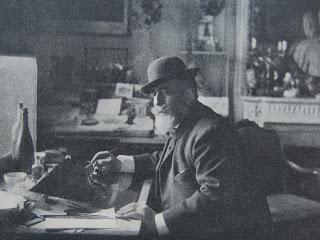

Photograph by Manuel of Jean-François Raffaelli in his studio,

Photograph by Manuel of Jean-François Raffaelli in his studio,a drypoint needle in his hand, and a copperplate before him.

Wearing a bowler hat.

Jean-François Raffaëlli was one of the most innovative printmakers of the late nineteenth/early twentieth centuries. He is especially celebrated for his mastery of color etching, which he championed at a time when conventional snobbery insisted that color prints were vulgar and not worthy to be exhibited alongside the purity of black-and-white.

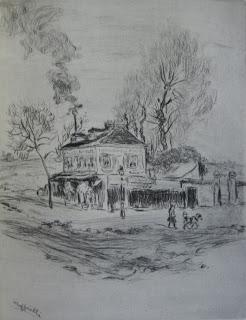

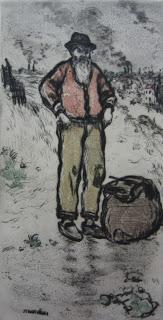

Jean-François Raffaëlli, Le terrain perduDrypoint, 1894Delteil 16 ii/iiBlack plate only, with plate tone; the first state was in colour

Jean-François Raffaëlli, Le terrain perduDrypoint, 1894Delteil 16 ii/iiBlack plate only, with plate tone; the first state was in colourBorn in Paris in 1850 to an Italian father and French mother, Raffaëlli was essentially a self-taught artist, though he did spend some time studying under Gérôme at the Beaux-Arts, Paris. Raffaëlli soon rejected history painting and found his own subject matter in the poor of Paris. He was hailed as the artistic equivalent of Zola, and the city counterpart of Millet.

Jean-François Raffaëlli, Le rémouleurDrypoint, 1907Delteil 76 iii/iiiThird state in black only, after the plate had been cut down

Jean-François Raffaëlli, Le rémouleurDrypoint, 1907Delteil 76 iii/iiiThird state in black only, after the plate had been cut down Jean-François Raffaëlli, La neige (soleil couchant)Drypoint, 1907Delteil 77 v/vRight portion, after the plate was cut in two, in black onlyThis and the following image were once part of the same composition (which can be seen here)

Jean-François Raffaëlli, La neige (soleil couchant)Drypoint, 1907Delteil 77 v/vRight portion, after the plate was cut in two, in black onlyThis and the following image were once part of the same composition (which can be seen here) Jean-François Raffaëlli, La neige (soleil couchant)Drypoint, 1907Delteil 77 v/vLeft portion, after the plate was cut in two, in black only

Jean-François Raffaëlli, La neige (soleil couchant)Drypoint, 1907Delteil 77 v/vLeft portion, after the plate was cut in two, in black onlyAlthough in the 1870s Jean François Raffaëlli was working in an essentially realist mode, his art was greatly admired by Degas, with whom he mixed at the Bohemian artists’ café La Nouvelle Athènes (the kind of milieu depicted in the drypoint Les rapins, The artists). It was Degas who invited his friend to exhibit at the 5th Impressionist exhibition of 1880. Raffaëlli seized the opportunity to exhibit with the avant-garde, and showed 34 paintings, pastels, and drawings. The following year he showed another 33 works. Some of the established Impressionists were less than impressed with this attempt to take over the show, and Caillebotte and Pissarro made sure he was not invited again.

Jean-François Raffaëlli, Sous la pluieDrypoint, 1909Delteil 86 ii/iiA self-portrait of the artist buffeted by the elements

Jean-François Raffaëlli, Sous la pluieDrypoint, 1909Delteil 86 ii/iiA self-portrait of the artist buffeted by the elements Jean-François Raffaëlli, Les rapinsDrypoint, 1909Delteil 87 ii/iiBlack plate only

Jean-François Raffaëlli, Les rapinsDrypoint, 1909Delteil 87 ii/iiBlack plate only Jean-François Raffaëlli, Au coin de la routeDrypoint, 1909Delteil 88Unique state

Jean-François Raffaëlli, Au coin de la routeDrypoint, 1909Delteil 88Unique stateIt was not really until Raffaëlli took up etching around 1890 that he fully embraced the Impressionist aesthetic. The catalog raisonné of his prints by Loÿs Delteil lists 183 prints, of which all but 5 are etchings or (more commonly in later years) drypoints. Interviewed in New York in 1894 for The Art News, Raffaëlli said, “a few years ago I took up etching. I did not know anything about the engraver’s technique. I simply bought a few books on etching, studied them, bought the material, experimented, and eventually I made some etchings as good as anybody else.” One technique that interested Raffaëlli was that of leaving the copper plate only partially wiped, to achieve a background gray known as plate tone; this is particularly effective in a plate such as Le terrain perdu, where the lower half of the plate has plate tone representing the land, and the upper half representing the sky is wiped clean. The fact that this causes problems for the printer is illustrated by my copy of Le terrain perdu, which has a couple of inky fingerprints in the margins!

Raffaëlli started experimenting with color etchings in 1889, around the same time as Henri Guérard and Mary Cassatt; when the Société de la gravure originale en couleurs was founded in 1905, Raffaëlli was its first President.

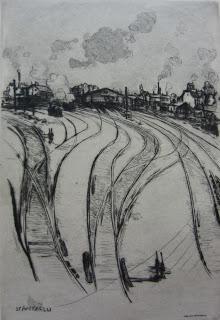

Jean-François Raffaëlli, La gare du Champ-de-MarsDrypoint, 1911Delteil 90 ii/ii

Jean-François Raffaëlli, La gare du Champ-de-MarsDrypoint, 1911Delteil 90 ii/ii Jean-François Raffaëlli, Le chiffonierColour etching, aquatint and drypoint, 1911Delteil 97

Jean-François Raffaëlli, Le chiffonierColour etching, aquatint and drypoint, 1911Delteil 97Jean-François Raffaëlli was the illustrator, with original etchings, of perhaps the most severely limited printed book of all time, an edition of Germinie Lacreteux by the de Goncourt brothers published in an edition of precisely three copies. Raffaëlli was a significant figure in the Paris literary world; Joris-Karl Huysmans partly based the figure of the artist in À vau-l'eau on him.

Jean-François Raffaëlli, Le petit oiseauColour etching, 1915Delteil 104 ii/iiOne of 100 hand-signed copies on Japon paper, the frontispiece for Loÿs Delteil, Le peintre-graveur illustré, tome 16, 1923

Jean-François Raffaëlli, Le petit oiseauColour etching, 1915Delteil 104 ii/iiOne of 100 hand-signed copies on Japon paper, the frontispiece for Loÿs Delteil, Le peintre-graveur illustré, tome 16, 1923Raffaëlli died in Paris in 1824. As a painter he seems to have been almost forgotten, but his compassionate and heartfelt art has kept him at the forefront of Impressionist printmakers. His deep affinity with the poor and dispossessed means that many of his finest works depict rag-pickers, beggars and the like. Renoir noticed with amazement that painting the same Parisian banlieus the two artists saw things with such different eyes. For Renoir, everything was bathed in sunshine and delight, whereas “In his pictures, everything is poor, even the grass!”