Christine de Pizan, one of the first chroniclers of women’s writing

Throughout history, women have written. But it has only been at the far end of the twentieth century, the tiniest sliver of a second on the great clock of time, that their writing has been seen to be in any way equivalent to that of men. Oh for sure, there was the occasional ‘miraculeuse’ as the social theorist Pierre Bourdieu termed women like George Sand and Simone de Beauvoir, women who made it through the ranks in a way that looked as if it might be possible for anyone to do so. When of course it wasn’t, and they were startling anomalies. And in the present day, the category of women’s writing, with its subdivisions of chick-lit and mommy-lit and light romance and historical romance, is often considered more frivolous and lightweight than the thriller or science fiction novel. All of which is to say that the literary world has never really been a place that welcomed women in, and it does so with reservations even now.

And yet stories have had a great deal more power over women’s lives than over men’s. As soon as we begin to look into the past, it’s obvious how constrained women have been by the story of the ‘good’ woman, who she is, how she behaves, what she may expect. The stories available to women as guidelines for living have traditionally been few and uncompromising: women were supposed to be quiet, well-behaved, charming, gentle, tender. They were destined to be faithful wives and devoted mothers. The romance was their only socially permitted adventure, and so they had to make the most of it (one of George Sand’s heroines delays her engagement for 8 years, about 250 pages of incident-filled narrative, before succumbing to marriage and motherhood in the final chapter, which Sand recognised would be the end of her freedom and interest to the reader). Those who deviated from these rules were severely punished by ostracism from the community, confinement in mental hospitals, excommunication from the church, public disgrace, scandal and death. All this because of stories handed down from generation to generation! So much constraint, so much restriction, because of this dreadful paucity of narrative possibility.

But still, women wrote. They wrote because writing was compatible with confinement in domesticity. What they wrote, however, was inevitably marked by the differences imposed upon them. They wrote out of a completely different relationship to power than men enjoyed. They wrote out of exclusion from the places in society where decisions were taken. They wrote out of a narrower view of the world and the things people could do in it. And where exceptions arose and amazing women found ways to travel and organize and become pioneers in a field, they deserve our awe and admiration while taking nothing away from the others who did not find those precious loopholes. They were not easy to come by. Today, in many countries across the world, the situation for women is still one of restriction, too often accompanied by suffering and fear. The obstacles may vary, but consistently, across time and space, women have found their conditions of life, the options open to them, to be different to those enjoyed by men. It’s an ongoing reality, and one brought home to us most vividly and powerfully by the stories women get to tell. We need every story, and each one asks us to listen, not to judge.

The consciousness raising campaign of the 60s and 70s

These past few weeks, reading for a whole month of blogging about women’s writing has been quite fascinating. I’ve been almost shocked by the differences between the feminist writing that came out of the 70s and 80s and the genre fiction of today. Whilst the feminists fought for the right to be free of domestic chores, to be less confined by marriage, to have the choice of meaningful work, to bring up children in less constricted environments, the genre fiction of today paints a world in which women have rushed back to the realm of the Stepford wife. A successful marriage, a pretty house, lots of nice material things, these are the hard-won goals. And motherhood remains the country that feminism forgot; it demands the absolute sacrifice of women’s personal needs, desires and activities. I’m not saying this is necessarily wrong or lacking in value – but what does the radical swing in social aspirations mean?

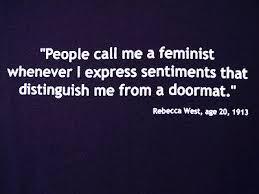

What has remained consistent throughout the recent period of literary history when women have been much more free to write whatever they chose, and to have lives lived according to their own principles, is the difficulty women have with accepting that other women may behave differently. In almost all the fiction and non-fiction I’ve been reading, the conflicts arise because women find it hard to live and let live. The choices and behaviours of others, if they run counter to their own, are too often understood to be offensive, wrong, in need of alteration. This difficulty is very obvious in the reception of women’s writing, too. How often are female characters damned for not being ‘sympathetic’? For not behaving, in other words, the way that the woman reader wants them to? Still there remains the tendency to prescribe female behavior – and it’s most noticeably done by other women. If the great historical battle of feminism was the right to be something other than a gentle nursemaid and competent housekeeper, why on earth should we spend so much time and energy squabbling over a new definition of how women should be? And worst of all, why should the mirage of ‘strength’ be the one that dominates these prescriptions? ‘Strength’ if we mean constant energetic, fearless engagement in life, is an unlivable idea. Real strength, achievable and sustainable strength, is about flexibility, gentle discipline, understanding, compassion, and the acceptance of weakness.

But surely this goes a long way to explaining how come women survived – were complicit with – those endless centuries of history in which only a few stories were available for women’s lives. If there were one great overriding narrative, one way to be, women could measure themselves against it and feel secure, even superior to other women who did not match up so well. But that is to understand the meanness of women to one another as pure aggression, and I don’t believe that’s so. I think it’s actually about the unplumbed depths of women’s insecurity. When women fail to give each other the benefit of the doubt, it’s because the other’s difference awakens their insecurity. And by some twist of psychology, personal insecurity can easily become something that has to be avenged. If we could somehow alter this kink of mentality, if we could give women, not a vitamin pill, but a confidence pill, the unalloyed permission to be who they were without the constant fear of critical undermining by others, wouldn’t that make the world a better place? Forget the pill, we could do it if we somehow managed to make women better readers of one another. If they stopped looking for similarity and found in difference some interest, curiosity, learning. When women’s writing erupted into a glorious profusion of different, new, unheard voices back in the 70s, the sisterhood welcomed them all. We lost something vital when we believed we’d reached equality and started bickering over what it should look like.

Isn’t now the perfect moment to understand that each woman is her own story? And that the story is there to be listened to attentively for the pleasure of solidarity and curiosity, not judged for the pleasure of finding it wanting, or the fear that it might reflect badly on our own?