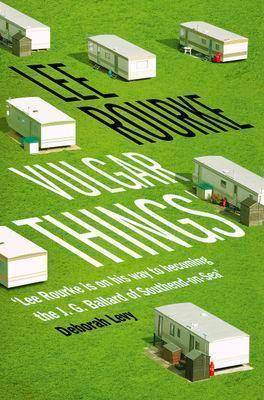

Vulgar Things, by Lee Rourke

When I was in my mid-20s I found myself for a while living in a rented room after a serious breakup. I lost my job about the same time, and then one night the flat was burgled and pretty much everything I had was stolen. I was left with little more than the clothes I was wearing while out that evening. At the time it was a bit crap, but I was young and I was lucky, and so my life fitted into a neat narrative where I took everything falling apart as a chance to take a different direction and build something better second time around.

Jon Michaels is a recently divorced editor in a small publishing house who’s laid off in the opening chapter of Lee Rourke’s Vulgar Things. As he drinks to celebrate and forget, he gets a call from his brother telling him that their odd and reclusive Uncle Rey has killed himself and as the brother is too busy Jon needs to go down to Canvey Island in Essex and clear out Uncle Rey’s caravan.

Jon’s situation and my own have some broad parallels, though no more so than many other people’s stories. The opening here is a device – Rourke needs Jon in a state of breakdown where he’s looking desperately for something real to hold on to (and which he disastrously tries to find in the detritus of his uncle’s life). Still, whatever meaning books carry is as much a product of what we bring to them as what’s between their covers, so I thought the anecdote relevant. Besides, I was struggling to open this piece.

Jon makes his way to Canvey Island, an isolated spot off the Thames Estuary built from reclaimed land. It’s about 30 miles from London and apparently used to be something of a seaside resort, but those years are decades past and now it’s largely industrialised and might as well be 300 miles away. What’s extraordinary here, and what’s undoubtedly the best aspect of this novel, is quite how good Rourke is at evoking this landscape.

I’ve forgotten just how flat and eerie the island is: the idea that the land beneath my feet actually lies below sea level – the estuary looming high up behind the sea walls – becomes more worrying with every step. The sky above me, massive and grey, stretched to its limits, bears down on the island. I look over to the large oil refinery that dominates the immediate horizon to my right. There are people in hard hats over there, bobbing about, doing stuff with popes and machinery. Maybe that’s where everybody is? Working hard at the refinery.

I can hear something, off in the distance. It comes to me suddenly. There it is, the rumble of an oil tanker’s engines ahead of me out on the Thames, a constant baritone, its vibrations felt from the tip of my toes to the hair on my head, all around me, quivering on my tongue and through the fine hairs in my nostrils. There it is again, a slow, aching, constant rumbling, from somewhere within the water above, making slow progress towards Tilbury. I stop dead and listen to it pass, until it fades from my range and the tingling subsides within me.

Uncle Rey’s caravan is by the Lobster Smack, a real Canvey Island pub which is something of a local landmark. The caravan is a rundown affair piled high with pages from a manuscript Uncle Rey seems to have been working on as well as videos and DVDs forming a decades-long video diary of sorts (strongly reminiscent in form and content of Staniland’s diary in Derek Raymond’s He Died with his Eyes Open). In an adjacent shed there’s a high-end telescope. Rey seems to have spent his time gazing at the stars, struggling to write some book that never came near to being published and recording hour after hour of, well, of what exactly?

Jon meanwhile is in a near-permanent alcohol-induced fug and has become fixated on a woman he sees on Southend Pier whom he thinks needs rescuing from some uncertain “they”. What follows is a sort of confused detective story, as Jon tries both to understand the traces his uncle left behind and to track down this woman so that he can save her, whether she needs saving or not.

Rey’s manuscript, itself titled Vulgar Things, is a confused stream of consciousness attempt to somehow rewrite Petrarch’s Rerum Vulgarium Fragmenta (Book of Common Things, or if you prefer, Book of Vulgar Things), which I’ve not read and hadn’t heard of before reading this book. It includes allusions to some sin or crime involving Jon’s own mother who Rey apparently idealised and called his Laura (a Petrarchian reference I utterly missed). Jon takes Laura as the name for his own mystery woman, and so his life and Rey’s become muddled, both of them lonely men pouring all their frustration and desire on a woman who’s as much a creation of their need as she is a person.

What Rey was grappling with, and what of course Rourke himself is grappling with, is how to say something true on a piece of paper. Rey tried to take Petrarch’s words which spoke to him and to somehow make them current so that they were fresh again, but he failed. He wanted to say something real, and spent hour upon hour on tape and DVD-R looking for the words, but he failed in that too. Meaning and redemption both escaped him, and he wasted his years in a lonely caravan engaged on a mad project nobody would ever care about.

I wanted it to reveal everything, in a clear and beautiful language … But I failed to do that, and I’ve spent my entire life talking into this thing, because of it, trying to come to terms with it, trying to work things out, talking, talking, talking, in the hope that one day something real would appear, you know, that crystallised moment when I speak reality … I’ve waited a long time, a whole lifetime, but nothing, reality has eluded me … it doesn’t exist, it doesn’t fucking exist …

Nobody save Jon that is, who comes to realize that he was Rey’s imagined audience. Jon himself however is in little better shape than his dead uncle. He wanders the streets looking for his own Laura and becomes enmeshed with East European organised criminals who he thinks are forcing her into prostitution, though it’s quite clear to the reader that the woman he saw on the pier and the prostitute he tries to rescue are completely different women with only a passing resemblance to each other.

Jon’s mother has no voice here. All we know of her is what Jon and others remember and Uncle Rey’s rantings and digressions. The actual woman is lost from view, hidden somewhere behind Uncle Rey’s idealisation of her. Jon is similarly now denying his Laura’s reality, so blinded by his own need that he conflates different women together into one imagined whole. Early on in the book he goes to a pub where strippers perform for a few quid put in an empty beer glass. He doesn’t see it, but his unasked-for rescue is the same as watching those strippers. Either way it’s men preferring a fiction of a woman to a real one.

If that gives the impression that this is something of a novel of ideas then that’s fair. Rourke is looking here at issues of authenticity, and male gaze is one of several examples. Uncle Rey wanted to say something true, but couldn’t. He wanted to find something transcendent in his Laura, just as Jon does in his, but each instead turned a real person into an imagined one. Perhaps the irony though is that while all of that is interesting, it’s in the description and dialog where Vulgar Things most sings to me.

There’s a rather wonderful self-undermining Wicker Man-esque quality at times to Vulgar Things. Mr Buchanan, landlord both of the Lobster Smack and of Uncle Rey’s caravan, is friendly and helpful but does he have ulterior motives? Everyone seems to know Jon’s business and Canvey Island seems a repository of nightmares and secrets, but is that just Jon’s drink-fuelled paranoia? Jon stumbles across the landscape, drunk and carrying a very solid walking stick which he’s not afraid to lash out with, and it’s hard to avoid the sense that if there’s anyone in the book you’d cross the road to avoid it’s Jon himself.

Vulgar Things isn’t always an easy book to read. Rourke’s style is intentionally flat; Jon isn’t the most sympathetic of protagonists; Uncle Rey’s sections never go on too long but even so are by their nature confused and rambling; and there’s a certain artificiality to the whole which is there to underline the issues of authenticity but can’t help distancing the reader. For all that, it’s a resonant book which brings a rather strange corner of England persuasively life and by its end I felt like I’d personally walked the streets of Canvey Island and nearby Southend, drank in their pubs and been shouted at by their needlessly aggressive locals.

The fact that the novel is an artificial construct isn’t actually as interesting as some current theorists (“cough”TomMcCarthy”cough”) seem to think. It’s always been true, and yet the novel continues. For me, Rourke’s best talents as an author are place and mood – he’s tremendous at both. Uncle Rey would argue that it’s impossible to capture reality on the page, and I suspect so would Rourke, but I’m not sure that matters when what we can capture is impressions as real as any we have in memory.

I’ll end with some pictures of Canvey Island. Here’s the Lobster Smack:

Here’s some Canvey Island caravan homes:

And here’s the Canvey Island strip (beat this Blackpool):

Other reviews

My review of Lee Rourke’s first novel, The Canal, is here. Vulgar Things doesn’t seem to have been as widely reviewed as I’d expect: there’s a rather good one by Essex native Sara Crowley on her blog here; a very interesting one which talks more of the underlying theory from Bibliokept here; and a rather negative review at the Guardian here, which I link to for a different view (the comments argue the writer missed the book’s point, but I don’t think he did – he just didn’t like it). There’s also an excellent interview with Lee Rourke at The Quietus, here. Finally, there’s a short review but with a very good dialog quote at 3:AM magazine here.

Filed under: Rourke, Lee Tagged: Lee Rourke