Prufrock and Other Observations by T.S. Eliot

It’s often thought that modernism is difficult, inaccessible, not the sort of thing most readers will enjoy. When the BBC carried out a survey to discover Britain’s favorite poet though the winner was T.S. Eliot, high priest of Modernism with a capital M.

It’s not a surprise of course that the winner was a poet taught in schools, few people read poetry after school (poetry often seems more written than read). I find it a cheering result, at least partly because Eliot isn’t the easiest poet to read (though he’s not nearly as hard as his reputation might suggest). It’s certainly a much better result than the BBC’s 2003 best novel survey which came up with a top 100 list that was staggering for its obviousness and mediocrity.

I didn’t vote in the poll, but if I had I’d have voted Eliot too. The reason I’d have voted Eliot isn’t The Wasteland, masterpiece as that is, but because he wrote what is probably my favorite poem – The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.

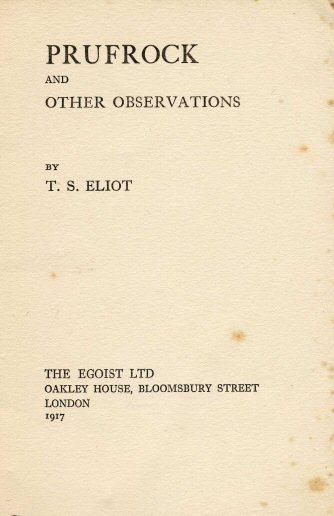

Prufrock and Other Observations was first published by The Egoist in 1917. Nowadays there’s a lovely little Faber and Faber imprint – pocket sized and printed on good quality paper and generally a pleasure to hold (as the Faber poetry volumes tend to be).

Prufrock and Other Observations contains twelve poems of varying lengths and styles. Of these the big beast is clearly The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, but there are other stand-outs such as Portrait of a Lady; Preludes (“And then the lighting of the lamps”); Rhapsody on a Windy Night; Morning at the Window; Aunt Helen; Hysteria; La Figla che Piange; as well as arguably lesser efforts such as The Boston Evening Transcript; Cousin Nancy; and Mr. Apollinax. I suspect Conversation Gallante is also a lesser effort, but one I liked and I’ll talk a bit more about below.

There isn’t a single poem in this collection that hasn’t been the subject of exhaustive academic analysis, none of which I have read. There isn’t a poem here which hasn’t been comprehensively picked clean of references, inspirations, influences and subtexts. I don’t do this for a living though, nor do I have exams to sit, which means that I have the luxury of just reading the poems for themselves, taking from them those parts that speak to me.

Here, after an introductory quote from Dante in the Italian, are the opening lines of Prufrock:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table;

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells:

Streets that follow like a tedious argument

Of insidious intent

To lead you to an overwhelming question. . . 10

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Let us go and make our visit.

This is profoundly alienated language – “muttering retreats”, “restless nights in one-night cheap hotels”, “Streets that follow like a tedious argument”. There’s a sense of a grubby, tawdry reality. This is an internal monolog weighed down by the futility of its own debate (I’m aware there are other argued interpretations).

What follows is a man arguing with himself as to whether or not to confess his love for a woman. He plays through the whole encounter in his mind – the journey to her, climbing up her stairs, and then the impassable barrier of indifferent decorum.

Time for you and time for me,

And time yet for a hundred indecisions

And for a hundred visions and revisions

Before the taking of a toast and tea.

The poem is rich with images taken from religion and myth – opening with Dante, referencing Hamlet, John the Baptist, Lazarus, mermaids. Against all that though is the suffocating mundanity of a room with tea and polite conversation and the sheer impossibility of breaking through to something that actually has meaning, something profound (Mr. Apollinax brings out these contrasts much more clearly, but for me to lesser effect).

The poem is suffused with desire:

Arms that are braceleted and white and bare

(But in the lamplight, downed with light brown hair!)

but there is no certainty that the desire is in any way returned. Polite Edwardian England has no place in it for passion. Prufrock, middle-aged and painfully conscious of his own absurdity, has no power to shake the age and transform it.

Eliot then shows the gap between the dream and the suffocating reality, leading to some of the most painful lines I have ever read:

Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?

I shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach.

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.I do not think that they will sing to me.

That gap, that pause for reflection between stanzas, makes the line “I do not think that they will sing to me” hit like a hammerblow. It underlines the full tragedy of Prufrock’s (far from unique) situation. It is a poem which speaks of disenchantment, not just in the obvious sense but in that referred to by Josipovici in his What Ever Happened to Modernism? Prufrock is modern, as is the world, and our old dreams are dead and all we have in their place is form emptied of substance.

Preludes and Rhapsody on a Windy Night also explore the disillusionment brought by mucky prosaicism and the sheer pain of existence among indifference, as does Morning at the Window (repeated below in full):

They are rattling breakfast plates in basement kitchens,

And along the trampled edges of the street

I am aware of the damp souls of housemaids

Sprouting despondently at area gates.The brown waves of fog toss up to me

Twisted faces from the bottom of the street,

And tear from a passer-by with muddy skirts

An aimless smile that hovers in the air

And vanishes along the level of the roofs

Again there’s that impressionistic conjuring of the city and the urban environment, there’s that feeling of terrible isolation and there’s that wonderful and surprising juxtaposition of images – “the damp souls of housemaids”. Above all though, for me, there is disenchantment and alienation. If this were religious poetry I would talk here as I would have with Prufrock of how the sacred remains barely visible but forever out of grasp in a fallen world, but it’s not religious poetry and the world isn’t fallen because the truth is worse than that. If the world were fallen we could climb back up, be restored to grace, but grace was only ever a dream and human voices have woken us.

The last poem I’ll single out to discuss is much lighter in tone, and it’s Conversation Gallante. Here it is, also in full:

I observe: ‘Our sentimental friend the moon!

Or possibly (fantastic, I confess)

It may be Prester John’s balloon

Or an old battered lantern hung aloft

To light poor travellers to their distress.’

She then: ‘How you digress!’And I then: ‘Someone frames upon the keys

That exquisite nocturne, with which we explain

The night and moonshine; music which we seize

To body forth our own vacuity.’She then: ‘Does this refer to me?’

‘Oh no, it is I who am inane.’‘You, madam, are the eternal humorist

The eternal enemy of the absolute,

Giving our vagrant moods the slightest twist!

With your air indifferent and imperious

At a stroke our mad poetics to confute — ‘

And- Are we then so serious?’

This is Eliot in much more playful form. It’s not a great poem as say Prufrock is, but it does capture nicely a certain kind of flirtatious conversation, of the woman constantly slightly ahead of the narrator. The majority of the speech is the man’s, apparently driving the conversation, but at each turn the woman outwits him and he finds his flurry of words effortlessly parried with a single line.

There is of course again here an example of the fantastic being defeated by the mundane, but for me at least without the despondency carried by the other poems. I’ve been in that situation, trying hard to impress someone who knows that’s what I’m doing and who doesn’t plan to make it easy for me, and there is an inherent comedy to it which Eliot is well aware of.

The poem illustrates one final point, which is that throughout this collection (and perhaps in Eliot’s poetry more broadly) it’s men who are sensitive and experience deep emotions for which they have no outlet. Women by contrast are sometimes attractive, but rarely reflective. Eliot is brilliant and his poetry is I think as good as art gets, but he writes firmly from a male viewpoint. Even with that though Eliot’s perception is so acute, his observations so universal, that I would have thought as many women as men would recognize themselves in his work.

In a way Eliot’s gender representations reminded me of a conversation I had years ago, where I described to a woman how as a teenager I’d sometimes been awed by girls I thought too cool to approach – utterly diminished by their impenetrably aloof beauty and unable to even speak to them. I’d naively thought it a uniquely male experience, but of course it isn’t. Her comment was that she’d had the same thing with some boys, and why wouldn’t she? Disillusion, desire, the need for something beyond the everyday, if these aren’t fundamental human experiences then what is?

Filed under: Eliot, T.S., Modernist Fiction, Poetry Tagged: Faber and Faber, Modernism, Prufrock, Prufrock and Other Observations, T.S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock