm traps her in a cave, and when Dominic leads a party to find her, he discovers the young woman speaking perfect Sanskrit, this reverted form only expelled after tracing the real Rupini's remains.

Coppola sets the romance that blossoms between the two as one of Dawn and Dusk, inextricably linked but doomed to separation for the balance of the cosmos. Veronica is a perpetual youth, her buoyantly smiling visage containing within it the memories of ancient civilizations, a subconscious knowledge of the birth of man. Meanwhile, the invigorated Dominic prepares for a foreseen apocalypse and and end of humanity as we know it as they evolve into a new lifeform. His rejuvenation is merely a reflection of entering his moment, just as Veronica's sudden aging around Dominic shows the last vestiges of light slowly dying at nightfall. This cosmic reading turns the the little-r romance between the two into capital-R forbidden love and destined separation. When Dominic whispers "I've always loved you" to a sleeping Veronica, he sounds like a corporeal incarnation of eternal forces using vocal cords to express something otherwise communicated on an epic, silent level.

Quite a lot of Youth Without Youth is obscure, not in any referential sense but in the unorthodox structure of stilted language. Mirror imagery abounds, much of it digitally manipulated to divide the movements of Roth and his "reflection"; there are even strangely matching shots separated by huge gulfs of time, such as the shot of a zapped Dominic lying on the ground with red, peeling flesh surrounded by fire at last matched with the man lying snow-covered. In the film's elision over time and space, details that might clarify the shifting aims and point of the film get lost in a haze, and the mysterious ending dissipates into metaphysical, emotional and philosophical abstraction. The film's tour through various cultural histories all works to the benefit of cinema, and Coppola even addresses his own work with seeming immodesty. But then, only a fool would deny Coppola's place in cinema's rich timeline, and the whispered, Willard-like narration and less-ironic golden tones of The Godfather's tinting mingle beautifully with the reverence for silent cinema and the more static, compositionally pure style of Ozu that Coppola has said he wants to imitate now.

The characters and visuals of Youth Without Youth are perpetually divided by the material's obsession with dualism of young and old, hallucination and reality, and conjured roses are used to demonstrate the search for a middle ground. As Dominic asks his doppelganger to put two roses on him, he falters when thinking of a place to place a third one, a simple question that becomes emblematic of the spiritually nomadic journey Dominic takes throughout the film. The third rose's placement will dictate the balance, and when it finally appears at the end, its simple, prose-poetry beauty feels a powerful statement of renewed intent by the filmmaker. But then, flowers have long been signs of revolution.