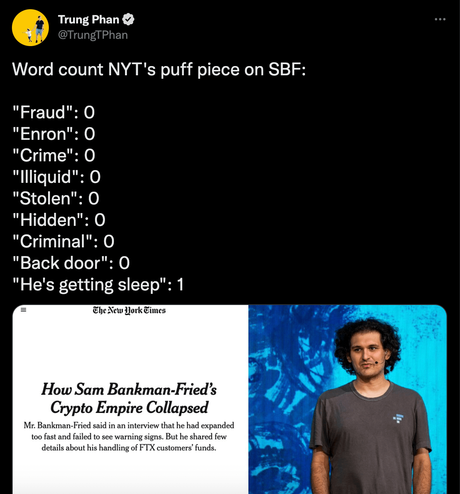

Crypto Twitter has been spinning up conspiracy theories on why the New York Times article on FTX collapse never mentioned some of the confirmed facts:

The so-called “Sam coins”, illiquid altcoins that inflated the balance sheets of FTX, the extravagant handling of customer funds, the heavy stimulant use among other things reported by insiders through the Twitter account @AutismCapital.

Mainstream media paint the FTX collapse as an unfortunate liquidity crunch on a business that may have been faking it till they make it, but essentially did nothing criminal.

The business model was sound, it just got caught up in a series of unfortunate events.

The history repeats itself

Banks were not always available to just anybody. For a long time they were reserved for the aristocracy and after the industrial revolution, to wealthy business owners. This started changing in Germany in the second half of 19th century.

The concept was called “Volksbank” which I will translate as community bank in this article, but they were commonly known under the name they took after the author of that concept: “Raiffeisenbank”.

Initially, the business model of community banks was to take customer deposits and loan or reinvest them for yield. They would charge higher interest yields on their lending because their customers were underserved; working people in those days could not easily get credit. These higher yields then made for higher interest rates on deposits which attracted new customers.

The concept was copied across the former Austria-Hungary which is how it spilled over into Eastern Europe.

But while in the West the community bank concept grew and evolved during the 20th century, in the East it eventually culminated in a 1990s series of bank runs very similar to the FTX collapse.

Those bank runs have caused a large number of community banks in the East to crash. That usually happened when there were doubts about the bank’s solvency voiced somewhere publicly. Depositors typically did not want to risk anything hearing of the rumors and started withdrawing. Some got out while others never did and that was fair because the community bank was allowed to run on a fractional reserve.

In these situations the chief officers of the community bank would usually lie whenever they got the chance, knowing that further bank runs would only make things worse as there would be less liquidity to reinvest to hopefully make depositors whole.

Eventually, it was found that there was usually a lot of liquidity lost in an investment that was not risk-checked, in an investment into an entity that was too closely dependent on the community bank’s financial standing or in an investment into a business that flopped.

I don’t know, does any of that sound familiar?

So, would regulations solve the issue?

No.

Due to the string of small institute bankruptcies in the 1990s, there was a push to regulate them as it was obviously the individual depositors who ended up losing money. Regulators responded and since early 2000s, European community banks became money businesses that usually do not have a full banking license but they still have the right to get bailed out by the central bank in case of liquidity crunch, along with any regular bank.

On paper, the following will look great to a lot of those who got rugged by FTX, Bitfinex or Gox:

Under the regulation, a liquidity-strained community bank may deliver a “notice of insolvency” to its central bank. The central bank runs a dedicated insurance fund that all its money businesses contribute to. Using that fund, the central bank pays off all customer deposits within 30 days of the notice of insolvency, up to value of 100 000 EUR per depositor.

Why does this not solve anything?

As soon as deposit insurance was introduced for community institutes in Europe, a lot of people saw what the game was: As a depositor with 100% deposit insurance, you go after the highest yield available regardless of the degeneracy that makes said yield possible.

Unsurprisingly, what this led to was a strong political lobby from the larger banks against the whole community bank sector. In 2014, the official in charge of the central bank insurance fund of a small European country explained:

“We saw that people did not learn from the collapse of [a popular community bank] and did not move their deposits to a larger institution. Instead they kept switching from one community bank to another. It will not be surprising that the vast majority of these deposits were up to 100 000 EUR, the deposits were thus fully insured. The regulatory protection of customer funds created a moral dilemma now as the large banks - who are more conservative with their earning strategies but have larger volumes - contribute a much larger amount of money to the deposit insurance fund system, while the fund primarily helps the community banks. The community banks even use the fund as a marketing tool to attract new clients, so in the end the big banks are essentially financing their competition. It is not surprising that there is a lot of pressure from their side to limit the community sector.”

Why did some community banks survive?

When Europe split into East and West after the Word War II., the concept of community banks took two very different routes in each of those parts.

Community banks were initially competitive because they offered better yields than the larger banks, but in East vs West they took two different routes to make those yields possible.

In the East, for the most part the business of community banks stayed firmly within the numbers game: Community banks would receive client deposits and either lend them out or otherwise invest them for a relatively high yield.

As the banking sector grew, community banks chose to stay competitive by seeking riskier investments or lending for a higher interest rate in exchange for a more generous or sometimes no credit scoring system.

This made them susceptible to bank runs as inevitably some part of the customer deposits was locked up in illiquid investment schemes or lost in loans to bankrupt subjects.

In the West, the economic situation started improving with the end of the World War II. That created a lot of avenues to diversify the income streams of the community institutes. The lexicon of Bavarian history writes:

“With the economic growth after 1948, individuals started increasingly demanding other services such as consulting, financial advice, investment services, business travel funding or housing construction financing. The German ‘banks for everyone’ developed into universal banks with a complete range of financial services.”

Some of these services created income streams that did not derive from customer deposits for the original Raiffeisenbanks. And because the community banks were still established locally and had a long experience working with a specific underserved client base - the working professional, instead of the landed person who looked for management of inherited wealth - they had an advantage over the larger banks.

The equivalent of this route in crypto could probably be crypto custody services such as what Coinbase offers, blockchain analysis for fraud detection or credit scoring, merchant payment services and any kind of crypto-specific investment advice.

I would venture a guess that the (alleged, I suppose) business model of Alameda which was to front-run certain trades was a poor attempt at this kind of diversification.

Assuming no wrongdoing or conspiracies, an exchange like FTX would need these additional sources of income to afford operations with the extremely low trading fees that they charged. This is all just a speculation but I think it is unlikely that the business was set up in a very different way.

In the second half of 20th century, most of the independent community banks in Europe eventually merged and were consolidated into a centralized hierarchy of institutions. But the tools they originally developed to stay competitive did not disappear.

To this day, some of the former community institutes still offer the easiest way for a retail trader to gain trading access to the stock exchange or for a resident of the EU to open a USD-denominated bank account. In European countries with a history of community banks these issues were resolved decades prior to Robin Hood and Revolut.

Bottom line

It does not matter whether SBF wins back his lost 8bn and makes FTX rise from the ashes, ultimately a system based mainly on financial speculation will never not be vulnerable to what happened to FTX.

Maybe it will take the collapse of Binance for the industry to move on.

Maybe the industry will never move on and a long string of collapses will pave the way to central bank issued digital products, who knows.