“…from time to time we need to ‘rewild’ ourselves,” says Vajragupta, and he shares his encounters with wild creatures and wild landscapes in an enchanting way, making us feel we’ve entered a secret world with him.

“…from time to time we need to ‘rewild’ ourselves,” says Vajragupta, and he shares his encounters with wild creatures and wild landscapes in an enchanting way, making us feel we’ve entered a secret world with him.

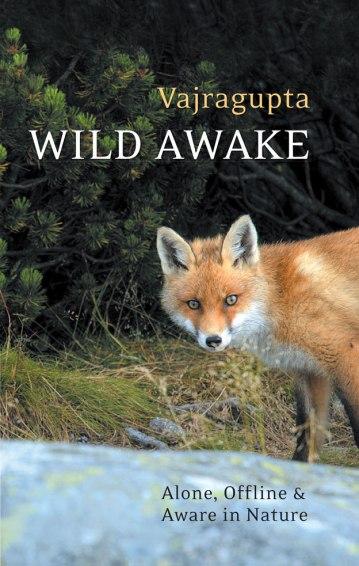

Wild Awake: Alone, Offline & Aware in Nature will make you want to follow Vajragupta’s example of using solitary retreats in nature to become more “fully awake,” more like the Buddha, a name which means “one who is awake.”

What are the benefits of being more fully awake? Perhaps you’ll find it easier to meditate, to get in touch with your soul, to make the right choices for your life. In solitary retreat, as Vajragupta describes, you are better able, in the silence. to hear your truth and know the solutions.

“Places, perhaps especially wild places, can talk to us; they can be full of suggestion and meaning. Inner and outer worlds can mirror each other, and this changes our awareness.”

It’s easy to understand how being out in nature stimulates and nourishes your soul, as Vajragupta describes his 25 years of taking solitary retreats. For those who have questions about how to get the most out of such retreats, he provides an A to Z guide with practical advice and suggestions for designing your own.

Read Wild Awake: Alone, Offline & Aware in Nature for inspiration, then get out there as often as possible!

Thanks to author and Buddhist teacher Vajragupta, who answers my questions here…

AUTHOR INTERVIEW QUESTIONS WITH VAJRAGUPTA

What would you like readers to take away from the experiences you shared in Wild Awake?

I would love it if the book encouraged more people to try out solitude in nature. Some people take to this quite easily. For others, solitude can seem more daunting or challenging. Fear and trepidation can put us off. In solitude we are going to meet ourselves fully and deeply. And we might feel afraid of who we might meet!

I remember one place I stayed in for a solitary retreat that had a “visitors book” and it was moving and inspiring reading the entries. Quite a few of them were from people on retreat, and on their own, for the first time, and they described how those first feelings of anxiety soon gave way to a sense of joy and freedom. We all have our ups and downs on retreat, but we can learn to be OK with that, which is tremendously liberating and confidence giving.

How does it feel when the barrier drops between your inner and outer worlds?

Perhaps we won’t even be aware of it till afterwards. At the time we are not thinking about things like that, we are just absorbed in the world around us. There is a story about the Zen master Dogen that I love. He was asked what it was like to be Enlightened and he said, “it is to be intimate with all things.” In nature I sometimes get glimpses, or intimations, of that. There is a sense of closeness and connection, of love. Trees, stone walls, old winding lanes become like friends! Things become more beautiful and interesting for their own sake.

Years ago I heard a story of a man camping on Dartmoor, probably the wildest part of England. He really tuned into the place. So much so, that if he kicked a stone when he was walking along, he stopped and put it back where it came from. That might sound crazy, but I can understand how he felt. I too can feel that strong sense of care, closeness, and respect, wanting to leave things exactly as I found them, wanting to “live lightly in this world.”

How can a solitary retreat lead you to a realization of your life’s purpose or change you and your perspective?

A friend of mine who was a poet once said that in order to write we need space, and space around the space. In other words, for deeper emotions and thoughts to emerge, the heart and the mind really need lots of time and space. Our lives can often be so full and busy that those deeper parts of ourselves get crowded out and damped-down. We lose touch with what is really meaningful and significant. Of course, the day-to-day stuff we are engaged in may be an expression of what is really important to us, but retreats (solitary or otherwise) are really important for staying in touch with those depths and allowing new inspiration to arise.

How did the places you retreated to become part of your transformation?

In the book I describe some of the beautiful places I have done solitary retreats, and how the landscape and character of a place could have an effect on me. For example, I talk about staying in a lovely old stone cottage on the mouth of an estuary. It was a mile from the road, so you had to bring everything you needed in by foot. When the tide was up, you looked out over a mile-wide stretch of water, like a big lake. When the tide was out, there was an open expanse of sand, with the sea just visible on the horizon. Then the tide gradually snaked its way back again. Birds, fishes, and other sea life moved with the tides. Everything was always moving and changing. I loved the changingness of it – it totally absorbed me. It was an easy place just to be, to be still and content. I think I touched into a deeper contentment than I had ever experienced before. That was partly because of the place, the character and atmosphere of the place. It was generous, abundant, it gave so much to me. The outer world spoke to my inner world, it changed me.

How did your solitary retreats make you feel “closer to life?”

In lots of ways. For example, on retreat you can just feel more alive and energetic. Because there is less external input and stimulation, you can be more in touch with your emotions, and the dreams and reflections of your inner world. You also start to notice the senses more, and what is around you in the external world. Things can feel more raw, but also more real.

One thing I reflect on in the book is encounters with wild creatures – foxes, birds, deer – that have sometimes happened on solitary retreats. For example, I talk about meeting a fox on a mountainside and us just looking at each other for a long time. Like many people, I can find these encounters special, magical, almost like a “blessing.” I have often wondered why we find these meetings with wild animals so significant and wonderful. Again, I think it is about that sense of connection, of overcoming our human separateness from the world. We are drawn out of ourselves and into the world. At the very same time, having that creature gaze at us, in the unblinking way wild creatures just gaze, also throws us back on ourselves. We are aware of them as a creature, with their awareness, looking at us, and that makes us more aware of standing there, being there, as a human being, with our mental faculties and our particular mode of awareness. That is another kind of “closeness to life.”

How can being alone strengthen your connection with others?

This may seem paradoxical, but my experience of solitude is that it helps me be more connected to others. I go back home from a solitary retreat with a stronger sense of those I am close to, perhaps more appreciation of someone, perhaps more understanding. Again, it is about having enough space for the heart to fully open, and for awareness to broaden, so we can really take others in.

Often, when we are too busy for too long, our awareness narrows and our heart closes down. In Wild Awake, one chapter is about a solitary retreat I did quite soon after my father died. This might seem a strange time to choose to be alone, but I found it very helpful. It was a rich and special time. I brought lots of photos of my father from different times in his life and pinned them up on the walls. I had the time and space to really assimilate what had happened, to think of my father, to write down in my journal some of the things he had said in his last months. He was strongly present with me on that retreat: every time I meditated he appeared in my mind’s eye, many nights I dreamt about him. I felt very fortunate to have the time to process his death in this way. Of course there was pain, sadness, and grief, but there was also joy, gratitude, and appreciation.

I understand you are currently writing your next book, Free Time. What did you learn on your retreats that spurred your interest in the subject of time?

I noticed that my experience of time was totally different on retreat. In everyday life I could often be trying to do things fast, so I had more time later. Or trying to get everything ticked off on my “to do” list. Or always planning how I could fit more useful activities into the day, to get more done, more efficiently. But, as Jon Kabatt-Zinn says, “if you fill all your time, you won’t have any.” Time rushes by and feels thin and insubstantial.

On retreat, by contrast, life can seem almost “timeless” in a liberating way. After a few days on retreat, I often feel I have been there for a few weeks. Time feels rich, full, brimming. I am able to have more awareness on a retreat and this means my attention moves along with things as they unfold. I can move along with the day, more in its time and rhythm. Often our attention is leaning back into the past, or straining forward into the future, and this distorts our subjective experience of time. But on retreat we can stay more in the present, which means time feels more relaxed and open. To be more mindful is also to be more time-full!

Wild Awake: Alone, Offline & Aware in Nature is available on Amazon in both Kindle and paperback. Also check out the publisher’s website for more information and a video interview with Vajragupta.

Namaste!

Becca Chopra, author of The Chakra Diaries, Chakra Secrets, Balance Your Chakras-Balance Your Life, and The Chakra Energy Diet