Book Review by Chris Hopkins.

I know we were meant to be reading a Richmal Crompton book for adult readers, but I couldn’t resist the treat of reading a Just William at the same time, so am going to justify this (to myself anyway) by saying that I wanted to compare a Just William and a grown-up Richmal Crompton from the same year. In fact, I didn’t quite succeed in that, but at least they are both nineteen-forties / wartime books.

I enjoyed reading both very much, though in the end I have a reservation about Weatherley Parade – and none about William Does His Bit. I somehow started by reading the Just William first, so I shall write about that first. William Does His Bit is, of course, set in the usual Brown family world in many respects – Mr Brown is generally as impatient of William’s foibles as usual, as are Robert and Ethel, his older brother and sister, while Mrs Brown is somehow more patient but not necessarily fully in tune with William’s inner world. In other respects, though, this wartime world is, of course, in no way normal, and that is both a problem and an opportunity for William. He always lives in a world of heightened colour, the drama of which is in some ways met by the war on the home front and in other ways consistently disappointed. Thus, alas, as we are told in the title story, ‘William Does His Bit’:

William was finding the war a bit dull. Such possibilities as the black-out and other war conditions afforded had been explored to the full and were beginning to pall. He had dug for victory with such mistaken zeal – pulling up as weeds whole young rows of young lettuces and cabbages – that he had been forbidden to touch fork or hoe again. He had offered himself at a recruiting office in Hadley … He next wrote to the Premier to offer his services as a spy, but received no answer … He had almost given up hope of being allowed to make any appreciable contribution to his country’s cause when he heard his family discussing an individual called ‘Quisling’ who apparently and in a most mysterious fashion existed simultaneously in at least a dozen places. (Macmillan Children’s Books edition, 1988, p.2).

The traitor is soon transformed by William’s inattention to detail and imagination into Grisling and then ‘Ole Grissel’. William reckons that if Grissel is everywhere, then he must be hiding somewhere in either his own or a neighbouring village. William is sure that Grissel is his chance to help his country and also the solution to his disappointment with the war so far.

William does not have to search too long before finding his first clue to the whereabouts of Grissel and the gang which William has by this time added to the story. A very ordinary-looking woman walking by asks another woman what the codeword of the day is. He follows the pair to a school, naturally empty during the summer holidays. His worst hopes and fears are realised. Eavesdropping through an open window, he hears and sees a group of people masquerading as English civilians under the supervision of a rather insignificant looking man, who does not at all meet William’s expectation of a spy chief. They are all poring over maps and in full sight planning the destruction of Hadley, Marleigh and Upper Marleigh:

He could even see the road marked where his own home was. Going to hand over his own home to ole Hitler they were …with Jumble and his pet mice and his collection of caterpillars and his new cricket bat. The idea of this infuriated him even more than any of the previous German outrages (p.10).

The man in charge is clearly Grissel himself, despite appearances. Next, William hears one of the women on the phone reporting terrible damage to the neighbourhood – a crashed plane, houses on fire and collapsing, even the police station blown to pieces (p.10). But William has just walked through the streets referred to and knows that none of the reports are true. He knows what is happening:

‘All lay peaceful and intact in the summer sunshine, while this gang of Grissel confederates were broadcasting these outrageous lies. Propaganda … same as old Gobbles’.

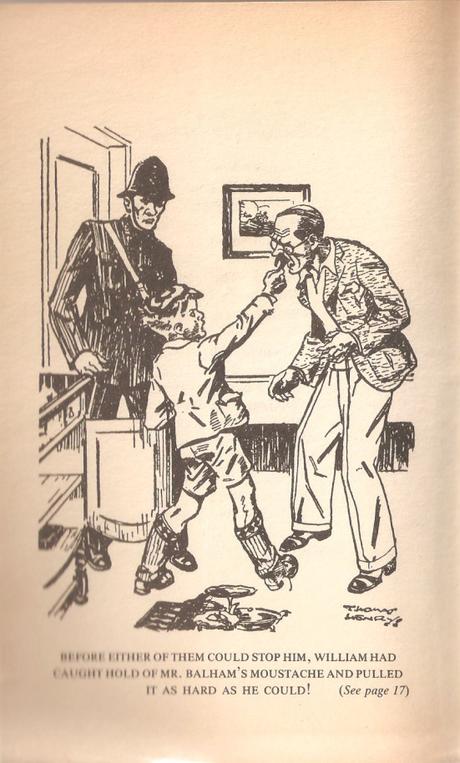

William takes action of course and after some complications he triumphantly prepares to prove to the police officer he has summoned that ‘ole Grissel’ is a spy by pulling hard on his obviously fake moustache (see Thomas Henry’s wonderful drawing below). As it turns out, Mr Balham, Supervisor of the Marleigh A.R.P. Report Centre, is very attached to his entirely natural facial hair, and his fury only abates when William has told his whole story to the policeman. William has of course overheard a Civil Defence exercise in which the ARP was rehearsing for a serious raid on the local area. Being a Just William story, there is an unexpected happy ending:

Mr Balham was an extremely patriotic little man and he felt that William’s zeal, though mistaken, was on the whole commendable. After dismissing the policeman, he had refreshed William with a large currant bun and a glass of lemonade and finally presented him with half a crown. Against his will, William had been persuaded of the innocence of his host. He was reluctant to abandon the carefully built-up case against him, but the currant bun and lemonade and half-crown consoled him. (pp.18-19).

(Sometime before decimalisation, I used to get half-a-crown pocket-money a week, so that struck a chord!). Mrs Brown asks William about his day, but naturally does not believe a word of ‘her son’s fantastic imaginary adventures.’

The story is characteristic of the ten in the volume. The disappointments and contra-temps of everyday life need the constant compensation of William’s absolute faith in his own reading of things, and that is surely as true for William’s readers as it is for William. At the end of nearly every story, reality has been adjusted into something much less dull, much more satisfactory, than it was before William’s inspired and innocent (?) intervention. I could joyfully give an account of how the remaining nine stories deal with the fictions and realities of wartime England, but of course it is much better for you to read them yourselves.

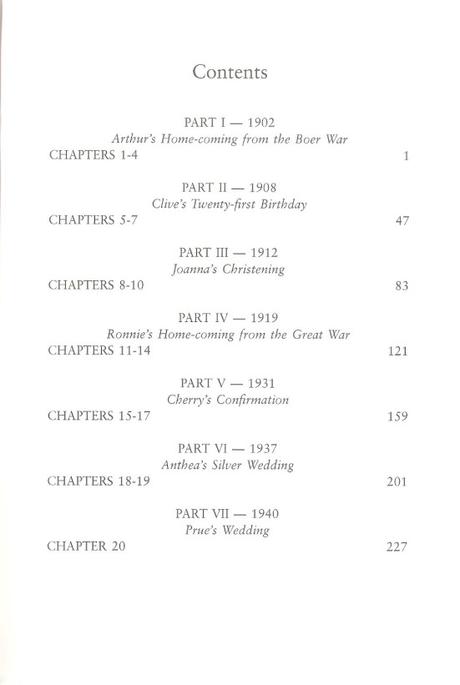

I had not read any of Richmal Crompton’s novels for adults before, so Weatherley Parade was a new experience. The novel covers the period from 1902 to 1940, and is the story of several generations of the Weatherly family and their near neighbours. It is carefully structured round two different kinds of marker of time: Britain’s wars of the twentieth-century, and significant family events.

In fact, from the Part headings, the pattern does not seem quite complete. Part I refers to the Boer War and Part IV refers to the Great War (1914-1918). Parts II and III refer to a birthday and a christening, while Parts V and VI refer to a confirmation and a silver wedding. Part VII might be expected to close the frame with a reference to the ongoing Second World War, but instead refers to another personal event: Prue’s Wedding. I’ll return to this.

I was very much absorbed by the novel’s characters and moved by its sustained melancholy. For though the Weatherley family over the generations has a variety of experiences, including marriages lasting and successful as well as short and painful, deaths premature and after long life, happy and unhappy childhoods, there is a sustained sense of the sad complexity of life and of some lives not fulfilled. Sometimes, this is as a result of the wars which involve Britain, as the structure might suggest, but is also often to do with individual character and experiences. In the case of Major Arthur Weatherley, whose home-coming opens the novel (though significantly we meet his children before we meet him), the rest of his life does seem something of an anti-climax. His children remember a fine military figure, but he returns from South Africa having suffered badly from enteric fever and his uniform now hangs loosely on his body. He never recovers from this, and for the remainder of the novel until his death in 1931 the household is organised round not disturbing him. He has left the army, does not need to work for a living, and seems to have no ambitions beyond being quiet. Of course, that is perfectly credible – many war veterans never did /never do fully recover from wounds physical or mental – but the novel, while highly consistent in avoiding explicit comment on characters, does let us see that other characters experience him as a passive, deadening presence who constrains his wife and children for many years. Soon he grows fretful if his wife Helena is not by his side at all times, preferably in the library, the room reserved for his quiet use (though not for purposeful reading particularly). Other members of the family point out to Helena that she has become a full-time ministering angel and she agrees that she has, but see no other possibilities for herself. After Arthur’s death, Helena herself declines rapidly with no sense of remaining purpose, and soon dies.

That environment influences the next generation’s choices in various ways, but is not the only factor. There is the son Clive, who when Arthur is away at the Boer War, takes on the role of ‘the man of the house’ as a teenager and always does his duty without any lapses. He is an intriguing character who is perfect at his role, yet has no depths, no interiority at all. Indeed, many other characters dislike him (as I increasingly did as the novel went on). Even his father dislikes him, wishing he would do something wrong from time to time. Clive becomes a teacher (at a private school, of course) and is utterly upright and inflexible and deeply unpopular with boys and colleagues. His headmaster tries but fails to make him more human and humane. He marries and that too becomes a disaster because of his inflexibility and insistence on treating both wife and little daughter as pupils at all times – till wife and daughter run away, with further sad consequences.

His younger sister Anthea has seen her future from an early age as one where she will have a star role – as an actress or an artist. In fact, once grown-up marriage seems her only way of escape, but the handsome dashing and unreliable young man she wants to marry her never asks, and far from taking up any career, she ends up marrying the unexceptional, dull but wholly reliable Jim, who does everything that a good husband should throughout their long marriage (and actually seems a better choice). Anthea suppresses any disappointment and plays the long-term role of wife and mother apparently without any thoughts about anything else (though she does construct these as starring roles at all times). And so on across the generations, each with the dynamics of its relationship to parents, spouses, children and grand-children lovingly traced. As with William’s early wartime adventures, I will not take the reader through the narratives of every densely-textured generation, but hope these examples from early in the novel gives a sense of its interests. Essentially, I think it asks highly-nuanced questions about the relationships between individual character, family, and wider historical environments (the typical territory of the novel form), with a particular if always home-front emphasis on the three modern wars of its time-frame.

Finally, to come back to my reservation about the novel, which is indeed bound up with how it handles the relationships between history, character and meaning in one specific but important element of its plot: the ending. The ending to this historical overview of the twentieth century is surely what completes (if only provisionally) the novel’s pattern by providing a viewpoint, a perspective from which to make sense of the thirty-eight years of experience recounted. The novel shows itself fully aware of this narrative need, but I was not sure I was satisfied by what it provides. Here are parts of the last two pages:

On the terrace, Anthea was recalling memories of her youth.

‘We had a marvelous time on Clive’s twenty-first birthday … mine wasn’t half so exciting, because Father was having one of his bad attacks…’

…

Jo [her second daughter] turned to her.

‘I was seeing old Father Time as a sort of watchman with a bell going round this house and calling out, ‘Arthur’s homecoming and all’s well’…’Jo’s christening and all’s well’… ‘Clive’s twenty-first birthday and all’s well’… [all ellipses as in the text in this quotation].

‘But what about 1940?’ said Anthea with a sigh.

Jo smiled.

‘1940?’ she said, ‘1940 and all’s well’ (pp. 243-4).

Here Anthea and Jo in effect allude to and reinforce the structure of the novel in which they appear, by explicitly looking back at the key device of family events marking the passage of time. They even identify as key moments for the family the events which appear in the Contents list (normally considered paratextual – that is to say outside the text proper of the novel itself – and therefore conventionally beyond the knowledge of the characters). That is not a problem, but it is the treatment of 1940 as the point of completion, or viewing-point, which bothers me a little. Jo, who is working as an ambulance driver in London, refers during the ‘Prue’s Wedding’ section to her experiences during the London Blitz, which is clearly ongoing, and so this part of the novel must be set in or after September 1940, when the Blitz began (p. 229). There were things for the British to be cheerful about around this time, especially that the Battle of Britain was won, and without German air superiority the likelihood of an invasion of the British mainland diminished. However, to declare that all is well and select late 1940 as a stable and wholly optimistic viewing-point seems to go too far. The majority of Europe has been occupied by Nazi forces, U-boats were sinking an enormous tonnage of merchant ships in the Atlantic, there are significant civilian casualties from the bombing, rationing is in force, and British and Commonwealth forces were heavily engaged (with some successes) against the Italian Army in North Africa. I am not sure what understanding of the twentieth century so far this end-point as presented in the novel gives us. It could be that the Battle of Britain is the key event, signified by the family event of Prue’s wedding to her fighter pilot (who tells her that much as he loves her, ‘flying’s got to come first’, p. 232). Maybe this is why a family event marker replaces the expected war marker in the Contents pattern – by nineteen-forty, the personal is the political as total war involves the whole population, and Prue, herself working as a welfare worker in a North London factory, in marrying an RAF fighter pilot is a participant in both parts of the pattern. Overall, the final words of the novel seem to try to wrap things up too neatly and too insubstantially, but actually do not fit with the complexity and uncertainty of the relationships between individuals and history which the body of the novel has so successfully portrayed. Perhaps a more open-ended close, looking forward into a world of great uncertainty would have been better?

I did very much enjoy Weatherley Parade and would recommend it, and will certainly read more of Crompton’s novels for adults. However, it seems odd that the writer who could plot and end every Just William story so perfectly has trouble (in my view) completing the architecture of this novel (admittedly at a very tricky point in history for the novelist). I was very struck by the overall differences in tone and mood between the worlds of Just William and the Weatherleys, but just occasionally there was some shared ground. Thus, there is Clive’s younger (and happier) brother who is pictured in 1908 in his own private world:

Billy, a slender long-legged boy of nine, came running round the side of the house, took cover for a moment behind a variegated laurel, darted out again, fired an imaginary pistol at an imaginary pursuer, leapt down the terrace steps, four steps at a time, threw off his pursuers by dodging round the cedar tree, then, keeping warily in the shelter of the bushes, made his way to the summer house, where the mysterious X, cloaked and masked, awaited the secret document he carried (p.49).

Just William Does his Bit was slightly better for my morale in this latter-day national and international crisis, but both books were thoroughly intriguing.