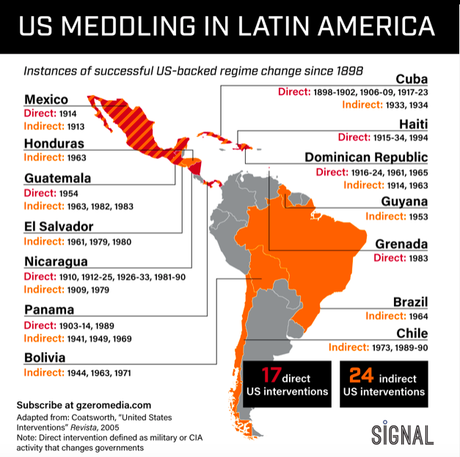

(The map above is from gzeromedia.com.)

(The map above is from gzeromedia.com.)Donald Trump has refused to take a military intervention of Venezuela off the table. And it wouldn't surprise me a bit if he invaded that country. Things are not going well for him in the United States, and he might just think a war is just what he needs to solve his domestic problem.

He has tried to frame Venezuela's current problems as supporting democracy. But the truth is that he is supporting an attempted coup that tried to unseat an elected leader (and undoubtably, that attested coup was probably arranged, or. at least supported by our own CIA).

It wouldn't be the first time the United States has overthrown a Latin American government. Since 1898, the U.S. has done it at least 41 times (and that doesn't count the number of times we tried and failed, like the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba). We have a long history of meddling in Latin America.

The myth that most Americans want to believe is that the U.S. did that to spread democracy or defend human rights. That is a lie! Many of the governments we overthrew were democratically-elected, and none of the meddling was to support human rights. Most of the time it was done on behalf of American corporations -- when the leader of a country got the crazy idea that his country's resources belong to the people of that country, and not a foreign (U.S.) corporation.

Below is part of an excellent article by John H. Coatsworth for the Harvard Review of Latin America:

In the slightly less than a hundred years from 1898 to 1994, the U.S. government has intervened successfully to change governments in Latin America a total of at least 41 times. That amounts to once every 28 months for an entire century (see table). Direct intervention occurred in 17 of the 41 cases. These incidents involved the use of U.S. military forces, intelligence agents or local citizens employed by U.S. government agencies. In another 24 cases, the U.S. government played an indirect role. That is, local actors played the principal roles, but either would not have acted or would not have succeeded without encouragement from the U.S. government. While direct interventions are easily identified and copiously documented, identifying indirect interventions requires an exercise in historical judgment. The list of 41 includes only cases where, in the author’s judgment, the incumbent government would likely have survived in the absence of U.S. hostility. The list ranges from obvious cases to close calls. An example of an obvious case is the decision, made in the Oval Office in January 1963, to incite the Guatemalan army to overthrow the (dubiously) elected government of Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes in order to prevent an open competitive election that might have been won by left-leaning former President Juan José Arévalo. A less obvious case is that of the Chilean military coup against the government of President Salvador Allende on September 11, 1973. The Allende government had plenty of domestic opponents eager to see it deposed. It is included in this list because U.S. opposition to a coup (rather than encouragement) would most likely have enabled Allende to continue in office until new elections. The 41 cases do not include incidents in which the United States sought to depose a Latin American government, but failed in the attempt. The most famous such case was the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of April 1961. Also absent from the list are numerous cases in which the U.S. government acted decisively to forestall a coup d’etat or otherwise protect an incumbent regime from being overthrown. Overthrowing governments in Latin America has never been exactly routine for the United States. However, the option to depose a sitting government has appeared on the U.S. president’s desk with remarkable frequency over the past century. It is no doubt still there, though the frequency with which the U.S. president has used this option has fallen rapidly since the end of the Cold War. Though one may quibble about cases, the big debates—both in the public and among historians and social scientists—have centered on motives and causes. In nearly every case, U.S. officials cited U.S. security interests, either as determinative or as a principal motivation. With hindsight, it is now possible to dismiss most these claims as implausible. In many cases, they were understood as necessary for generating public and congressional support, but not taken seriously by the key decision makers. The United States did not face a significant military threat from Latin America at any time in the 20th century. Even in the October 1962 missile crisis, the Pentagon did not believe that the installation of Soviet missiles in Cuba altered the global balance of nuclear terror. It is unlikely that any significant threat would have materialized if the 41 governments deposed by the United States had remained in office until voted out or overturned without U.S. help. In both the United States and Latin America, economic interests are often seen as the underlying cause of U.S. interventions. This hypothesis has two variants. One cites corruption and the other blames capitalism. The corruption hypothesis contends that U.S. officials order interventions to protect U.S. corporations. The best evidence for this version comes from the decision to depose the elected government of Guatemala in 1954. Except for President Dwight Eisenhower, every significant decision maker in this case had a family, business or professional tie to the United Fruit Company, whose interests were adversely affected by an agrarian reform and other policies of the incumbent government. Nonetheless, in this as in every other case involving U.S. corporate interests, the U.S. government would probably not have resorted to intervention in the absence of other concerns. The capitalism hypothesis is a bit more sophisticated. It holds that the United States intervened not to save individual companies but to save the private enterprise system, thus benefiting all U.S. (and Latin American) companies with a stake in the region. This is a more plausible argument, based on repeated declarations by U.S. officials who seldom missed an opportunity to praise free enterprise. However, capitalism was not at risk in the overwhelming majority of U.S. interventions, perhaps even in none of them. So this ideological preference, while real, does not help explain why the United States intervened. U.S. officials have also expressed a preference for democratic regimes, but ordered interventions to overthrow elected governments more often than to restore democracy in Latin America. Thus, this preference also fails to carry much explanatory power.