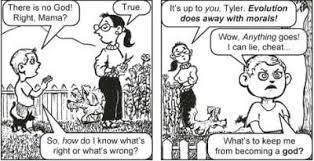

My wife and I have been reading, aloud to each other, The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky’s 1880 novel. A key motif is whether “without God everything is permitted.” That’s become a major talking point against atheism; the notion that atheists have no reason to be moral. Indeed, the idea’s societal reverberations may well be traceable back to Karamazov.

My wife and I have been reading, aloud to each other, The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky’s 1880 novel. A key motif is whether “without God everything is permitted.” That’s become a major talking point against atheism; the notion that atheists have no reason to be moral. Indeed, the idea’s societal reverberations may well be traceable back to Karamazov.

It was written when atheism was beginning to be important. Nietzsche soon declared, “God is dead.” Dostoevsky was himself deeply religious, yet in Karamazov he does not cavalierly dismiss the opposing point of view. Rather, he wrestles with the moral implications.

I have previously discussed morality without God. If we need him for morality, we’d be in trouble, because of course he’s a fiction. But in truth, whatever moral codes religions prescribe, they are merely a reflection of our pre-existing moral intuitions, rooted in evolution. Our ancestors lived in groups wherein cooperation, morality, and even altruism aided survival. People with tendencies toward those virtues lived to pass along their genes. These norms became further embedded through culture; religions are cultural inventions and again merely incorporate the moral ideas already a part of a given culture.

In Karamazov, Ivan hallucinates a conversation with the Devil. And in it, the Devil makes this remarkable speech — imagining what he thinks Ivan himself would say:

“Once every member of the human race discards the idea of God (and I believe that such an era will come, like some new geological age), the old world-view will collapse by itself without recourse to cannibalism . . . . Men will unite in their efforts to get everything out of life that it can offer them, but only for joy and happiness in this world. Man will be exalted spiritually with a divine, titanic pride and the man-god will come into being. Extending his conquest over nature beyond all bounds through his will and his science, man will constantly experience such great joy that it will replace for him his former anticipation of the pleasures that await him in heaven. Everyone will know that he is mortal, and will accept his death with calm and dignity, like a god. He will understand, out of sheer pride, that there is no point in protesting that life lasts only a fleeting moment, and he will love his brother man without expecting any reward for it. Love will satisfy only a moment in life, but the very awareness of its momentary nature will concentrate its flames, which before were diffused and made pale by the anticipation of eternal life beyond the grave . . . And so on and so forth. Very sweet!”

In the next passage the Devil invokes twice the “everything is permitted” trope — the new “man-god” can “jump without scruple over every barrier of the old moral code devised for the man-slave.”