Asked to name my favorite author, I’d probably say Faulkner. I’m reminded of this by finding, at a recent book sale, his novel Sartoris. I’d always meant to read that one – since I happen to be a three-time recipient of the Sartoris medal.*

Asked to name my favorite author, I’d probably say Faulkner. I’m reminded of this by finding, at a recent book sale, his novel Sartoris. I’d always meant to read that one – since I happen to be a three-time recipient of the Sartoris medal.*

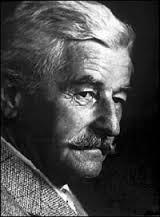

Faulkner’s work is not easy reading, but worth the effort. It always packs a wallop, plumbing the greatest intensity of human experience.

Faulkner

Its difficulty is exemplified by The Sound and the Fury, whose beginning seems like gibberish. Once when I took my teenaged daughter to a bookstore, she picked it out and asked me about the title. I replied that it’s from Shakespeare: a human life is like “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” Not till I said that did I suddenly grasp the title’s full import. The book is – literally – “a tale told by an idiot.”

In this and other Faulkner books it’s not always obvious what’s being talked about. You have to work at it and keep reading.

Faulkner’s oeuvre is set in his own deep South, from around the mid-1800s to the early 1900s; and focuses on its white society. It’s not a pretty picture. Every negative aspect of the human character is unsparingly portrayed.

Now, I am not a cynical misanthrope, and hate misanthropic books. But Faulkner is no misanthrope either. To the contrary: while he does depict all the awfulness of the human animal, he does it with sympathy. His message is not: despise him, condemn him. Rather it is: understand him. And when I wrote my Optimism book, it was a quote from Faulkner that I chose for its epigraph: I believe that man will not merely endure; he will prevail.

Still, when I read these books, they make me very glad I didn’t have to live in their time and place – even as a white person. The palpable change fuels my optimism. I see the past as dark, and my own time and place as full of light. We have progressed.

Faulkner’s books tend to entail peeling back layers to finally get to the heart of things. This is nowhere truer than in Absalom, Absalom!

(Spoiler alert: stop here if you want to read the book.)

Thomas opposes the match. He has an excellent reason: it develops that Charles is already married. But, as we eventually learn, that’s not the true reason. It seems the other wife is not an insurmountable obstacle.

However, by and by, a more devastating fact about Charles emerges: he’s actually Thomas’s son, by his own previous Haitian wife.

Incest would seem an amply good reason to oppose the marriage. But, it turns out, that wasn’t the true reason either; for Thomas, a rough character, not even that is an insurmountable obstacle.

This ends badly, for everybody. The lone survivor, decades later, is Charles’s black grandchild – another idiot.

Reading Faulkner makes me better appreciate my own life and family.

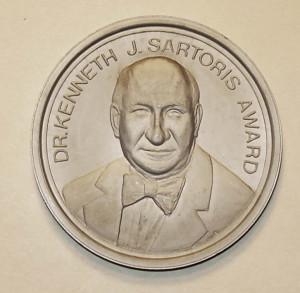

* Awarded by the Albany Numismatic Society, named after a different Sartoris.