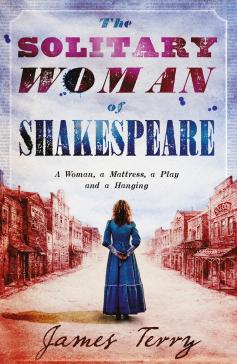

If you’re a keen reader of fiction it’s inevitable to find that certain themes crop up again and again and we all have our favourites. I can’t get enough of dysfunctional families, relationships on the rocks and New York novels (though I try not to read similar titles back to back); there are some themes and trends I am done with! Regardless, it’s always refreshing to stumble across something a bit different you really enjoy, which was the case for me with today’s featured novel The Solitary Woman of Shakespeare. The atmospheric setting of late 19th century New Mexico was only one of its attractions (the rest of which I discuss in the review that follows), but I’m very pleased that author James Terry joins me to share the discovery of a hidden treasure in his home state:

If you’re a keen reader of fiction it’s inevitable to find that certain themes crop up again and again and we all have our favourites. I can’t get enough of dysfunctional families, relationships on the rocks and New York novels (though I try not to read similar titles back to back); there are some themes and trends I am done with! Regardless, it’s always refreshing to stumble across something a bit different you really enjoy, which was the case for me with today’s featured novel The Solitary Woman of Shakespeare. The atmospheric setting of late 19th century New Mexico was only one of its attractions (the rest of which I discuss in the review that follows), but I’m very pleased that author James Terry joins me to share the discovery of a hidden treasure in his home state:

Down in the arid scrublands of southern New Mexico, sixty miles from where I grew up, lies a ghost town called Shakespeare. The Stratford Hotel, constructed of adobe bricks, still stands on dusty Avon Avenue alongside a handful of other buildings preserved in their original condition. One could be forgiven for thinking this place an apparition of Prospero’s conjuring. More wondrous yet, the town is still inhabited, and not only by ghosts.

When I first visited Shakespeare, in the early 1990s, I had the opportunity to meet one of its two remaining inhabitants, Janaloo Hill. She was in her mid-fifties then and still strikingly beautiful. Tall, rake-thin, with long black hair, she radiated quiet poise. Photographs from her New York modeling days were displayed beside historical memorabilia in her livingroom-cum-museum in Shakespeare’s old mercantile store. I was enchanted. Who was this remarkable woman? Why was she living in a ghost town? And how did this desert hamlet ever come to be called Shakespeare?

Then, in 1879, as if from the pages of a Shakespeare comedy, along came two men named Boyle, one a colonel, the other a general. Some accounts claim they were brothers, others that their shared surname was mere coincidence. They were purportedly of British origin, one of them also a Shakespearean scholar. The Boyles believed there was still silver in the hills, but they would have to cleanse the town of the taint of fraud that hung over its previous incarnation (bogus diamond mines) if they were to attract the capital needed to prove it. They had to give the town a new name. Something synonymous with Civilization. Quality. A name for the Ages.

Shakespeare lay derelict and abandoned until 1936, when Frank and Rita Hill bought the townsite and a large piece of land around it for the headquarters of their modest cattle ranch. Enchanted by the town’s history, they made it their mission to preserve it from the ravages of time. By the time of my visit to Shakespeare in the early ‘90s, Frank and Rita Hill had long since joined the cast of colourful characters buried on the hill overlooking the town, and the job of tending the town and its ghosts had passed on to their daughter, Janaloo, who grew up an only child in a ghost town and continued to live in the former old mercantile store, as her parents had before her, with no electricity or running water. One day a week she offered tours to the public, relating the history of Shakespeare, sometimes reenacting scenes from its history with the help of friends from the nearby town of Lordsburg.

But something of that brief encounter with Janaloo Hill must have settled deep in my psyche, for what finally emerged as the core of the novel was the concept of a solitary woman, all alone in a town of men.

Janaloo Hill died of cancer in 2005. Her husband Manny continues to live in Shakespeare, giving guided tours twice a month.

Thanks to James for this poignant and evocative piece. I’ve been fortunate to visit the Southwestern USA several times but have yet to make it to New Mexico. Now keener than ever to remedy that!

When ‘adventurous gal’ Abigail crosses the continent for a new life in the ‘Territory’ and marriage to a stranger, she gets both more and less than she bargained for, and no female company at all in the mining town of Shakespeare. With this premise, James Terry strikes narrative gold. Abigail is a spirited and engaging character at the center of a colourful cast and the author handles female perspective well. He also captures the geographical setting, the historical period and the strange dynamics of an isolated community where the protagonist is surrounded by men who are missing female companionship (to put it politely). This story holds some surprisingly sexy and romantic moments, along with a few that are about as crude as it gets, although in fairness it’s completely justified by the context. This is a touching novel written with heart, energy and a lot of humor – the perfect tonic as winter closes in.

*POSTSCRIPT*

There will be no post next week as I’m off to Paris. It’ll be a strange feeling going back for the first time since publication of my novel Paris Mon Amour – I enjoyed setting it there so much I might just do it again. For now, here’s my recent interview for Linda’s Book Bag – we had a great chat and the fantasy movie casting was particularly fun!