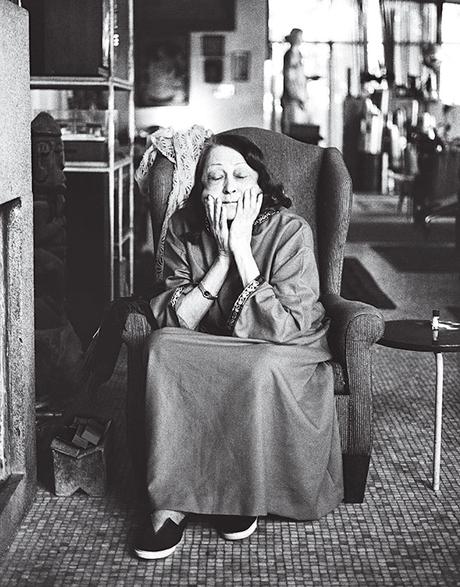

A 1990 portrait of architect Lina Bo Bardi in her São Paulo home, which she designed and completedin 1952.

Photo by Juan Esteves.Author, architect, and professor Zeuler Lima has dedicated the better part of his career to studying the work of 20th-century architect Lina Bo Bardi. Born Achillina Bo, in Rome, Italy, Bo Bardi relocated to Brazil in 1946 and set up practice there, creating some of the best-known buildings in the country, including the São Paulo Museum of Art. In his book, Lina Bo Bardi (Yale University Press) and in the companion film, Lina Bo Bardi, Curator, a special commission by Munich’s Architekturmuseum on the occasion of Bo Bardi’s birth centennial in 2014, Lima invites the audience to experience the intricacies of the elusive Italian expatriate’s work.

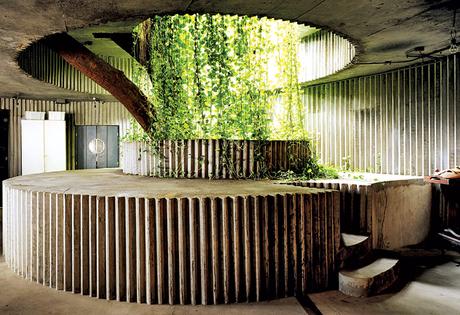

Part of the Misericórdia Hill housing complex in Salvador, Bahia, the Coaty Restaurant designed by Bo Bardi in 1988 uses lightweight, prefabricated ferro-cement panels developed by Brazilian architect João Filgueiras Lima.

Photo by Nelson Kon.When did you start this project, and how did you tackle such an undertaking?

A book of such complexity took more than a decade to complete. I started the project as a postdoc fellow at Columbia University in 2001 and continued with comprehensive archival research and interviews in Brazil and Italy until completing the original manuscript in 2012. Interest in Bo Bardi is growing, but I hear a lot of inaccurate interpretations around—I hope the book will encourage deeper knowledge.

How important is Bo Bardi’s influence on Brazilian modernism? Was she accepted as an expat in Brazil?

She is undeniably among the most important architects of the 20th century, and not just in Brazil. Her multifaceted career finally blossomed when modern architecture was in crisis in the 1970s.

She had an ambivalent relationship with the Brazilian establishment, especially in the 1950s. She was a strong-minded woman in a macho culture, and a foreigner married to a controversial museum director [Pietro Maria Bardi]. With greater maturity and independence, she embraced the Brazilian counterculture along with young artists in the 1960s. Opinions about her work were never unanimous, but it was finally recognized at the end of her life.

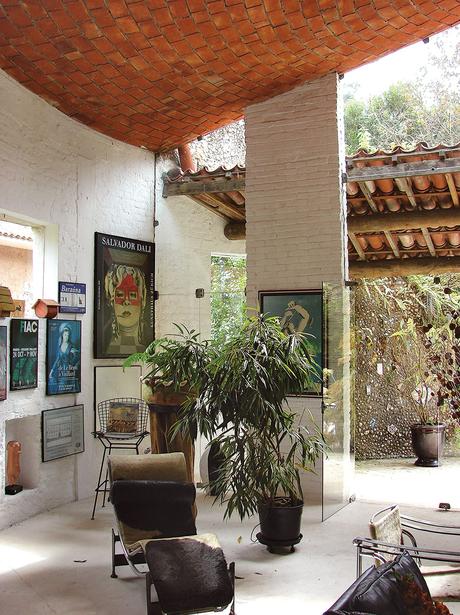

The living room of La Torraccia, a small guesthouse addition Bo Bardi designed in 1964 for the Cirell House in São Paulo, at once recalls vernacular architecture and the curvilinear forms of Spanish-Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí.

Photo by Zeuler R. Lima.How did Bo Bardi’s process compare with that of her contemporaries?

Her drawings and hand-painted studies may be understood as storyboards for architectural scenarios. Unlike many conventional and well-known designers, Bo Bardi felt that architecture should not just be a formal and visual object, but a place for the staging of life. Her drawings, even from her youth, conveyed that worldview.

How did her early work in Milan inform her work in Brazil?

Aside from Bo Bardi’s formative exposure to meaningful artistic sensitivities among Milanese architects and designers in the early 1940s, it was the experiences of World War II and of reconstruction that opened her eyes. In Milan, she started to understand and explore the political and social dimensions of architecture.

What’s the most surprising thing you discovered about her in your research?

I was especially moved by her resolve and her will to live in face of hardships she encountered along her existence; her personal and professional challenges were intertwined from the start. She was an ambitious young woman coming of age during Fascism and World War II. She arrived at her maturity aware of the predicaments—and also the advantages—of being a woman and an outsider in a conservative, masculine profession in both Italy and Brazil. More than surprises, what really interested me was the deep understanding of her complex—and sometimes contradictory—life and work.

- Log in or register to post comments