It’s really heartening to see the Spring Spotlight guest author series get a good reception, especially at a time when those with new books coming out need all the support we can give. Thanks to all of you for reading, to Eleni Kyriacou for her post on 1950s Soho and Hannah Persaud for last week’s fascinating piece on writing about an unconventional marriage.

It’s really heartening to see the Spring Spotlight guest author series get a good reception, especially at a time when those with new books coming out need all the support we can give. Thanks to all of you for reading, to Eleni Kyriacou for her post on 1950s Soho and Hannah Persaud for last week’s fascinating piece on writing about an unconventional marriage.

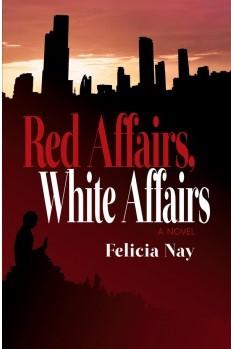

Today it’s time for the only Writers on Location post to emerge from my spring selection and I’m delighted to welcome German author Felicia Nay to share her experience of Hong Kong, setting of her debut Red Affairs, White Affairs. The novel won the Cinnamon Press Novel Prize in 2018 – doubly impressive for someone not writing in their native language. It will be released on 6 April and the print edition is available directly from Cinnamon Press.

No, it wasn’t love at first sight. ‘You don’t like our Hong Kong,’ the travel agent blurted out when, barely twelve hours after my arrival in the city, I begged her to get me a ticket on the next plane out. I didn’t dare contradict her. My dislike of the city was almost violent, something I had never encountered elsewhere. If somebody had predicted that one day I would write a novel born out of nostalgia for it, I would have doubted the person’s sanity.

That was in the early 1990s, and I had just spent five months in Mainland China, hand-washing my clothes and mixing with students who only had hot water twice a week but showered me with food and friendliness. It also was extremely safe. Hong Kong, in comparison, seemed megalomaniac, impersonal, hectic. Traces of that early shock can be found in my narrator, Reini, who comes to Hong Kong with her experience as an aid worker in the Sudan. Professionally programmed against inequality and poverty, she feels deeply uncomfortable with what she labels Hong Kong’s ‘cut-throat capitalism’.

I started to learn Cantonese, waded through the puddles in wet markets, had tea in diners populated by elderly locals. I also had Cantonese friends, people who were comfortable mixing with expats. Under a veneer of foreign education and global middle-class habits, they were surprisingly Chinese, preferring Traditional Chinese Medicine to Western medicine, consulting almanacs, eating congee as comfort food. And the more I learned, the more I fell in love. Lesson Number Three: knowledge and understanding breed love and ownership.

I started to write the novel after my return to Germany, an act tinged with desire. Reini, my expat narrator, was born, and I gave her a head start. From the beginning of the novel, Reini is knowledgeable about Hong Kong, and speaks enviously fluent Cantonese. Still, she struggles with the culture around her; Chinese family life and the position of women, folk religion, Buddhism, the ‘superstitions’ and convictions that shape everyday life.

Researching the novel deepened my relationship with the city once more. Often, there were small discoveries, such as the origin of the cockatoos in Central Hong Kong, descendants of a pair set free during the Japanese occupation. These moments of awareness created part of the writing magic, presenting me with themes and images that blended seamlessly into the narrative, but which I could never have consciously come up with.

Oh, and if you’re wondering about Lesson Number One: always travel prepared. And believe in love at second sight, of course.

Thank you to Felicia for this lovely and very personal Hong Kong story. Like the novel, it has a transporting effect which has increased in value lately.

This is a debut of many dimensions; predominantly character-driven, it’s the story of Reini/Kim, an independent, open-minded single woman in her thirties. Whilst she can be intense company, occasionally at the expense of narrative drive, I found Reini realistically complex, flawed but well-intentioned, and engaging. It’s possible to imagine long interesting conversations with her in real life, and surely one of the signs of a great fictional creation is that they don’t feel like one at all. With her experience of radically different places and ways of life, Reini has an unusual take on just about everything, from a vantage point as someone who is more integrated than a complete outsider to Hong Kong but knows she will never entirely belong.

That leads neatly to the second strength of this book: its vibrant and immersive sense not only of geographical place, but of tradition, customs and beliefs; I’ve never been to China but it reminded me of travels in SE Asia when lucky enough to get a tour guide who really brings their knowledge and understanding to life. The book takes its intriguing title from a Cantonese phrase: ‘red affairs’ are lucky celebrations such as weddings and birth announcements, ‘white affairs’ are funerals and other matters related to death. It’s an apt choice for a novel which spans the breadth of human experience, with both mortality and the search for love as central themes. It captivated me and I’d recommend it as a great place to lose yourself and the way you’re used to looking at life.

*POSTSCRIPT*

There’s a break next week before the second half of the Spring Spotlight guest season, which promises more brilliant posts from Nicola White on Writing the 1980s in her crime debut A Famished Heart, Stephanie Scott on her debut What’s Left of me is Yours and finally Anna Vaught on the historical research for her novel Saving Lucia.