Do you have a copy of this book? If not, why not?

This book is free to download. This book contains the evidence for the effectiveness of over 1200 things you might do for conservation. If you don’t have a copy, go and download yourself a free one here, right now, before you even finish reading this article. Seriously. Go. You’ll laugh, you’ll cry, it’ll change your life.

Why you’ll laugh

OK, I may have exaggerated the laughing part. ‘What Works in Conservation 2018’ is a serious and weighty tome, 660 pages of the evidence for 1277 conservation interventions (anything you might do to conserve a species or habitat), assessed by experts and graded into colour-coded categories of effectiveness. This is pretty nerdy stuff, and probably not something you’ll lay down with on the beach or dip into as you enjoy a large glass of scotch (although I don’t know your life, maybe it is).

But that’s not really what it’s meant for. This is intended as a reference book for conservation managers and policymakers, a way to scan through your possible solutions and get a feel for those that are most likely to be effective. Once you have a few ideas in mind, you can follow the links to see the full evidence base for each study at conservationevidence.com, where over 5000 studies have been summarised into digestible paragraphs.

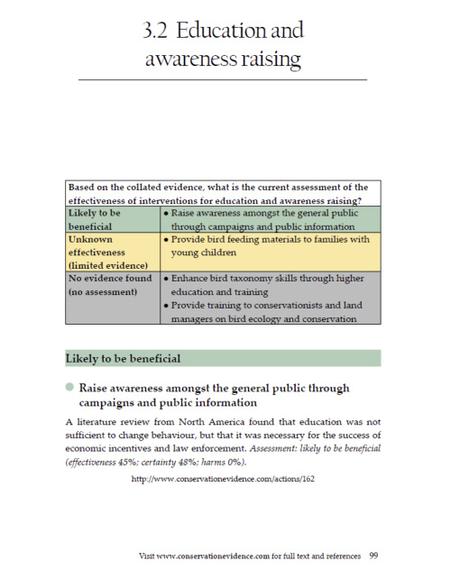

The book takes the form of discrete chapters on taxa, habitats or topics (such as ‘control of freshwater invasives’). Each chapter is split into IUCN threat categories such as ‘Agriculture’ or ‘Energy production and mining’. For each threat there are a series of interventions that could be used to tackle it, and for each of these interventions the evidence has been collated. Experts have then graded the body of the evidence over three rounds of Delphi scoring, looking at the effectiveness, certainty in the evidence (i.e., the quality and quantity of evidence available), and any harms to the target taxa. These scores combine to place each intervention in a category from ‘Beneficial’ to ‘Likely to be ineffective or harmful’.

As all known interventions are included for each chapter, this does lead to some fairly funny interventions being assessed. Want to know if you can encourage birds to shit you a new forest, or protect chicks using discarded snakeskins? Are puppets good surrogate parents for baby bustards, and can you freeze frog sperm? The answers to all these pressing questions lie within these pages, or online. So you might laugh, depending on your humor threshold.

A sample page from What Works in Conservation 2018

Why you’ll cry

If you are a staunch believer that conservation decisions should be based on the best available evidence, some of the chapters might make you cry. For example, of 78 interventions assessed for bats, 48 had no evidence at all as to whether they worked or not, and for a further 12 the evidence was so equivocal, localised or scanty that the intervention was classed as ‘unknown effectiveness’. While an updated version of this chapter is due in 2019 (the original was published in 2013) and might fill in a few evidence gaps, it is clear that the lack of studies testing conservation interventions hampers the efforts of those who want to base their decisions on science.

This problem is not restricted to bats, although they are the most extreme example; when we collate the evidence we see huge ‘knowledge clusters’ such as tests of certain EU agri-environment schemes, and huge ‘knowledge gaps’ such as tests of interventions in the tropics and for taxa such as bats and primates. Researchers could use this book as a way to identify important conservation interventions to test, filling in those gaps and addressing the needs of conservation practitioners. More testing of interventions in general would be positive. A 2005 study of three top journals with ‘conservation’ in the title found fewer than 13% of papers tested a conservation intervention to see whether it worked or not — while this paper is out of date, I’d be surprised if that percentage had skyrocketed since.

It’s not just a lack of studies, but also issues with study quality, that make it hard to quantify the effectiveness of some interventions. Many papers ‘testing’ an intervention were not set up experimentally, but data were gathered opportunistically, often making the results difficult to interpret. Frequently we see that multiple interventions were done at once, meaning that we cannot isolate the impacts of each, or that there is no proper control. For more of a discussion on the problems of study quality when assessing conservation interventions, see this editorial

Why it’ll change your life

Dipping in and out of this book and the associated online resources gives you a taste of a philosophy that is at once practical and optimistic: a philosophy based around conservation solutions. It’s easy to get caught up reading about the latest impending threat to biodiversity, or a complex analysis of which species fail to thrive in human-dominated systems, and to get just a little miserable. To be clear, these studies are also highly important, but relatively little attention in conservation science is given to identifying, implementing and testing solutions (less than 13% of our attention by one count). However, solutions are what we actually need. A focus on solutions is empowering as it involves taking action for conservation, and it may be one of the most important things that we can do to affect real change for biodiversity. Scientists, get out there and test an intervention!

The book is also, like conservation itself, a work in progress. This is the third edition, and the plan is to release a new book each year, with new, expanded and updated material. New material for 2018 comes in the form of chapters on the conservation of primates, shrublands and heathlands, and peatlands, as well as a shorter chapter containing evidence on ways to manage some animal species in captivity for conservation purposes.

The chapter on the control of freshwater invasive species has been expanded to add more species. Chapters replicated from the 2017 edition cover global conservation of amphibians, bats, birds, and forests, conservation of European farmland biodiversity, and some aspects of enhancing natural pest control and soil fertility. Since the book is available for free — and all the material is available online — you don’t need to worry about whether you should wait until 2019 for the next copy (aiming to add an updated chapter on bats, more work on wetland habitats, grassland conservation and more); you can just download what exists now.

Finally, and most importantly for conservation practitioners and policy-makers, this book gives you a way to check quickly what results have been found so far for an intervention that you might be thinking of doing. Checking this book — and the associated online content — is a simple, yet powerful way to ensure that your work is evidence-based, and to choose the interventions that are most likely to work in conservation.

So, once again, if you don’t have a copy, it’s right here waiting for you.

Claire F. Wordley, Conservation Evidence, University of Cambridge