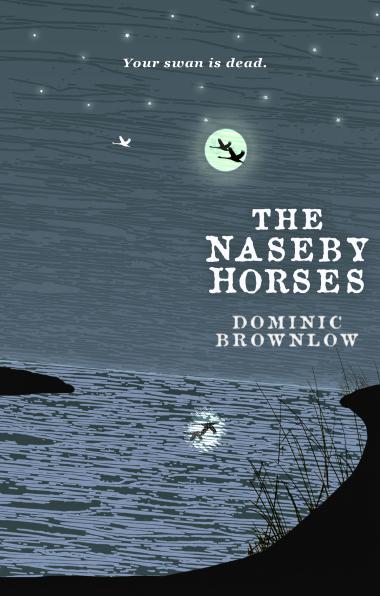

This week I am very excited to be hosting Dominic Brownlow and his outstanding literary debut The Naseby Horses, set in his native Fenland in eastern England. Whist his novel centres on the extremely well-travelled premise of a missing person (the teenage protagonist’s twin sister), the result is truly something else. It has various thematic overlaps with highly acclaimed bestsellers The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry and Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor. It’s in the same league in every respect, and deserves that degree of recognition.

This week I am very excited to be hosting Dominic Brownlow and his outstanding literary debut The Naseby Horses, set in his native Fenland in eastern England. Whist his novel centres on the extremely well-travelled premise of a missing person (the teenage protagonist’s twin sister), the result is truly something else. It has various thematic overlaps with highly acclaimed bestsellers The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry and Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor. It’s in the same league in every respect, and deserves that degree of recognition.

It’s alarming to consider how nearly this novel missed out on publication. I’ve often spoken of my admiration for small presses like Louise Walters Books which take a chance when other players in the business pass, and how vital it is to literary culture that these sometimes wildcard, sometimes (as in this case) inexplicably declined novels get through to readers. All that matters is that Dom persevered to find the perfect champion, and that The Naseby Horses are about to be released. More thoughts on the book at the end, but first, over to Dom for our visit to the Fens:

I grew up in a small village at the edge of the Fens. My dad was a farmer in its peaty heartland, his father and grandfather likewise, and part of its ‘soul’ has remained with me always, beckoning me back home to its immense solitary vistas and colossal skies. Much the same thing has happened to Simon and his family in The Naseby Horses. They have swapped a hectic life in London for one of supposed calm out here in the Fens, in a small village close to where Simon’s mother was brought up. This landscape is unquestionably peaceful, offering them a superficial notion of respite and recovery. To those who know little about it, and may call it dull or monotonous, it’s a place of mystery and uncertainty, guardedness perhaps. This made it the ideal fictional setting for a close-knit community seemingly unaffected by time, some of whom still harbor beliefs and traditions long renounced by the rest of society.

Suffused within these vast stretches of uninhabited land is a natural sense of loneliness and serenity and why it lends itself so openly to poetry and prose. It is a place that evokes thought. It is mostly silent. Simon is a deeply introspective character and the Fens quite naturally kindle this notion of isolation, of being lost. And there are, of course, the birds, and why, to Simon, the move from London was perhaps most suited. Undisturbed by modernisation, thousands of these birds: waders, water-fowl, migratory swans, swifts and swallows, raptors aplenty, score the wide open skies as though they were playgrounds. Simon adores the peacefulness and the birds and the landscape but he doesn’t really belong, and nor does his family.

Thank you very much to Dom for this atmospheric piece which conveys so much of his knowledge and bond with the area, which come across so strongly in the novel.

I hardly ever re-read anything. I don’t have the time and rarely feel the need. But this book cast such a spell on me when I first encountered it months ago that I wanted to check if my impressions held true. If anything, I was even more entranced by the strange, otherworldly mystery second time around, and by the stunning and original imagery which distinguishes Brownlow’s prose. I learned the word ‘eidetic’ (relating to or denoting mental images having unusual vividness and detail, as if actually visible), which could be said of the novel as a whole. It’s more than visual though – as someone with a professional interest both in the sense of smell and in writing about it (notoriously difficult), I am in awe of Brownlow’s ability to capture the olfactory – this novel is a feat of literary synaesthesia. You get it – this book impressed me a lot. But in the interests of critical balance, for authors with a talent for description, knowing when to rein it in is a skill of its own; it’s partly personal taste, but my feeling is that a striking image needs space and air around it for maximum impact on the page, and that leaner style puts the story center stage. There were moments when it seemed somewhat peripheral but this mattered less than in a more conventional narrative.

Simon is an unusual 17-year-old boy, precocious in some ways, childlike in others, and his medical condition influences both his and the reader’s perceptions of truth and reality. Ambiguity is a constant presence in this intellectually stimulating and complex work more at home in the territory of myth, philosophy and religion than that of everyday life – it’s almost a shock when someone breaks a mug, reminding us that this could be any family in the grip of an unbearable crisis. I enjoyed coming up with my own interpretations, sensing them shift, knowing others might see things very differently. The best part is that none of us would be wrong.

*POSTSCRIPT*

I can’t reveal what my next post is about but I can say I’m really looking forward to it…