In a previous post I quoted Langston Hughes' 1938 poem "The Kids Who Die", which is very powerful in the context of our current crisis of police use of deadly force against black men. "Kids will die in the swamps of Mississippi / Organizing sharecroppers / Kids will die in the streets of Chicago / Organizing workers / Kids will die in the orange groves of California / Telling others to get together / Whites and Filipinos, / Negroes and Mexicans, / All kinds of kids will die / Who don't believe in lies, and bribes, and contentment / And a lousy peace." In the third stanza Hughes writes "To believe an Angelo Herndon, or even get together". Who was Angelo Herndon?

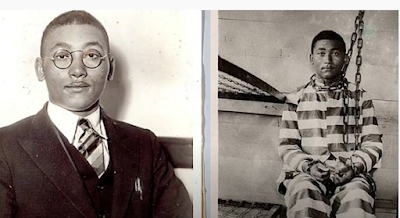

Herndon was a self-educated advocate and organizer for workers' rights and racial equality in the 1930s. He describes his early life of labor and social activism in Let Me Live, published in 1937 when he was only twenty-four years old. His life and arrest and conviction in Georgia for insurrection are described in Charles Martin's The Angelo Herndon Case and Southern Justice. As a teenager Herndon worked as a laborer and miner under highly exploitative conditions, and eventually became an organizer for workers' rights and racial equality. Introduced to the Communist Party in the early 1930s, he found the party to be the first organization he had encountered that was not racist, and he joined the party and became an organizer for the Unemployment Council in Atlanta. In 1932 he was arrested by Atlanta police and accused of insurrection, and was convicted on the basis of his possession of Communist literature. He was defended by the International Legal Defense, affiliated with the Communist Party. His case went to the Supreme Court, which declined to hear the case twice in 1935. Finally in 1937 the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case and found that Georgia's anti-insurrection law was unconstitutional. Law professor Kendall Thomas refers to the Supreme Court decision of Herndon v. Lowry as "generally acknowledged as one of the great civil liberties decisions of the 1930s" (link).

Herndon was a radical and articulate advocate for workers' rights for both white and black workers, and he was very willing to challenge Jim Crow racism when he saw it. Kendall Thomas refers to Let Me Live as an example of "the popular tradition of Afro-American resistance literature", and an instance of "insurgent political consciousness among African-Americans at one key moment in our national past" (2610). As a young man writing Let Me Live, Herndon was scathing in his descriptions of African-American leaders for racial justice including W.E.B. Du Bois, on the ground that they were not radical enough in their attacks on white racism. Quoting Thomas again, "The Angelo Herndon case powerfully underscores the extent to which the history of the struggle of Afro-American people against an oppressive cultural (social, political, and economic) order has also always been the history of a struggle against an oppressive discursive or symbolic order."

The most powerful political organization that influenced Herndon in his teens and twenties was the Communist Party USA. It appears that the Communist Party's program, leaders, and strategies were quite different in the American South, and were adapted to addressing the injustices of Jim Crow racism. Robin Kelley's Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression is a detailed history of black Communism in Alabama. It is a truly fascinating book to read. Here is how Kelley describes the Alabama Communist Party in the preface:

Built from scratch by working people without a Euro-American left-wing tradition, the Alabama Communist Party was enveloped by the cultures and ideas of its constituency. Composed largely of poor blacks, most of whom were semiliterate and devoutly religious, the Alabama cadre also drew a small circle of white folks—whose ranks swelled or diminished over time—ranging from ex-Klansmen to former Wobblies, unemployed male industrial workers to iconoclastic youth, restless housewives to renegade liberals.It is genuinely fascinating to see how the ideas of Marx and Engels were considered, debated, and reshaped in the context of racist capitalism in the American south. Herndon's memoir provides numerous examples of his excitement at finding in Marx the language and ideas that he had been seeking to articulate his own construction of the relationship between white owners and black workers. Here is how Herndon paraphrases the Communist Manifesto in his own words (as a man of about twenty):

What emerged was a malleable movement rooted in a variety of different pasts, reflecting a variety of different voices, and incorporating countless contradictory tendencies. The movement's very existence validates literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin's observation that a culture is not static but open, “capable of death and renewal, transcending itself, that is exceeding its own boundaries.”

The experiences of Alabama Communists, however, suggest that racial divisions were far more fluid and Southern working-class consciousness far more complex than most historians have realized. The African-Americans who made up the Alabama radical movement experienced and opposed race and class oppression as a totality. The Party and its various auxiliaries served as vehicles for black working-class opposition on a variety of different levels ranging from antiracist activities to intraracial class conflict. Furthermore, the CP attracted some openly bigoted whites despite its militant antiracist slogans. The Party also drew women whose efforts to overcome gender-defined limitations proved more decisive to their radicalization than did either race or class issues.

The worker has no power. All he possesses is the power of his hands and his brains. It is his ability to produce things. It is only natural, therefore, that he should try and get as much as he can for his labor. To make his demands more effective he is obliged to band together with other workers into powerful labor organizations, for there is strength in numbers. The capitalists, on the other hand, own all the factories, the mines and the government. Their only interest is to make as much profit as they can. They are not concerned with the well-being of those who work for them. We see, therefore, that the interests of the capitalists and the workers are not the same. In fact, they are opposed to each other. What happens? A desperate fight takes place between the two. This is known as the class struggle. (Let Me Live, 82)Following his release in 1937 Herndon continued to combine activism with literature where he gained some prominence, and he co-edited a short-lived journal, Negro Quarterly: A Review of Negro Life and Culture, with Ralph Ellison for a short time. Herndon left the Communist Party in the late 1940s and died in 1997. (This entry in the New Georgia Encyclopedia provides a few biographical details; link.)

Looking into the life of Angelo Herndon -- stimulated by reading the poetry of Langston Hughes -- I am struck once again by the fundamental multiplicity and plurality of history. It is sometimes tempting to tell a unified narrative of a large historical process -- the rise of liberalism, the struggle of African-Americans for freedom and equality, or the development of radical populism -- as if there were a single main current that characterizes the process. But in reality, almost any historical epoch is a swirling process of tension, conflict, and competing groups, and many stories must be told. This is certainly true in the case of African-American history, where radically different visions of the future and conceptions of needed strategies were at work at any given time. The distance between an Angelo Herndon and a W.E.B. Du Bois is as great as that between Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Eldridge Cleaver or Stokely Carmichael. And yet all of their stories are part of the long history of struggle for emancipation, equality, and dignity that America has lived. That is perhaps part of the meaning of Langston Hughes' refrain: "(America never was America to me.)"