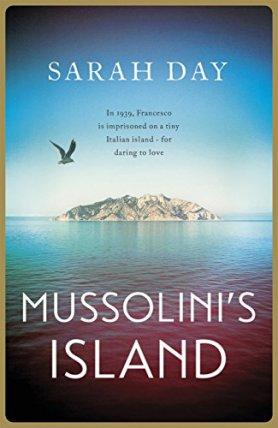

Last week’s spring Sofa Spotlight met with a great deal of interest and enthusiasm, so a big thank you for your support and appreciation. It is a pleasure to welcome the first of my Spotlight guest authors today – the talented and lovely Sarah Day, who I can’t help noticing has a large and committed fan base already! I first met Sarah at a mutual friend’s launch two years ago and knew the moment I asked about her own novel that it was something I really wanted to read. My patience and high expectations were rewarded; this is a genuine standout amongst the many excellent literary debuts I’ve read in over five years of running the Literary Sofa, and in the review following Sarah’s post about the setting of Mussolini’s Island you can find out why.

Last week’s spring Sofa Spotlight met with a great deal of interest and enthusiasm, so a big thank you for your support and appreciation. It is a pleasure to welcome the first of my Spotlight guest authors today – the talented and lovely Sarah Day, who I can’t help noticing has a large and committed fan base already! I first met Sarah at a mutual friend’s launch two years ago and knew the moment I asked about her own novel that it was something I really wanted to read. My patience and high expectations were rewarded; this is a genuine standout amongst the many excellent literary debuts I’ve read in over five years of running the Literary Sofa, and in the review following Sarah’s post about the setting of Mussolini’s Island you can find out why.

I approached the Tremiti Islands by boat. You can get a helicopter – faster, easier, more frequent – but I wanted to see them coming, tiny dots above the water, growing larger and larger until sheer cliffs surround you like prison walls.

I tried to imagine how my characters might have felt. My novel is based on the true story of a group of gay men from Catania, arrested and deported to San Domino during the Fascist era. It’s tempting to think it might have been fun, to be removed from a society that condemns you, to finally be free to express your sexuality openly, but looking up at the cluster of tiny islands, it was so clear the opposite was true. This wasn’t an island paradise, a salvation from a city of persecution and terror. It was isolation, complete and unrelenting. They must have been terrified.

The first thing that struck me was the silence. A crowd of us piled off the boat, but everyone had prearranged transport, and I was quickly alone. I wheeled my suitcase up a steep hill, stubbornly refusing the many offers of lifts from passing visitors and islanders. I had come to get a better sense of the place, how my characters might have experienced it in the year they spent imprisoned on the island. Getting into a car or a bus felt oddly wrong.

But sense of place isn’t just about the detail. It runs through the veins of a book. Visiting the locations changed everything – not just the streets, the buildings, the foliage, but entire swathes of plot, and characters with it. I suddenly understood so much more about how they might have acted, what they might have experienced – details I could never have gained from books, however many I read.

What I wanted from this trip, most of all, was to find the prison – a long, low dormitory in which the men were locked during the night. After two days of exploring San Domino, I finally plucked up the courage to ask the locals for help. I hadn’t wanted to, at first. I didn’t know where to start. But my Dad texted, and reminded me of a recent article about the San Domino prisoners which quoted a man who still remembered them, so many decades later. I held up my phone to a waitress, and asked for Attilio. Ten minutes later, we were knocking on his door.

Attilio has lived on San Domino for his whole life. He speaks no English, and my Italian doesn’t stretch much beyond a stuttering, ‘Hello. So sorry to bother you,’ quickly googled on my phone. But he understood what I was asking about. We spent a morning laughing and smiling and walking the island, searching for someone who could translate for us. We visited everyone – the tourist office, a few shops, we even had orange squash with the Priest – but no one spoke English.

Eventually, Attilio’s friends Luigi and Elena came round, lending their services as translators. We had lunch, and chatted about the prisoners, Attilio’s memories, the island’s fascist past. My book began to open up in front of me – so many possibilities I had never thought of before.

Before I left, Luigi took me for a walk with his dog along the shore. He pointed out locations he thought the prisoners might have visited, coves they would have bathed in, land they would have worked. He picked flowers, pressed them into my hands. He told me how important the story was, how I should make sure to tell it right. He told me that, though what had happened was wrong, so wrong, the prisoners had lived for a short time in paradise.

Thank you to Sarah for this beautiful piece giving such a sense of the history and the people of San Domino, as well as the physical location.

This brave, complex novel uncovers a dark and shocking historical episode which will be unknown to most English-speaking readers, as it was to me. It makes certain demands, with a large, almost entirely male cast and multiple threads and timeframes, but the plotting is smoothly executed and the reward is a deeply moving and immersive story. As both reader and writer, I found so much to admire: the prose has an elegant clarity and the sense of location is very strong. There is no shying away from the sex, the bigotry or from the ugliest and most traumatic incidents and this honesty is crucial to the integrity and emotional impact. Another important consideration is that Mussolini’s Island is a book intimately concerned with the fate of a gay male community, written by a woman. Much has been said on the wider issue, but I feel that Sarah Day’s insight and sensitivity make her debut a shining example of what authors can achieve by daring to breach the boundaries of personal experience. I hesitated over my own right to an opinion on this, before realising it is intrinsically related to this same question. Fiction can transport us beyond ourselves, extend our understanding. The challenge is to do it as well as it’s done here.

Speaking of which, if you missed it, do read Saleem Haddad’s recent guest post on Shelving the ‘Gay Novel‘

*POSTSCRIPT*

Next week I will be welcoming Laura McVeigh, author of Sofa Spotlight title Under the Almond Tree, with a Writers on Location post on Afghanistan.

Advertisements