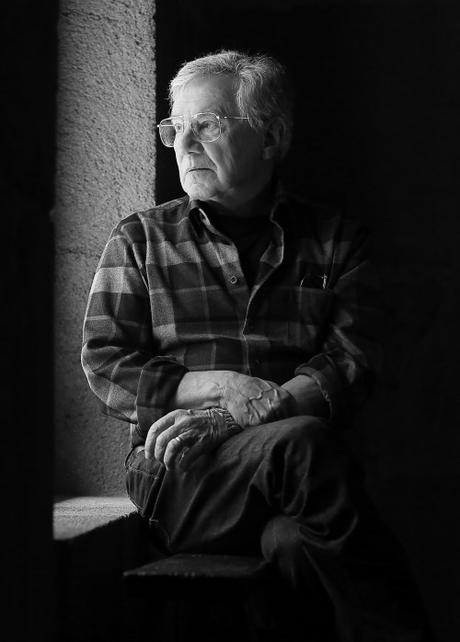

In 1968, Dr. Bernie Krause was leading a booming music career. A prodigiously talented musician, he’d played guitar on Motown records as a teenager, replaced Pete Seeger in the folk band The Weavers in his twenties, and had become a pivotal figure in electronic music by age 30, mastering the synthesizer and introducing it to popular music and film. He worked with artists like The Doors and the Beach Boys, performed music and effects for iconic soundtracks for more than 130 films and shows like Apocalypse Now and Mission Impossible, and co-produced game-changing albums showing the world how the synthesizer could combine sounds into new timbres.

Then Warner Brothers commissioned his duo, Beaver & Krause, to create the first-ever album incorporating the sounds of wild habitats. Bernie headed into Muir Woods north of San Francisco with a portable recorder, mics, and stereo headphones. What he heard changed his life. A flowing stream; gentle winds in the tall redwood canopy; a pair of calling ravens, feathers resonating with each wingbeat. It was an immense new world of music. Listening to it made him feel calm, focused, and simply good in a way he hadn’t felt before.

Bernie decided he wanted to record wild animals for the rest of his life. And that’s what he did. He quit Hollywood, got a PhD studying bioacoustics (back when the field comprised about five people) and began traveling the world to record wild habitats. Over the past fifty years, he’s built what The New Yorker aptly called “an auditory Library of Alexandria for everything non-human.” His astonishing archive includes the sounds of more than 15,000 species, from barnacles twisting in their shells, to chorusing tropical forest frogs, to feeding humpback whales.

Visualizations of sound frequencies, known as “spectrograms,” are useful for understanding acoustic patterns in habitats. In 1995, in Vanua Levu, Fiji, Bernie Krause recorded two sections of the same reef: one alive and one dying. The first 15 seconds of this spectrogram capture what the healthy reef sounded like. Bernie estimates there were about 15 different types of fish. The latter 15 seconds were recorded within the same hour at a dying portion of the same reef, about 400 meters away. The diverse voices of fish are absent. All you can hear is snapping shrimp and the waves. (Courtesy of Bernie Krause)Previous wildlife records isolated the calls of individual creatures, but Bernie recorded habitats as a whole. Hearing the interwoven sounds of plants, animals, and landscapes and the complex interplay between the timbres, pitches, and amplitudes, he proposed a remarkable new theory of ecosystem functioning: that each species produces unique acoustic signatures, partitioning and occupying sonic niches such that the singing of all of the creatures in a healthy ecosystem can be heard, organized like the individual players in an orchestra.

It cannot be overstated how impressive and important Bernie’s library is. There were no mentors, no guides for what equipment to use in extreme weather, no instructions for how to capture the subtle sounds of snow falling, the depth of a glacier cracking, or the whispers of wolves. Nor was there the scientific language to describe what he was hearing and what it revealed. Bernie and his colleagues had to figure all this out themselves, inventing a new scientific field called “soundscape ecology.”

Bernie’s soundscapes were full of epiphanies about the origin of our own culture and music, about the profound connectedness of creatures, and about the unseen tolls of human activity. Fifty percent of the habitats in Bernie’s archive no longer exist due to habitat destruction, climate change, and human din.

In recent years, Bernie has turned his attention to conveying the profound beauty, change, and peril of these soundscapes to a wide audience through books and artistic collaborations, including a 70-piece symphony composed with Richard Blackford for the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and an exhibition celebrating nature’s vast and imperiled musical ensemble with Fondation Cartier in Paris.

His work reminds us how much we have to gain by being quiet, listening, and saving the world’s animal choruses — and the gravity of how much animals and humans alike have to lose if we do not.

Bernie recorded the biophony of Osa Peninsula in Costa Rica in 1989. At the time, the site consisted of thousands of acres of old forest (left). In subsequent years, the forest was largely clear-cut and covered with a grid of logging roads. In 1996, he returned and recorded the same site again (right). The chorus was silenced. “One of the major contributions to the field of soundscape ecology will be precisely these types of assessments, planned from the outset with careful attention to calibrations of microphones, recorders, input and output levels, and appropriate metadata such as weather, date and time, microphone placement, and GPS information,” Krause writes in Voices of the Wild. (Courtesy of Bernie Krause.) These two spectrograms capture the sounds of Lincoln Meadow in California before and after a selective logging operation. In the first 15 seconds, recorded by Bernie in June 1988, you hear the biophony’s dawn chorus, including the voices of Lincoln’s sparrows, Williamson’s sapsuckers, pileated woodpeckers, golden-crowned kinglets, robins and grosbeaks, squirrels, spring peepers, and numerous insects. The second clip was recorded a year later after the logging took place. The timber company promised local residents that there would be no environmental impact from harvesting only select trees from the site instead of clear-cutting. Bernie’s recordings showed that was far from true. The once rich biophony was nearly silent, punctuated only by the sounds of a stream and a hammering sapsucker. (Courtesy of Bernie Krause)

This episode contains music and recordings are from Wild Sanctuary.

Bernie Krause’s Recommendations:

The Soundscape by R. Murray Schafer

A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson

The Invisible Pyramid and The Star Thrower by Loren Eiseley

Black Nature by Camille Dungy

How to Fly and The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver

Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez

Desert Solitaire and The Monkey Wrench Gang by Edward Abbey

Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner

The Abstract Wild by Jack Turner

The Overstory by Richard Powers

Nature and Madness and The Others by Paul Shepard

Music by Cosmo Sheldrake

Love This Giant by David Byrne and St. Vincent

Become Ocean by John Luther Adams

It’s OK To Cry by SOPHIE

Listen & subscribe to When We Talk About Animals: Apple Podcasts | Soundcloud | Spotify | Stitcher | Google Podcasts