The question of this book’s title grabbed me; as someone congenitally impervious to religion, to understand its appeal and etiology has been a lifelong quest.

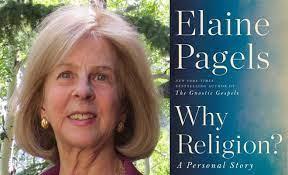

Pagels is a Princeton academic; author of The Gnostic Gospels, in 1998, a controversial book about gospels that didn’t make it into the New Testament, being somewhat out of sync. Why Religion? discusses that stuff; along with the philosophical and cultural ramifications of the Adam and Eve story, the Book of Job, the Book of Revelation, the crucifixion, etc. Pagels herself had an early escape from evangelical Christianity.

She and her husband had tried for seven years to procreate. Medical interventions didn’t help. Then a friend suggests a ritual, saying she’d tried it once before, successfully.

So Pagels attends this woo-woo ceremony, with candles and all. Three weeks later she’s pregnant. Okayyy.

Her son, Mark, is born with a hole in his heart. Fixable by surgery. They had to first wait through an anxiety-ridden year, but it goes fine.

Later they planned a Colorado vacation. Doctors cited a “slight chance” high altitude could give Mark pulmonary hypertension, invariably fatal. How slight, asks her husband Heinz, a physicist. “About one in ten thousand.”

He opines that getting hit by a truck is likelier. But Elaine rejects such science-minded rationalism, refusing to countenance any danger to Mark. So they change vacation plans.

Then comes page 75 and it’s suddenly a different book.

After a routine medical visit for Mark, now 3-1/2, they’re told he has pulmonary hypertension.

There’s no treatment, no cure. And not a long ordeal. By page 87, Mark is dead.

The chapter ends with Pagels asserting she “can tell only the husk of the story.” And that when someone asked how it felt, she’d answered, “Like being burned alive.”

Good thing they didn’t go to Colorado. A child’s death can wreck a marriage; blaming themselves would have assured that. Elaine and Heinz survive. And meantime had adopted an infant daughter; later, another son.

Pagels remarks upon something that’s vexed me too about post-death gatherings: people don’t really talk about the death. She explains this as making suffering sufferable. Of course, religion plays a big role there too. Yet, surprisingly, in this book titled Why Religion?, the pages immediately following Mark’s death almost read as though religion doesn’t exist.

She later relates being “speechless with anger” when someone assured her that Mark’s death would teach her some “spiritual lesson.” Pagels also says, “Whatever most people mean by faith was never more remote than during times of mourning, when professions of faith in God sounded only like unintelligible noise, heard from the bottom of the sea.”

A year after Mark’s death, Heinz is hiking; a cliff’s edge gives way; he’s killed.

A priest officiating at the funeral infuriates Elaine by violating her injunction against preaching. He counsels, don’t be angry with God. “Condescending nonsense,” she calls that.

The next chapter is titled “Life After Death.” But again it’s virtually religionless. Instead Pagels chronicles the emotional storm she went through. I read this in my comfortable lounge chair, out on my deck, in glorious sunshine, my wonderful wife inside, my wonderful daughter across the sea. Mindful of this being life before death.

Eventually, Pagels does introduce religious notions of guilt in connection with death: Adam and Eve brought death into the world by disobeying God, making guilt feelings pervasive — a cultural infusion Pagels cannot shuck, even while recognizing its irrationality.

Another key theme is anger at death. The Bible is full of anger, but it’s overwhelmingly God’s wrath, not human anger. Pagels struggles to make logical sense of some such Biblical tales, while grappling with her own cosmic anger at the two deaths she experienced.

Religionists posit the world as created all good by, of course, a beneficent God, then struggle to rationalize how suffering and evil came into it. (Pagels casts the invention of Satan as a partial solution.) “As if,” she writes, “suffering and death were not intrinsic elements of nature but alien intruders on an originally perfect creation.”

While Pagels does place her scholarly examination of religious concepts in the context of her own grappling with unfathomable losses, never did she succumb to seeking solace in that quarter. Her final line: “However it happens, sometimes hearts do heal [her emphasis], through what I can only call grace.”

Recently reading a short history of philosophy, I saw how trying to rationalize ideas of god plunged thinker after thinker off the rails into nonsense. Always seeking some sort of “unity.” Yet Augustine divided “the City of Man” from the “City of God.” A route to confoundment. But there is indeed unity — only one reality. If we can just accept this simple truth, putting aside god nonsense, we can get on with living in it.

(Footnote: The final chapter contains an unfortunate detour, venting against the Iraq war. Saying we invaded Iraq only when pursuing Afghan targets “proved too difficult” (I seem to recall a preceding Afghan war); saying Bush declared a “‘crusade’ against Muslims” (which he explicitly disavowed); and rehashing the myth that protests “were banned from television news — suppressed.” (I actually recall wearying of such coverage.) Pagels even gets the century wrong — not the Twentieth!)