Introduction to “Reel” Life

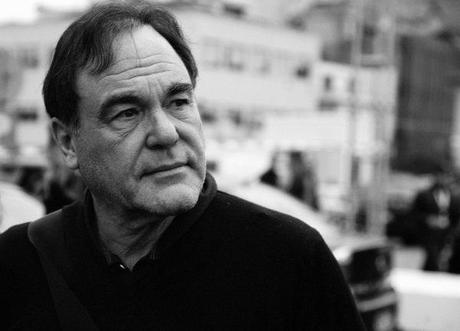

Director Oliver Stone (scmlmag.com)

The fall 2013 issue of Cineaste includes a feature-length article by the magazine’s consulting editor, Dan Georgakas, of a ten-part documentary series entitled “Oliver Stone’s Untold History of the United States: The Course of Empire.”

Known for his faux-biographical depictions of Presidents John F. Kennedy (JFK), Richard M. Nixon (Nixon) and George W. Bush (W), as well as imaginative recreations of events and personalities in such films as Salvador, Platoon, Wall Street, The Doors, Born on the Fourth of July and World Trade Center, screenwriter, producer, director and lecturer Oliver Stone has also coauthored a 750-page companion book of the documentary with professor of history and director of the Nuclear Studies Institute at American University, Peter Kuznick, who contributed to the series’ script.

In the book and documentary (to be issued on DVD in March 2014), ex-Vietnam veteran Mr. Stone attempts to correct our perceptions about the numerous inaccuracies that have been foisted upon Americans with regard to their own history. Among the themes associated with his five-year project is one where Stone maintains that we have been thoroughly misled about U. S. involvement in a variety of international conflicts, beginning with (but not limited to) the Second World War — ergo the Untold History aspect of the title.

From such seminal ideas as Manifest Destiny and American exceptionalism to this country’s later foreign policy with respect to Korea, the Cold War, Vietnam, Iraq and other trouble spots around the globe, the idea of a secret basis to, or “between the lines” reading of, American history is challenged and refuted by Mr. Georgakas. To begin with, he charges the narrative of Stone’s documentary with, among other things, “a penchant for interpreting historical decisions as dependent on personalities,” as if all it took to plunge America into all-out war were the bull-headed decisions of a few charismatic leaders with gutsy feelings in their bellies.

Georgakas then takes the director to task, mostly over his use of Hollywood fiction films (“A troubling and surprising aspect”), which serve as visual manifestations of many of the events discussed and analyzed in Stone’s multipart series. When viewing these movie clips, Georgakas contends, viewers might mistake them for the unvarnished truth — or worse, as indisputable evidence of the validity of Stone’s claims. Further, he goes on to cite an intrinsic problem that exists in this country, in that many people tend to get their history (along with their facts) from movies, television and online news services — which as many of us know, aren’t always the most dependable and, more often than not, have agendas of their own to push.

This argument raises the whole issue, then, of whether anyone — be they American or German, British or Chinese, Russian or Lithuanian — has the temerity to portray history, or past historical events, in forms (that is to say, Hollywood films) that are fundamentally at odds with legitimate or traditionally-accepted means; thereby making said forms subject to re-interpretation by a single if not a whole host of individuals — in Stone’s case, by a radical filmmaker with his own agenda to pursue.

To my understanding, this defeats the purpose of having historians, i.e., persons trained and experienced in recognizing the differences between fiction and fact, act as custodians of the past. As we are keenly aware, it’s a widely held notion that “history is written by the victors.” What this statement ultimately reveals, however, is that events leading up to those victories possess a built-in degree of ambiguity. In other words, they are dependent exclusively on the writer’s limitations as an educator or historian, along with that individual’s choice of material from among a wealth or lack of available sources, as well as specific knowledge of events.

More to the point, an element of trust must exist between the reader and the writer in accepting this individual’s finished output. If that trust is broken or disturbed, or never existed in the first place, then the fault lies with the writer and his work. But if that trust can be established at the outset and kept intact throughout, only then can we be assured of a fairly objective and reliable reading of the past — given the nature and type of quantifiable evidence relied upon.

George, Nicholas and Wilhelm book cover

An excellent example of this can be found in Miranda Carter’s richly detailed book, George, Nicholas and Wilhelm: Three Royal Cousins and the Road to World War I, wherein extensive correspondence between the three titular heads of state, their personal recollections and individual diaries and memoirs, in addition to historical records, documentation, memoranda, obscure notations, newspaper accounts, period writings, and other primary-source material helped to elucidate the topic in a thoroughly satisfying manner.

This is where reader, writer and editor Mr. Georgakas, and screenwriter, director and lecturer Mr. Stone, part company, in that the main bone of contention is the latter’s use of Hollywood fiction films as stand-ins for the requisite evidential source-work; or, to put it brusquely, the introduction and incorporation of non-traditional (read: illegitimate) forms that are hardly the last word in authenticity or accuracy.

By that reckoning, Stone’s past record of cinematic accomplishments is not exactly what Georgakas, or anybody else for that matter, would term a fitting background for this kind of “complex social, economic, and political” endeavor, thus squelching the needed trust factor from the start.

When in the “Course” of Human Events

I have always been fascinated by history. I did, in fact, major in the subject at Fordham University, while I continue to espouse a thoughtful and constantly evolving interest in Hollywood films with stories about individuals, personalities and themes related to the past (Lawrence of Arabia, Lincoln, Saving Private Ryan, Glory, Patton, The Aviator, The King’s Speech, El Cid, and numerous others). This is what attracted me to Cineaste’s piece and director Stone’s prospective thesis.

The magazine itself has even devoted past issues to the subject. In fact, their spring 2004 edition included a “Film and History Supplement” that was published with “special support provided by the Academy Foundation of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.” The editors of Cineaste, as well as this author, concur with and categorically accept the notion that film can bring clarity and purpose to historical subject matter in more entertaining ways than traditional methodologies can.

When I was a teacher of English as a Foreign Language in Brazil, I developed a course entitled “American History and Culture through Film.” The course’s aim was to chart the path the country took to become an independent nation and world power, by linking this objective to various Hollywood films that dealt with the same concerns. Commentaries from historians and movie critics, in conjunction with film reviews, critiques, pictures and clips would be shown in support of the assigned reading material. The text that was used, An Illustrated History of the USA by Bryn O’Callaghan (published by Addison Wesley Longman, Ltd., 1990), explored the “development of the United States from its origins as a land inhabited by scattered Amerindian tribes to the culturally diverse but united country that we see today.”

Reflecting back on my course as it relates to Georgakas’ article, I realized, to my surprise, that perhaps I had been performing the same function back in my pedagogical days that Stone was attempting to perform today — and via similar methodology. The difference being, however, that back then I claimed no right to historical accuracy in my use of Hollywood fiction films. By providing, where needed, the appropriate explanations and clarifications to what my students were viewing, the readings on culture and history assigned them worked hand-in-hand with the images I intended to show. Still, numerous questions came to mind as I was planning and preparing my course for presentation.

As an indication of this thought process — and, to be perfectly honest, the thought processes of my students — I have listed many of the questions below. The answers to these questions have been provided where feasible, although for the most part they remain open-ended, which, for all curious and supportive teachers everywhere, is as it should be.

To begin with, what is history? What is the difference between what we call “history” and a simple “story” — a word derived from the same Latin and Greek roots? Why do we study history? How is history different from, say, myth and legend? For one thing, history is the study of past events, or events known to have occurred in the past. We may also define it as a search for the truth. The reason we study it is self-evident: to understand how and why these events occurred and, if possible, avoid a repetition of those mistakes that led to their occurrence.

Discounting the influences of religion, how is history conveyed and preserved? One of the ways that history can be conveyed is by oral means, which is not the most practical or reliable. One of the ways it can be preserved is by the written word, which turns out to be quite practical, but can also become unreliable. Other methods of conveying and preserving history are visual, i.e., through pictures, photographs, film, TV, video, and digital, electronic or hardcopy formats.

Frame of Zapruder’s 8mm film (usatoday.com)

If we look at one of these methods — film — we can see that film is a combination of many forms of preservation. We know that film is a visual record of an event (for example, Abraham Zapruder’s 8mm footage of the Kennedy assassination). The event can be current or one that took place in the past. A documentary, then, is a real-life record of an event or occurrence, either currently or in the past. We also have fictional records of an event, which can be defined as a recreation of the past, albeit one where the narrative is subject to embellishment so as to incorporate a specific story line or plot. Representations of future events, or events yet to have occurred, are labeled science fiction. To this we add a level of speculation about the future and what that future might hold.

When filmmakers decide to recreate the past on screen, it’s instructive to ask how one can transform an event that has already taken place into one that has yet to occur. To put it another way, when we see a cinematic representation of a past historical event, do we ever wonder how the past could suddenly have become the present? Upon completion of our viewing of a film, how often do we notice that the present has now become the past? Why is that important? What influence does the past have on current events? How about on future events?

As we ponder the range of possibilities implicit in the above queries, keep in mind George Orwell’s famous warning from his novel 1984: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.” The implication here is that by controlling the past one can also control both the present and the future.

Film, as far as we know, is the end-product of a vision of many people, a collective vision of a talented and diverse group of individual mind-sets. Among the individuals involved with that collective vision are the film’s director, producer and screenwriter, the production designer and art director, the costume designer and cinematographer, the soundtrack and Foley artists, the composer and special-effects artists, and dozens upon dozens more. How do we bring all these disparate elements together into a coherent whole in order to tell a viable story? For that matter, what story do we want to tell? How does one choose a story from the past from among so many stories available to us?

Here’s a little exercise you can do in the privacy of one’s home or apartment. Take an incident from your childhood, say, your first day at school. Now think about the main characters involved in that incident. Next, take the main events of your story and telescope them by mapping out a timeline of events. Narrow the focus down to the essential ingredients; try concentrating on one specific event at a time, one major highlight of your tale that will help tell the story visually. What events do you use? Which characters do you include? Which ones do you reject? Think about the time-lapse of events, what we call foreshortening, as a way of telling your story. Do you want a visual representation of these events (“plain vanilla”), or a verbal and visual one (“mixed bag”)? How would you present them and in what order?

The next part is more thought provoking. From the above mental exercise, determine if your final product will be a “true” representation of the past or a fictionalized account. Could actors really take the place of real people in your story? Who would you hire to play the major roles? Who would be the lead? Who would direct the film version? Who would write the script? Compose the score? Shoot the footage? Decorate the set? So much to think about, so little time to spare. This is the dilemma of all those professional story-tellers out there we call filmmakers — welcome to the club!

Revisionist History and the Distance Problem

What do we mean by revisionist history? Theoretically, revisionist history (also known as historical revisionism) is the process of finding inaccuracies or fallacies in the historical narrative or record and making corrections to it. Hand-in-hand with correcting the narrative is the added difficulty of having to challenge people’s long-held views of the past and their inability, as we perceive it, to concede to their revision.

Is this what is meant by a “modern interpretation” of past events, for example, the aforementioned Kennedy assassination and the supposed “lone gunman” theory (JFK)? What about the plot to kill Adolf Hitler (Valkyrie), or the Watergate scandal (All the President’s Men), or Iran-Contra (Clear and Present Danger), or the search for Bin Laden (Zero Dark Thirty), or any number of past occurrences?

As a prospective movie-maker, a potential Oliver Stone in the making, can you get away with revising the past — and to what degree? What’s to be gained by doing so, and is it right to engage in revisionism for artistic purposes, the so-called “art for art’s sake” excuse? How can we escape the dangers of historical revisionism? Shouldn’t we present these events as they really were? That’s the province of investigative journalism, isn’t it, of the kind that figured prominently in the movie, All the President’s Men.

Let’s take the stories of individuals from the past. Some recent film subjects include King George VI, Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Nelson Mandela. These are all famous subjects who made their lasting mark in the past. Distance from a subject can bring with it a kind of physical as well as mental distortion.

Try this experiment: take a small object — your smart phone, for instance — and place it in front of you. You can still read the phone’s contents, can’t you? Now place the phone farther and farther away from you. It becomes progressively more difficult to read the contents, doesn’t it? Bring it closer to you, and it becomes clear again.

Let’s look at a postcard, any postcard, of your favorite haunt or vacation spot. Postcards have a sharper focus “close up” than they have when held at a distance from one’s prying eyes. One can’t read the inscription on the back when the postcard is away from your field of vision. One must rely on one’s memory of what the inscription actually says. But memory is a fragile thing, as we know, and many times the memory of what was said or written fades into obscurity. Now you can understand and appreciate what distance can do to history. This is what we call the distance problem.

This experiment can be applied to politics as well as to history. Do politicians really believe that their constituents will remember what they promised to do for them once they get elected? With the invention of the Internet and YouTube and other electronic devices and means of preservation, we now have the ability to instantly fact-check what those same politicians have promised and thus correct the historical narrative, i.e., those inaccuracies and fallacies, not to mention distortions, of the recent past that were once taken for granted. It’s a dream come true for historians.

To Film or Not to Film

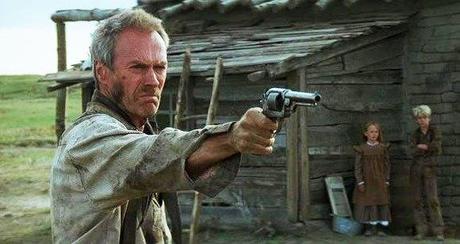

Clint Eastood as William Munny in Unforgiven (fanpop.com)

Which films can be used to describe the historical narrative? While my course was basically concerned with films on or about American history, any halfway decent representation of the past can be utilized as long as one prefaces their use and content with the following caveat: “This is only a fictional reenactment of the events or persons depicted” — that is, “It ain’t necessarily so, folks.”

Some subjects have an enormous quantity of available footage to select from (Westerns, Lincoln, the Civil War, and Vietnam). Others have a very limited field from which to choose (the American Revolution, FDR, and Nixon). While most of the films can be about actual historical events or situations in the past, some are purely fictional representations (Gone with the Wind, The Manchurian Candidate) with factual aspects thrown in. Nevertheless, I attempted to highlight as much of American history and culture as possible in my choice of movies, without boring the students. Since I was dealing with a Brazilian mind-set, I chose popular films about subjects and personalities that Brazilians had a general knowledge and curiosity about.

Along the same lines, what is a film genre? Why do we classify movies by subject? Is it easier or more difficult to place a film story in a genre? What are the conventions of a genre? Let’s have a look at a typical American genre, the Western. What are the conventions of a Western? Well, there’s a good guy, a bad guy, the chase or pursuit of one party after the other, the posse (the ones who do the pursuing), and the conflict. There’s also the resolution of the conflict, known as the duel or shootout; the scenery, the horses, the Indians, the girl, and the reward.

Most people would be surprised to learn that most of the above conventions never took place, or if they did occur it was not in the manner represented on film. An illustration of this point is the story of Wyatt Earp. Before 1900, Earp was almost a totally unknown figure. Then, a story teller took his tale and transformed it into a dime-store dreadful called Frontier Marshal, which made Earp’s name a legend. Afterward, the legend became myth and the myth became one of the most famous Wild West stories of all time. This bred other tall tales, including those of Jesse and Frank James, Billy the Kid, Annie Oakley, Buffalo Bill and a myriad of others.

John Wayne & James Stewart in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

There are numerous examples of films that discuss how fictitious events become fact. The “facts,” such as they are, get converted and distorted into legend, which later become myth. John Ford’s Fort Apache, and especially The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, bring this facet of myth-making to practical and disturbing life. A modern interpretation of this phenomenon is present in Clint Eastwood’s unforgettable film, Unforgiven, in which the lead character, William Munny, is faced with having to live down his murderous reputation, while simultaneously being challenged to live up to that same reputation in order to collect a monetary reward at the end.

This brings us back to the essential problem of history and the historical film, which can be encapsulated in the famous line spoken by one of the reporters covering the funeral of the John Wayne character, Tom Doniphon, in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. After listening to the real version of events surrounding the shooting of the notorious killer, Liberty Valance, by former governor of the state and U.S. Senator Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart), the newspaper man unhesitatingly burns his notes and declares to Stoddard, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” which is exactly what many historical films do.

And no history remains “untold” for very long, as we shall see in Part Two.

(End of Part One)

Copyright © 2014 by Josmar F. Lopes