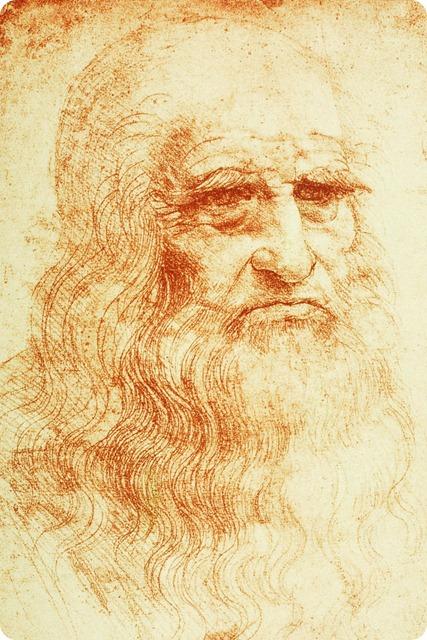

Leonardo da Vinci is the Shakespeare of art and engineering. Both creative titans died many centuries ago, but live so vibrantly in modern imaginations they feel like our contemporaries.

Getting into the hottest new Shakespeare production is a tricky business but this weekend, I finally watched Michael Fassbender in Macbeth. The text was too severely cropped,

I thought, but it's a marvel that in our century, which thinks itself so new, Shakespeare's dramas are still so damned hot. It's the same with Leonardo - witness the National Gallery queues for his blockbuster show in 2011.

Combining Da Vinci's flying machines and designs for death and destruction, this model show eerily connects humanity's love of beauty and its thirst for war

Not one but two fascinating Leonardo exhibitions open in the UK this week. At the Science Museum in London, a spectacular survey of his inventions will reconstruct some of the flying machines, armoured cars, alarm clocks and hydraulic systems whose intricate, gorgeously drawn designs fill his notebooks. Meanwhile, at the Laing gallery in Newcastle, you can see some of his most powerful drawings, each one a masterpiece illuminating one of humanity's finest minds.

So what have Leonardo and Shakespeare got that other Renaissance artists and writers have not? Why don't we get similarly excited about Raphael or Edmund Spenser? The answer is that they are artists of the people. Neither went to university; both were in many ways self-taught, their capacious minds not limited by the elitist culture of Renaissance humanism. They embraced popular culture, popular ways of thought, and that speaks to our democratic age.

The Renaissance was an intellectual revolution kickstarted by scholars rediscovering the classic texts of ancient Greece and Rome. The wisdom of these pagan authors gave a licence to explore the human condition in a new and richer way. Leonardo had only partial access to that high culture. His main education was as an apprentice painter in 15th-century Florence. You needed to know enough stories from mythology to put them in your paintings, but there was no need to understand Latin or Greek. Yet, Leonardo taught himself everything he could find out around him - including Latin, but also so much more.

He watched builders and studied the mechanics of their cranes; talked to soldiers about the latest weapon designs; observed the way birds fly. This programme of self-guided learning started when he was young and continued all his life. Leonardo's greatest artistic achievements are not his handful of surviving paintings, but the drawings and notes in which he explores the world. The notebooks showing the originals designs for the model machines on display at the Science Museum may seem like secret books of wisdom. They are not. They are something much more beautiful: the record of a lifelong quest for understanding.

Shakespeare, like Leonardo, sought out most of his knowledge by himself, from books he read; from conversations with peers such as Christopher Marlowe (who probably told him about Leonardo's old mate Machiavelli); and above all from observing the world around him. He listened to the speech of the streets.

Shakespeare's imagination is as democratic as Leonardo's. And Leonardo, for his part, is as universal a character as Shakespeare's Hamlet, whose uneasy and restless mind could almost be a portrait of his endlessly questioning genius: "What a piece of work is a man."

Other cultural greats can seem remote but Leonardo and Shakespeare soar into the digital future on a wooden flying machine that won't ever stop.

If you liked this article, subscribe to the feed by clicking the image below to keep informed about new contents of the blog:

I hope you enjoyed this book. If you have any questions, or want to supplement this post, please write in the comments area. You can also visit Facebook, Twitter, Google +, LinkedIn, Instagram, Pinterest and Feedly where you'll find further information in this blog. SHARE THIS!