This is the second year where for Women in Translation Month I only read books by women in translation. Last year that was really successful, this year my choices weren’t all quite as strong but there were still some very definite winners.

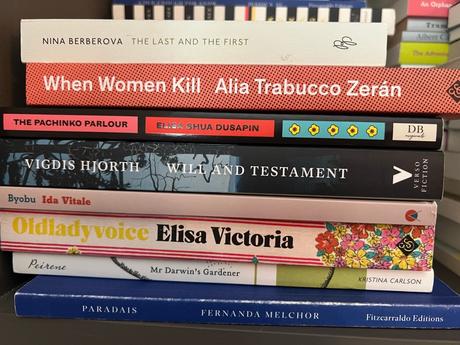

Before we start though, here’s my pile of potential reads. Let’s see which I actually managed…

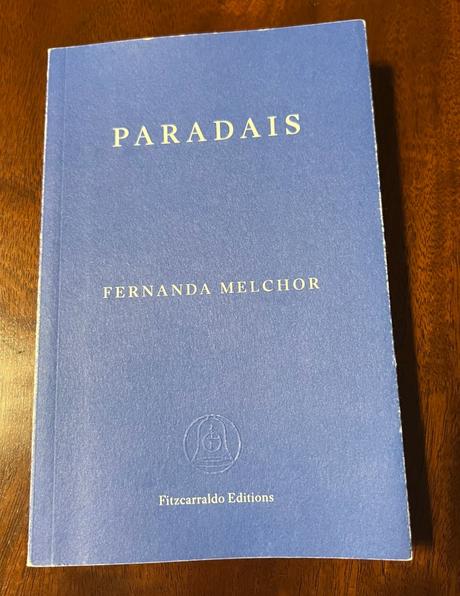

Paradais, by Fernanda Melchior (translated by Sophie Hughes)

It’s hard to go wrong with Fitzcarraldo and Fernanda Melchior has had a lot of attention. Her Hurricane Season didn’t quite appeal, but I’m a sucker for novels in gated communities (or hotels, or boarding houses…).

Polo is a junior gardener on the Paradais estate. Franco is a similarly aged teenage boy who lives on the estate. Polo can buy drink outside the estate and smuggle it in. Franco can pay for it. So they pool resources and regularly get drunk together. All fine until Franco comes up with a plan to address his lust for his attractive neighbor and Polo’s need for money at the same time through a spectacularly poorly planned kidnapping attempt.

It’s well written, of course, and Melchior captures intensity of male adolescence well (I’m not saying female adolescence is any less intense, but having been a male adolescent I thought this extreme but recognisable). That said, this is in places a very ugly book with a lot of sexualised violence and some really brutal scenes. Too much so for me in fact. I’m not denying Melchior’s talent, but I prefer my ugliness leavened a little. Tony wrote a much more positive piece about this here which goes into more detail.

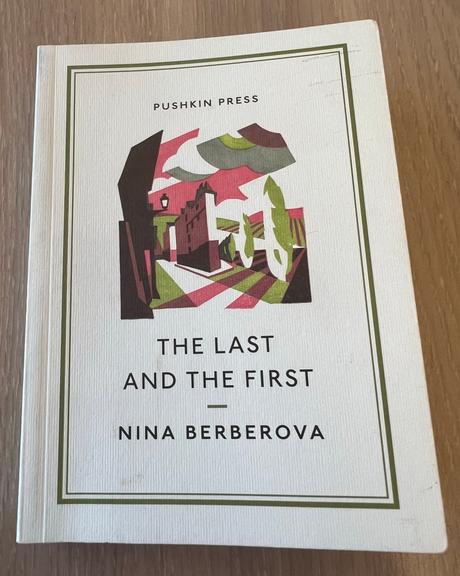

The Last and the First, Nina Berberova (translated by Marian Schwartz)

I’ve enjoyed several of Nina Berberova’s short stories/novellas, but this was my first novel by her. Ilya Stepanovich is a young farmer making his life in Provence. His step-brother Vasya is lured away from the farm to Paris with the promise of a return to Russia. Between them they personify the conflict in each of the Russian emigres between making a new life in France or seeking to preserve the lost Russia of memory.

Berberova always writes well, but I think I prefer her short fiction. The characters here were a bit too emblematic of their respective causes for me and I thought the greater length perhaps led to a loss of the subtle uncertainty I associate with Berberova. This was still a solid read, but I don’t think it’ll be an end of year contender.

Mr Darwin’s Gardener, Kristina Carlson (translated by Emily Jeremiah and Fleur Jeremiah)

This is an interesting one. It’s an exploration of the clash of science and faith told through the lens of the village an elderly Charles Darwin lives in, casting a huge celebrity shadow over the villagers’ ordinary lives.

Darwin himself isn’t a character here, more a prompt for villager reflection. Interestingly Carlson moves the narrative voice between individual characters (such as the eponymous gardener) and a sort of combined community voice. This is particularly well done in a scene with a church congregation, moving from them collectively during the service to their individual voices scattering as they leave.

It’s skilfully done and it manages that tricky task of both being a bit experimental while also highly readable. There’s a lot packed in to a short space here and it’s one I think I may return to in future. Grant wrote well about it here, particularly on the book’s style, and Tony unpacks some of the structure and talks a bit more about the style here (both pick up on that church scene).

Oldladyvoice, by Elisa Victoria (translated by Charlotte Whittle)

Oldladyvoice (great title) is a debut novel set in the ’90s. Nine year-old Marina is the narrator. Like most child narrators she’s precociously clever, but her home situation is unstable. Her mother is seriously, perhaps terminally, ill. Her mother’s boyfriend Domingo is nice but he’s naturally more focused on the mother. That leaves Marina’s grandmother with whom she’s very close.

There’s a strong element here of Marina’s developing sexuality, her longing for a first kiss and fascination with Domingo’s adult comics some of which have breasts in them! There’s a lot too though on the intense importance of making friends and being accepted.

For me the main issue was that the narrative voice just didn’t always persuade me. At times it felt very much like I was reading an adult author, not a nine year old. Sustaining a child voice over the length of a full novel is genuinely hard and Victoria mostly pulls it off, but for me not entirely.

Grant liked this a bit more than me and specifically says “she is far from being a precociously irritating child narrator” (I agree she’s not irritating…). He rightly calls out the joyousness of the book which is perhaps its greatest strength. Despite my reservations it is absolutely packed with life.

Karate Chop, Dorthe Nors (translated by Martin Aitken)

This was published in one volume with Nors’ novella Minna Needs a Rehearsal Space, but I’ve split them out. Karate Chop is a series of generally very brief short stories told in a fairly flat style. They’re enjoyable, but perhaps because of the brevity didn’t stick much in memory. If you’ve read other Nors and liked it you’ll like this (I have and did), but other than that I can’t remember enough to say too much about it. It may be that I’m just not Nors’ reader.

Byobu by Ida Vitale (translated by Sean Manning)

This is another interesting one and very difficult to describe. Byobu is in a sense the central character, but he is a blank with no real personal characteristics to speak of. Each chapter is a short reflection on an often surreal incident in Byobu’s life. It’s packed with references most of which I didn’t get (Vitale is Uruguayan which may have been an issue there) and is less a novel than an exploration of ideas.

WG has written extremely well about this here. She got this far more than I did, seeing that it was something of an everyman story exploring what it’s like to be alive today and taking pleasure in the language. I’d recommend you read her review since honestly this just didn’t connect with me and I struggled to get to the end of its short 85 page length.

Will and Testament, Vigdis Hjorth (translated by Charlotte Barslund)

Now we’re talking! I loved Vigdis Hjorth’s Never Mind the Post Horn (it made my 2021 end of year list). Will and Testament is just as well written but tonally very different.

This is not one I have trouble remembering. When the family patriarch dies the four adult children split over the inheritance. The narrator is long estranged from her parents, but sides with her brother against her two sisters over the apparent favouritism the parents have shown them.

Complicating matters further is the question of why the narrator became estranged (you’ll guess quickly, not least as she refers to Festen a fair bit). Her sisters want to build bridges now the father is gone, but they’re not willing to accept the roots of the narrator’s trauma.

This is properly meaty stuff, with great characterisation and a central family conflict that many of us will recognize. Even without the added complication of the narrator’s childhood the impact of the will on the family dynamic is brutal and believable.

Superb and highly recommended. Caroline wrote about this here and Heavenali here if you’d like more details. Interestingly Heavenali didn’t like it, so its useful to read her piece for a countering view.

The Pachinko Parlour, Elisa Shua Dusapin (translated by Aneesa Abbas Higgins)

Here Dusapin explores intergenerational and intercultural tensions. Claire, a young French-Korean woman, visits her grandparents who own a small pachinko parlour in Japan. She takes on a job teaching French to a local child and plans a trip to Korea for her grandparents who’ve never gone back after fleeting the Korean war.

Claire’s Korean isn’t actually that strong, she’s better in Japanese, but her grandparents despite living in Japan for fifty years or so have never really mastered the language. That’s one reason they may not be really communicating, but far from the only one as Claire puzzles over why her grandparents seem so unengaged with the whole holiday in Korea project…

This is another one I think I’ll return to. It seems slight, but there’s a lot in here. It’s perhaps not quite so strong as Winter in Sokcho (though that could just be because Winter seemed to come from nowhere whereas now we have an idea of Dusapin’s style). Even so, it’s a strong read and the exploration of the gulfs between people is deftly done. Jacqui wrote characteristically well about it here.

When Women Kill, by Alia Trabucco Zerán (translated by Sophie Hughes)

Finally, a bit of non-fiction. I dislike the true crime genre so I only read this because of the author and because I got it on subscription. Then again, I take out book subscriptions precisely so I’ll be exposed to books that I wouldn’t otherwise have chosen.

Zerán explores four Chilean murders committed by women and through them explores larger questions about the role of women in society. It’s interesting, her careful research is evident and the light each of the cases sheds on Chilean society is fascinating.

Despite all that, I wasn’t wholly persuaded by the overall thesis. At one point Zerán comments that the press only take photos of the women on their way to or from court or prison. She takes this as a sign of society’s wish to whisk them out of sight, but surely it’s simply that it’s the only time their pictures can be taken? It felt to me more a practical issue than a sociological one.

To be fair to Zerán she escapes the usual challenge in true crime of an air of prurience because her goal here clearly isn’t simply to entertain. For me though it remains a genre I struggle with. One can impose meaning on these events, but each one is so particular on its facts that I’m not sure how much they really tell us about anything other than that people sometimes kill and sometimes they have reasons we can understand and sometimes not.

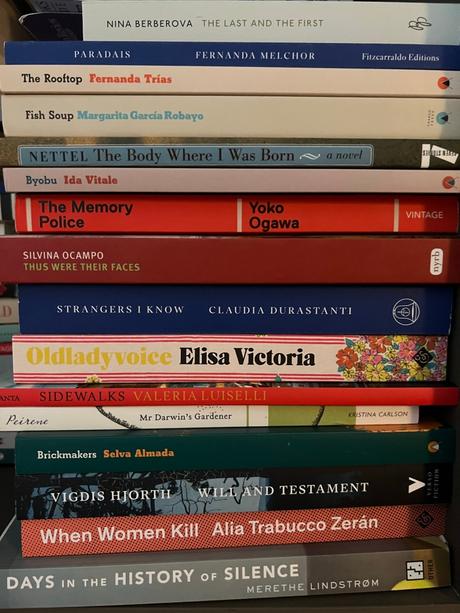

And that’s it! Here’s my photo of the final stack I read (minus the Nors as I read that on Kindle). Not bad and thanks again to #WiTMonth for encouraging me to broaden out my reading a bit.