For the uninitiated, SKAM (or Shame in English) is a Norwegian TV show, aimed at teenagers, that detail the lives, loves and confusions of the students of a particular posh high school in an Oslo suburb, focusing on one character’s story per season. It’s all in Norwegian, and rough translations are done by amateurs and only available to watch on Tumblr or via download links that disappear almost as soon as they’re made live. And yet, SKAM is building a loyal, hungry audience – and it’s not just teenagers who are gripped.

The show is now in its third season and focusing on 17-year-old Isak, who’s on the cusp of coming out thanks to a sexual awakening by new arrival at his school Even, and when I first wrote about it for Gay Times, it was easy to see why some may have thought my interest in it was more down to my being a dirty old man than genuinely interested in the storytelling. It’s an old homophobic trope, that we’re only too happy to encourage, that any older gay man interested in what a teenager has to say has sexual motives, or is a paedophile.

The season 3 trailer featured a highly stylised dreamlike sequence – from Isak’s imagination, I guess – as our hero gazes upon his classmates in the locker room, in wonder, horror and embarrassment, on the outside looking in, when a carton of milk splatters on the locker above him, drenching him in it. It doesn’t take the Enigma machine to work out the symbolism the producers were going for, but the show is known for its glossy, suggestive trailers – the previous series trailer saw the main character, Noora, wake up in a room full of semi-nude beauties and a huge dildo on the floor – and it’s not at all representative of the series as a whole.

“You’re only interested in the men,” said one Facebook commenter. “Sexualising teenagers is OFF,” cried another. But the fact is teenagers are having sex, whether we care to admit it or not, and they certainly sexualise each other. We were all teenagers once and, depending on our confidence and social standing, having sex too. Why should’t we be interested in a show that tells stories like this so sensitively, and so well?

I’m not the only one who finds this window into a world a generation or two below us fascinating. Even SKAM’s Tumblr fandom –traditionally behind the velvet rope for most people over 25, includes avid viewers well into their 30s and their 40s. Since writing about the third series I’ve been contacted by people of all ages to say how much they love it and do I know where they can see more.

So why is SKAM hitting home with people in their 20s, 30s and 40s? Is it really just a prurient interest in what teenagers do beyond Snapchat and Insta, or is it because, essentially, teenage problems are timeless – it’s only the tec that has changed? In the case of Isak’s story, it may be decades since some of us came out, and our own situation would have been wildly different from that of a privileged, yet messed up, Norwegian teenager, but the fact coming out still exists at all means we can still feel an affinity – and a pretty large one at that.

Coming out isn’t usually portrayed that brilliantly on screen. Oh, sure, we tell ourselves it is, but usually we’re just so grateful to see a gay couple kiss or sit up in bed together that we’ll take pretty much any interpretation of our story. Usually, there’s either generous lashings of angst and misery, or Hollywood impossibility presented as fact, but it’s rare for a drama to get the balance just right – the perfect mix of wish-fulfilment, hope (both raised and dashed), lust, longing and, more importantly, everyday life. Because, even if your sexuality is tearing you to shreds on an hourly basis, life goes on, and you have no choice but to live it.

Isak and Even’s story begins with glances across a cafeteria but is given a kick start as they both escape a boring extracurricular group and go for a smoke. Quickly, Isak is hooked, doing all the stalker routines we never admit to anyone that we ourselves do – Googling Even, scrolling through his Insta, watching his videos and finding out what he’s into. Soon, Isak is immersing himself in all things Even, watching his favorite movies, listening to his preferred music and even having cardamom on a cheese toastie (long story).

Dramas come in the form of girlfriends, fear of homophobia and insecurity, which all block the path of true love. The use of girlfriends in the story is particularly painful to watch at times: many gay men have been guilty of using teenage girlfriends as smokescreens, playing with their emotions – very seldom in malice, but playing all the same – to hold on to their social standing or escape bullying. It’s a stark reminder that homophobia is harmful to everyone, LGBT or not.

The long silences and stultifying scenes of pretty much nothing are the most realistic of all. That’s the thing with coming-out stories, they can’t be quickly packaged up into convenient episodes. They don’t lurch from one dramatic scene to another, with killer lines delivered, before sweeping out of a room victoriously. They lumber along, slowly. They’re the dimmest of lights from the last embers of the fire, barely visible, but still not giving up hope that somehow, from somewhere, some kindling will turn up and make them burn brighter than before. But while we wait for the spark, we remain on a low light. We go to school, we queue for our lunch, we listen to the teacher and we do our homework. We still get the bus, we watch our favorite TV shows – and we still enjoy them – and we get the sleepless nights, but not every night. Life goes on, and while we may pine and worry, for the most part it’s buried deep within. It’s not so much a secret, or something shameful, just the thing that you can never acknowledge is happening, or tell the world, because once you do there is never any going back, and while the thought of it both excites and terrifies you, you cannot imagine life beyond it. You think it came never be. But all you know it is everything you long for and everything you’re scared of. It is in turns the entire world to you and utterly meaningless.

This is why SKAM works so well. It’s both the coming-out we recognize and the one we wished we had. All the things Isak is dying to say, we wanted to say too, and when he says them and gets them all wrong and moves his progress at least ten steps backward, we nod and say, “Yes, that’s how it would have gone for me if I’d dared to say it” and when he wins, and has Even with him again – whatever we may think of the suitability of that relationship – we wonder if that could’ve happened to us. And perhaps then we kick ourselves for wasting so much time, or not taking a chance. Every lurch in Isak’s stomach is our own. We root for him, and he both delivers and disappoints. Maybe we can’t exactly identify with him now, but we can relate. We are all Isak at some point in our lives, but Isak can’t be all of us.

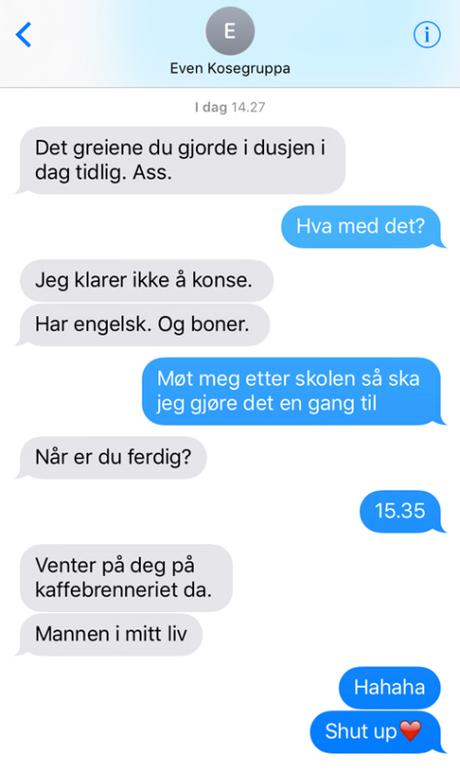

It’s an immersive, almost claustrophobic experience, with clips added to the SKAM website in real time, and screenshots of text messages between Isak and the other characters. We’re living every moment with him.

Of course, the story has to move forward, so suspension of disbelief is required at certain stages. The flirtation kind of comes too quickly – although the bonding over music and dope is certainly how a lot of these things start, turning from hero worship into attraction before you’ve even realised it. And of course the sad truth with these things is that they are very often a one-way thing. It’s almost unthinkable that Isak would somehow manage to fall for another ostensibly straight guy that fancied him back, although Isak did harbor a crush on his best friend Jonas for long enough, which was unrequited. A limited timeline – the show happens in real time, so the entire story has to be played out within the confines of the ten-week run – means that silences that could last months have to be broken, but Isak’s sexuality hasn’t come into question overnight. The previous two seasons have touched upon it, from his interesting browsing history to his sham girlfriends; the evolution of this storyline has been totally on the level.

While Isak isn’t exactly a hugely popular student, some LGBT viewers whose adolescence was more of a struggle could be forgiven for feeling mildly envious of his situation. In one scene, shortly after he comes out to his close gang of buddies, they coach him on how to play it cool over text with Even. Why couldn’t I have had a a group of lads like that, you may wonder. How different might things have been if had? You’re thrilled for Isak because even thought it’s painful for him, he has that support network, he gets to go to the big parties, and you know, above all, he has time and progress on his side so it’s likely he’s going to be all OK. And even though Isak is a fictional character, your envy turns to hope.

But just as every coming-out is different, so must Isak’s. Years of unrequited crushes, furtive masturbation and trying to pass as straight is a pretty thankless way to spend your youth, and while we may wish our journey could’ve been as romantic and charged with passion as Isak’s, we know deep-down we couldn’t have that kind of coming-out for ourselves, and nor should we have. How we came out and dealt with our sexuality in our younger days made us who we are now. For better or worse, there was only one road to take. The main hope is that Isak’s story will inspire someone yet to embark upon their journey, and, when they do, keep them on course.

Fasten your seatbelt, kid, it’s going to be a bumpy forever.

Images: NRK/YouTube