Here we see a shepherd on a harsh stretch of land, standing next to an odd pair of white dogs—one crouched, the other with an half-open mouth, spitting out countless hours under the blazing sun—and leaning on a slender stick that is held up by the right hand just in front of his clumsily sewn uniform of goat skin. It’s the oldest picture of such a scene in Maremma, the marshy swamp in the South of Tuscany, I’ve managed to obtain. The man gazes intently (or else sunken into sleep) through the lens, while the two dogs look away, their hair so obviously trimmed and unruffled to look like stuffed pets. This is clearly an uneventful moment in their unremarkable lives. Yet the image has a wounded, almost desperate look, like an old-time circus bear working his way from village to village, earning money for his masters and food for himself.

The shepherd is an older man, on the tall side, a simple, obedient peasant, perhaps, wearing an oversized stitched blanket that makes him look comical and choked up—trousers rumpled like an accordion, a tattered Fedora cap tilted over protruding ears, the color almost as black as the dust that has been trudging down the goat skins on his shoulders. He could be an amusing figure, reminiscent of the good soldier Švejk in Jaroslav Hašek’s satirical novel, if it wasn’t for the scene’s pale, murderous, scorching atmosphere that reminds us, instead, of a place of public execution in Teheran. The shepherd is not silent because of the ruthlessness of his job, but because finally he has nothing to talk about. From grandfather to grandfather, his people would sit down in the shade to eat, march, and sleep on the clay floor back with lizards and locusts eagerly popping out. At times, he has been excruciatingly hungry, without allowing himself to perish under thirst or exhaustion. As evenings draw near in the hut, if such a shepherd had met the young Alberigo Evani, who must have looked shyly and haggard even in childhood, he would presumably have scratched his head; but Evani’s parents in Massa Carrara were aware of his innate quality, evenly split between intelligence and sadness. When they sent him over to Milan for training in 1978, and he stood on tiptoe over a carpet of black caracul, they whispered, “Chicco, you are a man of great possibilities.”

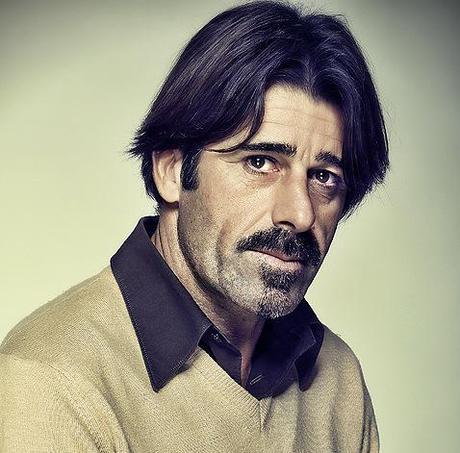

(Photograph: Marco Ciofalo)

Whoever scrutinizes this mature portrait of Alberigo Evani, taken when he was forty-seven, will understand a lot. The contrast between this photograph and his younger image as a winger of AC Milan and Sampdoria is striking in every respect. The huge, powerful patriarch-like head stands sulkily, peremptorily, goatee on his lips, black waves of hair over his sideburns, and beside that the small pale boy, frail, nervous, obediently standing at attention, barely reaching his opposite full-back’s shoulders. His face is neither sad nor poor, neither improper nor apathetic; yet his expression is not meant to cheer us, is meant to remind us of how much solitude is stitched the very fabric of a winger’s job.

Evani was not a nomadic player. He settled permanently—his career nothing but one large punitive expedition that turned vast regions into inhabited footballing land. A lot of blood flowed. Ancient, slumbering, loafing Italy trembled to its foundations, as Arrigo Sacchi began creating an imposing army of zonal marking. Simple, short men like Donadoni were given uniforms and guns. The army was the apple of the Shah’s eye, his great passion. The army must always have money. It must have everything. The army will make the nation modern, disciplined, obedient. Everyone would have Mediolanum stocks. Evani’s companion on the wing was Angelo Colombo, a blonde-haired lad who had been raised in a Lombard dungeon for years and never managed to raise his voice in complaint. Sacchi had entrusted him with the preaching of a critical sermon, and so he entered the pitch like an ayatollah in the mosque, pummeling the critics with a cane. Alberigo grew timourous of Colombo’s cruel, outlandish exhaustion. (In a few months, the blonde winger gave out everything he had, and his lungs became like deserted quarters of a city where everybody disappeared except the exultant crowd in the stadium terraces.) Evani remained useful yet reluctant, as if he knew that the Empire gives, and the Empire takes away.

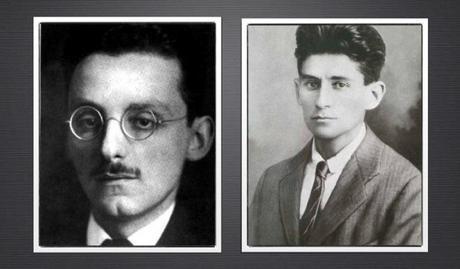

Evani’s unspeakable solitude can be adequately compared only to the membranaceous sadness of some French daguerreotypes from the Napoleonic era, to the little hunting-castle of Eckhartsau, or, better still, to the sorrowful, neighboring features of Max Brod and Franz Kafka. Evani’s eyes are defenceless and inextricably rich, like those of a merciful detective; his ears, a straightforward case-study of hypoacoustic receptivity. Brod and Kafka, on the other hand, as their eyes meet ours for an instant over that dusty register of Mitteleuropean time, look like two different versions of a dying Everyman who instead of parading in medieval streets is simply awaiting acceptance in an Alpine sanatorium—for a word of pietas, a disenchanted friendship, or a temperature chart. Evani’s career is a Talmudic odyssey that dances almost to the point of death and ultimately teaches us how to become a man. The late Kafka admitted that without Dora he would be nothing, accpeting his own weakness, giving himself to love; Alberigo learnt that much, if not before, in the unyielding fields of Tuscany, during that memorable, silent training in which Sacchi ordered his Milan players to waltz and swirl around their respective positions in the field without the ball. (The great Butragueño, who came to spy on the training camp, must have thought that, truly, what he was scanning were the inmates of the Wienerwald sanatorium, all with a corporeal temperature of 38.5o.) Judaism and the adventures of writing take no part in the story of Evani the winger, but as Franz Kafka says, his life too concerns the man whose Hebrew name is Amshel. ♦