President Kennedy & First Lady Jackie in Dallas, Nov. 22, 1963 (Photo: AP)

President Kennedy & First Lady Jackie in Dallas, Nov. 22, 1963 (Photo: AP)So Let It Be Rewritten

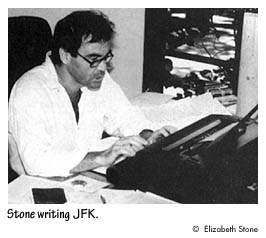

Returning to the topic of history on film — and specifically to the three-hour+ director’s cut of JFK (1991), written and directed by filmmaker and lecturer Oliver Stone — let’s look at several scenes from the movie that highlight a particular point I have lately uncovered.

That point happens to be the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and the subsequent investigation into his death not only by the Warren Commission, which issued their findings in a detailed and largely discredited report (in the film that is, not in real life), but also by the sham conspiracy trial of a New Orleans businessman named Clay Shaw.

In the movie, this forlorn, effeminate soul (portrayed on screen by Tommy Lee Jones in a short curly-blond wig) is the central figure in an elaborately conceived, highly convoluted plot to kill the president for an untold and ever-expanding number of reasons. It juxtaposes the slippery personality of Shaw with the upright, upstanding district attorney Earling Carothers “Jim” Garrison (Kevin Costner), also of New Orleans — a classic Hollywood setup, the confrontation of “good” versus “evil”: the advocate for truth and justice against the perpetrator of sinister plots.

What struck me, while watching the film again after so many years removed from its original viewing date, was Stone’s allegorical representation of the dedicated Garrison as a firebrand, a modern-day St. Peter or St. Paul (he could go either way), working alongside his “crack” team of investigators embodying the eleven remaining Apostles.

The same could be said of the other participants in the drama, including the secretive “X” (Donald Sutherland), a character based, according to Stone, on several real-life military figures, or a composite of the same. There’s New Orleans Assistant D.A. Bill Broussard (Michael Rooker) who slowly but surely loses faith in what Garrison is preaching. And what of Garrison’s long-suffering wife, Liz (Sissy Spacek), who basically whines and complains about her husband’s neglect of her and their children throughout the entirety of the picture?

The real Jim Garrison — stoic, cold and tall of stature — makes for a ghostly cameo as Chief Justice Earl Warren when he interviews a sweaty, tension-filled Jack Ruby (Brian Doyle-Murray), in prison for the killing of Lee Harvey Oswald (Gary Oldman). In the film, and in real life, Ruby died of complications shortly after being granted a retrial for the assassin’s murder.

In the extended scenes tacked on to the film, Stone allows for fearful representations of Jack Lemmon as gumshoe Jack Martin and a vicious Ed Asner as Guy Bannister, a key member of the team that conspiracy theorists claim included government officials at the highest conceivable level (all the way up to then-Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson, if my reading of their theory is correct). This, along with numerous unexplained deaths of various and sundry participants, key discredited witnesses, muddled motivations, etc., and so forth, form the backbone of what turns out to be a paranoid’s worst nightmare.

Indeed, there is a veritable narrative mess at Garrison’s summation. The conclusions he draws at trial have no basis in verifiable fact and are hinged purely on conjecture. The case against Shaw and the deceased David Ferrie (a super-hyper Joe Pesci), who died under “suspicious” circumstances, we are shown, is dismissed and a mistrial is declared. The real villains are set free, to be let loose on unsuspecting and freedom-loving Americans; their “crimes” against the public trust going unpunished.

The Christ Connection

Stone took as his model not so much history as hagiography. His main sources for JFK remain Garrison’s book, On the Trail of the Assassins, as well as Crossfire: The Plot that Killed President Kennedy by Jim Marrs. But the source that has gone unmentioned in most movie reviews is the Holy Bible. Stone based his fictional account of the investigation into Kennedy’s death on the Acts of the Apostles, notably the follow-up to Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection, and the subsequent fate of the Apostles as seen through Garrison’s eyes.

Indeed, all the characters have their corresponding associations with personages from the New Testament, i.e. the various gospels of Mark, Matthew, Luke and John. In addition to which, the movie asks audiences to take a giant leap of faith as the crusading lawyer and champion of righteous causes, Jim Garrison, confronts the villainous cretins in court.

One of the prosecutors, Broussard, is called “Judas” for his desertion to the other side. It’s every man for himself in the end, with Kennedy (the Christ-like figure par excellence) dying so that others might believe that he was pursuing the “good work” in preventing the military-industrial complex from taking over the U.S. government.

President Kennedy is the elusive Christ figure — and despite his reputation with the ladies, a basically good and decent man who was undone by his political adversaries whose agenda ran counter to his own. That agenda, in the screenplay according to Stone, involved Kennedy’s plan to scale back the U.S. military’s commitment to wage war wherever and whenever it felt the need. In the movie, it was Vietnam.

In today’s world, what with all the turbulence the Trump Administration has been experiencing of late, and with theories about collusion with the Russians and such, perhaps Stone’s crackpot viewpoint is not so farfetched after all.

Still, the very notions the film JFK interjected into the conversation and espoused when the film was originally released, and onto which historians have poured their most extensive research into debunking, practically beg to be reconsidered anew in light of current situations. The very thought of a mass conspiracy on an unprecedented scale was unthinkable then, and remains so to this day. Yet, the idea that LBJ, the FBI, the CIA, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff were in cahoots together in a plot to assassinate the president of the United States is the stuff of Shakespearean drama.

To reiterate, D.A. Garrison, by default, was either Peter or Paul, depending on the filmmaker’s whim and as dictated by the needs of the screenplay. He is a defender of the faith as well as a detractor of the faithless (down to his own wife), an apologist and an instigator, but ultimately a true believer. However, Garrison and his team must operate behind closed doors, much as the Apostles did when they went into hiding after Christ’s death. Their mission: to prove that Kennedy/Christ was killed for the wrong reasons; that his memory will be preserved in their work and in the work of others; and that the Kennedy/Christ legacy can live on in the “retelling” of the story — that is, in the newly formed Gospel of JFK, as told by Oliver Stone — for generations to come.

One thing the movie got right was its use of the complete 8mm Zapruder film, which was shown for the first time at Clay Shaw’s 1969 trial for conspiracy and murder (with LBJ and company cited as “accessories after the fact”). The film all-but embraces, with good reason, what critic David Thomson emphasized as “rampant paranoia.” It attempts to connect Dwight D. Eisenhower’s historic warning about the “military-industrial complex” with Kennedy’s death, the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, and the rising Communist threat in Southeast Asia, along with JFK’s arrival in Dallas (an allegorical allusion to Christ’s “triumphant” entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday).

Actual newsreel footage is shown of the young president in his prime with his alluring First Lady, who carries a bouquet of red roses (flowers associated with the Virgin Mary) on that fateful November 22nd day in 1963; this is juxtaposed with black-and-white recreations of alleged incidents in the JFK narrative, credited to director Stone and journalist and teacher Zachary Sklar. We then see a brief portion of the Zapruder film and hear broadcaster Walter Cronkite’s breathless reporting of the assassination.

Cut to Garrison in his office and Cronkite’s teary-eyed pronouncement of Kennedy’s passing. Flashes of Lee Harvey Oswald’s face connect him with the murder. Garrison and his staff are gathered in the office, surrounded by law books — i.e., the Apostles, none of whom were present at Christ’s crucifixion, at the first gathering after His death, among the books of the Old Testament which attest to their authority on the matter.

The law library stands as an equivalent monument to the rule of law, the symbol of our government, of the courageous men and women dedicated to the unvarnished truth and the ways of attaining that truth, no matter the cost to their reputation or personal integrity. They are “witnesses” after the fact of Kennedy’s death; they see Oswald’s execution by Jack Ruby, as Kennedy’s funeral procession flashes by before them (and us).

Next, there is the announcement of the Warren Commission. Three years later, in November 1966, we flash forward to where LBJ “seeks $9 billion in extra war funds,” as seen in the headlines of the Washington Post. Little tidbits of information are intercut into the narrative, raising suspicions about minor events, those so-called “unusual occurrences” that “don’t add up,” such as the clean-cut, clean-shaven vagrants arrested the day of the assassination.

The three lawyers, Garrison, Broussard and Lou Ivon (Jay Sanders), meet in Lafayette Square in New Orleans. They remark on the proximity to one another of several government office buildings: the Office of Naval Affairs (which is now the U.S.P.O.), the Office of Naval Intelligence, the FBI, the CIA, the Secret Service — all in one plaza and inviting comparisons to Biblical claims of propinquity with regard to Pontius Pilate’s palace, King Herod’s abode, the Council of the San Hedrin, the Mount of Olives, the Garden of Gethsemane, and Calvary.

The Greatest Story Never Told

During the first third of the film, people come forward and state their case — they give testimony, to put it plainly, about what they saw and heard, adding to the available source material as hearsay evidence, or supposed “eyewitness testimony.” The sweaty, porcine physiognomy of shady lawyer Dean Andrews Jr. (comic John Candy in dark shades, naturally) discusses his refusal to act as Oswald’s defense council over dinner with a skeptical Garrison.

After further inquiries, Garrison and his team unite with two or three other colleagues over a noontime meal to talk among themselves about the hoboes that were arrested. Assistant D.A. Susie Cox (Laura Metcalf) joins the group. She is the official record keeper of events, the Mary Magdalene model and transcriber of the spoken word. It is here that Oswald is talked about as the prime suspect by default due to the plethora of contradictory information swirling about him.

This extended restaurant sequence serves the purpose of questioning whether Oswald had acted alone in carrying out his crime (the notorious “Lone Gunman” theory) or in conjunction with other co-conspirators.

In the next scene, we are privy to a recreation of eyewitness accounts of what several individuals claim to have seen at Dealy Plaza — i.e., Calgary, or Golgotha (“the place of the Skull”), where our Kennedy/Christ died. Smoke rises from the grassy knoll; a man with an umbrella is spotted; there are shadowy figures behind a fence; a pickup truck is mysteriously provided by the Secret Service; and the man behind the wheel of that truck is none other than low-level mobster Jack Ruby before he killed Oswald.

Four to six shots ring out from behind a picket fence. It is here, after these events take place, that a grim-faced Chief Justice Warren (ironically, the real Jim Garrison) interrogates jailbird Jack Ruby behind bars, a soon-to-be-martyred victim to the “cause.”

All these pop culture references have been interspersed throughout the picture in order to plant seeds of doubt in the viewer’s mind as to what actually transpired before, during and after Kennedy’s death. These and similar scenes will recur at preordained junctures.

We are then taken to the Texas Book Depository building that overlooks Dealy Plaza (the proverbial “scene of the crime”). Lou and Garrison will attempt to recreate Oswald’s dastardly deed with the use of a replica of the infamous 6.5mm caliber Carcano Model 91/38 rifle. Their conclusion: it would be impossible, even for an experienced marksman, to accurately fire off three consecutive shots in the 5.3 seconds it took to kill President Kennedy. And the manual loading Carcano had a defective scope at that! But the plain fact remains that Kennedy was killed. There is speculation as well as to the actual number of teams (three, to be exact) it would take to be able to execute the crime at strategic vantage points.

After another meeting of the faithful, this time in D.A. Garrison’s spacious living room, Susie Cox/Mary Magdalene reports on a bogus “Oswald” pretending to test drive an automobile when his wife, the Russian-born Marina Nikolayevna, had previously testified to the Warren Commission that her husband did not have a license. During Susie’s account, another “Oswald” is caught practicing at a firing range, while a third “Oswald” happens to be spotted in Mexico.

Next, the viewer is treated to the LIFE magazine cover which highlights the purportedly doctored photograph of Oswald holding aloft his Carcano rifle. The real (or “reel”) Oswald complains that the man in the photograph isn’t him at all, but an imposter. Deceit piles upon deceit. Garrison begins to believe that Guy Bannister (Ed Asner) created “Oswald” for the sole purpose of using him as a patsy to cover up their real intentions: the planned execution of JFK. This is the second meeting of the group (the Apostles) before the Via Dolorosa, leading up to the Via Crucis or the Way of the Cross.

To further the religious connotations, Garrison goes to interview the mysterious “Clay Bertrand,” in actuality local businessman Clay Shaw. The interview takes place in Garrison’s office on Easter Sunday — resurrection day in Christian theology, telegraphing the eventual resurrection of the Kennedy case. Clay denies any and all knowledge of the “sordid cast of characters” Garrison associates him with, to include the oddball Davie Ferrie, the gay hustler Willie O’Keefe (Kevin Bacon), the Cuban ex-military types, et al.

Garrison accuses Shaw of having gotten away with Kennedy’s murder, a statement that profoundly offends Shaw. Garrison’s assistant Broussard comes between the combatants before either man comes to blows.

Shaw wishes everyone a Happy Easter and departs in a characteristically lighthearted mood. In response, Garrison quotes a line from Shakespeare’s Hamlet: “One may smile, and smile, and be a villain.” The next move is Garrison’s.

(End of Part Three)

To be continued…

Copyright © 2017 by Josmar F. Lopes

Advertisements