The last couple of months seem to have raced by. As usual I’m juggling several projects including a new mentoring role on the Retreat West novel course, which I am really enjoying, and gearing up to start writing my own. Today’s guest post by Pete Papathanasiou may be the first in a long time but it’s going to be worth the wait. Having previously featured his Greek-Australian adoption memoir Son of Mine and a fantastic post Pete wrote about resilience on the road to publication, I’m delighted to welcome him back to the Sofa with a Writers on Location on the Australian Outback. It’s the setting of his debut crime novel The Stoning and my review follows at the end:

The last couple of months seem to have raced by. As usual I’m juggling several projects including a new mentoring role on the Retreat West novel course, which I am really enjoying, and gearing up to start writing my own. Today’s guest post by Pete Papathanasiou may be the first in a long time but it’s going to be worth the wait. Having previously featured his Greek-Australian adoption memoir Son of Mine and a fantastic post Pete wrote about resilience on the road to publication, I’m delighted to welcome him back to the Sofa with a Writers on Location on the Australian Outback. It’s the setting of his debut crime novel The Stoning and my review follows at the end:

The Australian outback is not for the faint-hearted. To begin with, it is dangerously hot, with daily temperatures that soar above 50 degrees Celsius. It is vast, with thousands of miles between petrol stations and drinking water and medical supplies. If you need help, don’t expect it to come quickly. And the outback is filled with animals, and possibly even a few humans, who want to see your demise. Honestly, where better to possibly set a crime novel…?!

To most of the world, Australia remains a wild, untamed place. Its distance from other countries and island geography add to its exoticism and mystery, along with its vast open spaces, unending skies and horizons, and the world’s oldest civilization. It all becomes rich inspiration for writers and compelling stories for readers, and especially if you’re writing in the genre of crime.

I have traveled extensively through the outback, which comprises two-thirds of the Australian continent. It is very easy to lose track of both your bearings and time. The primal landscape feels endless, which can readily disorientate and compress the concept of time. You get covered in dry sweat and red dust, which altogether stick to your body and form a suffocating second skin. The light is so sharp and bright that sunglasses aren’t just an accessory – they’re an essential survival item. It’s the same for water – more than you ever thought you could drink, and that only seems to swiftly reappear through the pores of your sunburnt skin. The dirt is so dry, red and dark, it’s as if the earth has been blowtorched.

And then there’s the outback’s many human characters. The barflies, the publicans, the farmers, the miners, the motorbike gangs, the outlaws, the highway wanderers and hermit loners and killers on the run. Combined with the maddening heat, it creates a powder keg situation for the struggling cops endowed with the largest beat in the world.

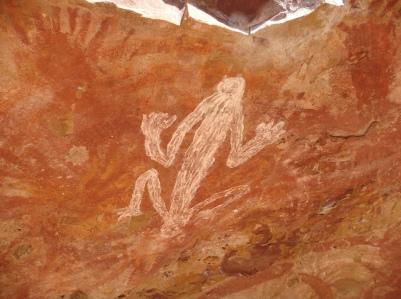

But while perilous, the outback is also staggeringly beautiful. It is cinematic to gaze upon and utterly calming in its stillness. When you find a rare watering hole for a swim, you feel decades younger. The beer is the coldest you’ll ever taste. The world’s oldest civilisation, the Indigenous Australians, have inhabited the outback for 50,000 years and continue to hold a deep spiritual connection. And if you’re super quiet and concentrate your focus, you can even feel like you’re breathing in synchrony with the land itself.

But just remember to keep breathing… because there is so much in the outback that is actively trying to stop you.

Thanks to Pete for this great post, unusual in my long running Writers on Location series as a place the author isn’t particularly selling!

As the northern hemisphere heads into winter, this atmospheric crime novel transports the reader to the intolerable heat and endless expanses of the Australian outback. Vivid as this is, it is far more than a geographical setting which the author knows intimately – the social and political context in which the desolate and divided small town of Cobb finds itself is just as important. It is clear from the very outset – along the all too familiar lines of a woman’s life cut short in horrific circumstances – that the author does not shy away from ugliness and brutality. There’s a lot of it and very little hope in this town where economic decline and an additional layer of racism following the establishment of a refugee detention center prove a toxic environment for city cop George Manolis, called in to investigate the death by stoning of schoolteacher Molly.

Manolis is a nuanced and empathetic protagonist and, as a de facto outsider, an effective foil for the apathy, prejudice and obstructiveness of the local police and community. His frustration and despair at butting up against such attitudes – openly voiced in dialog that will make you flinch – are a driving force in this cleverly woven investigation, the first in a series. As the praise this debut is garnering from critics and crime fiction fans demonstrates, it stands out in that highly competitive genre, in part for a willingness to shine an unforgiving light on real world injustice and inequality that was its main strength for me.

*POSTSCRIPT*

My first November post will be a round-up of four novels I’ve enjoyed. This is a format that I brought in this time last year that proved popular and means I can give a mention to more books than I can cover in detail.