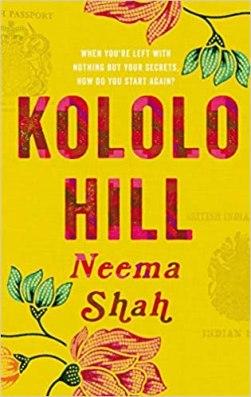

This week I’m delighted to be hosting the first Writers on Location post of the year, courtesy of talented debut author Neema Shah. Her novel Kololo Hill is set in Uganda and the UK during the expulsion of Ugandan Asians by dictator Idi Amin in the early 1970s. Surprisingly, I have vague memories of this despite being very young at the time, but until now I had never read a novel documenting the brutal exodus which upended so many lives. Neema joins me today to share a research trip to Uganda which really paid off, based on the results: the geographical and cultural settings of Kololo Hill are exceptional, and that’s not all. My review follows:

This week I’m delighted to be hosting the first Writers on Location post of the year, courtesy of talented debut author Neema Shah. Her novel Kololo Hill is set in Uganda and the UK during the expulsion of Ugandan Asians by dictator Idi Amin in the early 1970s. Surprisingly, I have vague memories of this despite being very young at the time, but until now I had never read a novel documenting the brutal exodus which upended so many lives. Neema joins me today to share a research trip to Uganda which really paid off, based on the results: the geographical and cultural settings of Kololo Hill are exceptional, and that’s not all. My review follows:

What if you were forced to leave everything you know and love behind, to start again? What if you were expelled from the only country you knew, given 90 days to vacate your home and business? That’s exactly what happened to 80,000 Ugandan Asians in 1972. They were expelled by President Idi Amin, told to give up all that they knew, say goodbye to friends and in some cases, family. Many who arrived as refugees in the UK had British passports. Inspired by these events and my own family background – my grandparents left India for East Africa during the 1940s – I wanted to explore this history in my debut novel Kololo Hill.

So, in May 2017, I set off on a one-week trip to Kampala, where many of the Ugandan scenes of my story take place. I came out of the airport and felt that my novel was coming to life around me. Uganda is known as the Pearl of Africa and it’s no wonder; with its rich vegetation and trademark red earth, it’s home to mountain gorillas, crocodiles, elephants and hundreds of other animals, over 1,000 species of bird and 1,242 species of butterfly.

But as I was about to find out, I’d barely scratched the surface of the country with my research so far. I toured Kampala with a local guide, eating a traditional Ugandan meal, including various types of posho —ground and boiled maize boiled and mashed green plantains (known in Swahili as matoke). I chewed sugar cane so sweet that it made my jaw zing and drank coconut water straight from the green outer shell. I spoke to local Ugandans about their views of Idi Amin, who’d reigned over the country for eight long years, promising to restore wealth back to ethnic Ugandans after taking it away from the ‘money-grabbing’ Asians who’d settled in the country in the colonial era.

I visited a few dukan, the catch-all Hindi and Gujarati name for any shop run by Asians. Although most of the expelled 80,000 never came back to Uganda, a few returned and were later joined by new arrivals from the Indian sub-continent. Despite only spending a week in this wonderful country, I felt a sense of loss when leaving. I could vividly imagine how heart-wrenching it must have been for those Ugandan Asians forced out of their beloved, beautiful country forever.

Visiting Uganda was both fascinating and moving. Had I tried to finish my novel without visiting the country, I feel I would have done a disservice to those who survived and suffered during that time. I’d like to think that my novel is all the richer for that valuable research trip.

Many thanks to Neema for this wonderfully atmospheric piece that captures the extra layers of nuance and understanding that on-site research can bring to a novel.

IN BRIEF: My View of Kololo Hill

I first heard about this book long before publication and it was a joy (but no surprise) when it exceeded my high expectations. For all that the first chapter makes a perfect case study in how to open a novel, its shocking scenes made me apprehensive; I recently wrote about the value of books on difficult subjects but every reader has their limits and this nudged at mine. However, it soon became apparent that one of the strengths of this novel is the delicate interplay between terrible cruelty and injustice and a compassion and humanity which comes through in the story, reflecting the author’s intentions in telling it.

Kololo Hill excels in its examination of universal themes like cultural identity, racism and belonging through the more intimate lens of the characters’ personal dilemmas, grief and betrayals – I felt them, and their desperation, acutely. Beyond the despotic regime, there is an admirable even-handedness to the portrayal of the different groups, underlining that they are made up of complex and flawed individuals. Neema Shah’s keen eye and poetic turn of phrase are equally well deployed in portraying the lush beauty of Uganda and the family’s traditions, and later their hard landing in a cold, drab and often (but not always) unwelcoming UK. The descriptions of food are mouth-watering and I loved the occasional bursts of their mother tongue. For some, this was the second time they had uprooted between continents, further complicating the notion of where and what home is and how incomers are treated. There are various parallels between the second half set in the UK and Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, Sunjeev Sahota’s The Year of the Runaways and Small Island by Andrea Levy; this debut novel warrants comparison with these titles on literary quality and cultural/historic significance, showing us other lives while making us look hard at ourselves.