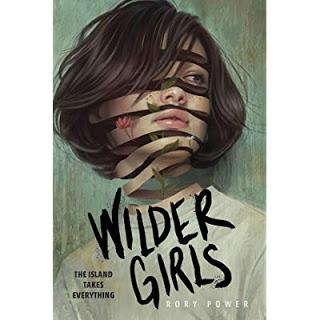

In Rory Power's Wilder Girls, a mysterious illness ominously named the Tox has taken hold on an isolated island which hosts Raxter, an all-girls school. For eighteen months, the infection has turned the girls' bodies inside out, changing them horribly, adding organs and bones, transforming them into new forms, sometimes too far to sustain life. Hetty, one of the main protagonists, voices the idea that the Tox is attempting to improve the bodies it inhabits, but that the bodies are not able to take it - an illness that is pushing the boundaries beyond what the girls can take. It's a familiar idea, because it resembles what happens in Jeff VanderMeer's Southern Reach trilogy - but Wilder Girls is amazing, and perhaps one of the best novels written this year, precisely for applying this concept to teenage girls, and telling a haunting stories specifically about these teenagers fighting to tell their own stories.

In Rory Power's Wilder Girls, a mysterious illness ominously named the Tox has taken hold on an isolated island which hosts Raxter, an all-girls school. For eighteen months, the infection has turned the girls' bodies inside out, changing them horribly, adding organs and bones, transforming them into new forms, sometimes too far to sustain life. Hetty, one of the main protagonists, voices the idea that the Tox is attempting to improve the bodies it inhabits, but that the bodies are not able to take it - an illness that is pushing the boundaries beyond what the girls can take. It's a familiar idea, because it resembles what happens in Jeff VanderMeer's Southern Reach trilogy - but Wilder Girls is amazing, and perhaps one of the best novels written this year, precisely for applying this concept to teenage girls, and telling a haunting stories specifically about these teenagers fighting to tell their own stories. The Tox resembles what happens in VanderMeer's Area X because it transforms what it finds into new forms, creating beautiful but horrible new life from the blueprint of nature and humanity. The idea lends itself to a story about teenage girls because there is already such a wealth of thought on the inherent horror of being a teenage girl - the radical transformation, physically and mentally, from childhood to adulthood, and the perception of society of that change. From how Hetty describes Raxter even before the Tox break-out, it becomes obvious how tightly monitored and policed these female bodies are at the point of transformation (repeatedly, Hetty mentions how much stock the headmistress puts into manners, the rules and regulations of living in a boarding school, the hierarchy that affects everyone). Like in Ginger Snaps, the ultimate reference for teenage girl body horror, the transformation the Tox causes is a metaphor for all the ways in which teenage girls are tightly policed by society because of an inherent distrust in female self-determination. The grotesque biological changes the Tox causes - Hetty feels something growing behind an eye, Reese's arm has grown scales, Byatt, in a horrible transformation we become witness to, acquires a voice horrible both to herself and anyone who hears it - don't work as weapons turned outwards the way that becoming a werewolf does in Ginger Snaps, but Power is clear that the Tox works differently on teenage girls than it does on adults, that there is a clear connection between the Tox' changing of female bodies and female puberty. The older teachers at Raxter simply die of it before they are changed, and the sole man on the island, Reese's father, acquires an incomprehensible aggressiveness and inhumanity that puts him well beyond the ability to still exist in human society.

Equally, as the novel progresses, the Tox is not the enemy that the girls are fighting, it is the adult human reaction to its existence. What puts the girls at danger isn't just their transformation, which is beyond control or help, it is the quarantine that is exercises on the island, the attempts by a military organisation to conduct research into the illness that doesn't value the individual life of the girls. In Wilder Girls, the true villains - the only comprehensible ones, are the adults that put the girls' life in danger, or act selfishly, or refuse to see them as something to be saved rather than something to be studied. It's an interesting statement to make in a story that is essentially about a radical, life-threatening change facilitated by human-created climate change - the adults have no answers, and they cannot be trusted.

An even more interesting point here is perhaps in another contrast with Annihilation - which is both in its book and its film-form the story of one woman, confronted with the horrors of Area X, but defined (both as the biologist in the film and as Ghost Bird in the book trilogy) by her solitude and aloneness. In Wilder Girls, the story is driven by the complex relationship between the three girls at its centre, Hetty and Byatt (the exchanging narrators) and Reese, who circle around each other in configurations much more difficult than just friendship. Hetty and Byatt are best friends, and Reese has always been an outsider, different because her father (the sole male inhabitant of the island when the Tox hits) is the care-taker on the island. When Byatt disappears into the scientific nightmare-maze of the military reaction to the Tox, Hetty sets out to find her, but relies on Reese, who is grieving the loss of her father. These two are connected by a complicated attraction that is made even more multi-layered by Hetty's friendship with Byatt, and Reese's perceived outsider-ness. While Byatt fights for survival, Hetty and Reese have to confront the fact that the sole adult survivor of the Tox cares nothing for the safety of the girls in her care (the headmistress is ready to sacrifice everyone for her own safety), and that the people presumed to work on a cure have given up on the conveniently geographically isolated area. The only thing that prevails here is the love between the three girls, and their unwillingness to ever compromise each others' survival.