According to the last figures made available by the USDA, the number of American hop farmers jumped considerably from 68 in 2007, just as craft beer was starting to become more mainstream, to 166 in 2012. Today's number isn't readily available, but based on how often local and state media covers some aspect of farmers growing hops, it's safe to assume it's grown just as fast.

Which is good, because craft beer is going to need those hops. But in order to fulfill the requirement of producing enough beer to meet 20 percent market share by 2020, there's still work to be done.

From building the infrastructure to choosing hop varieties, the country needs more farmers, more hops and more investment to make it happen.

A first step to address decreasing hop yields is simply adding more farms, especially considering the American hop market will need about 12,000 more acres by 2020 to fulfill the need of the nation's craft brewers, according to a presentation made by Loftus Ranches' Patrick Smith at this year's Craft Brewers Conference. That's not an inexpensive proposition.

A 2015 study by Washington State University listed a 600-acre farm as an ideal example for the Pacific Northwest based on a range of agricultural, economic and business practices. That size is nothing to scoff at: 600 acres is roughly what California, Colorado and New York have strung for harvest in 2016 combined. Michigan is estimated to have 650 total acres strung in the state.

Whether that 600 acres is realistic given available land for agricultural pursuits is another discussion all together. The average Yakima Valley farm is 450 acres.

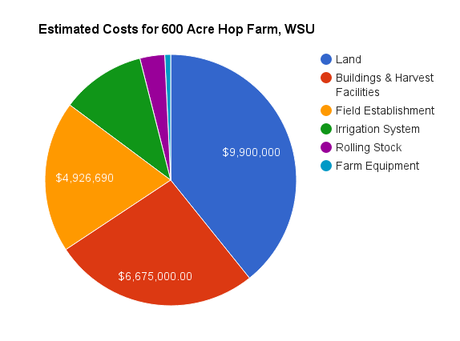

All the same, to create that 600-acre farm, the estimated investment would be in the range of $23 million:

To produce the amount of hops necessary, that size farm would need to be created 20 times over, a total cost of nearly $500 million.

A similar cost was also recognized by the Brewers Association, which even admitted that estimate may actually be low due to rising labor costs, infrastructure and other factors. However, the cost is a shared one, as BA economist Bart Watson noted: "Hop contracts serve as a promise of future payments and guarantee growers and dealers a return on their investments." In addition, the overall cost to grow a pound of hops - depending on variety - may be in the range of $1 to $1.50 in the coming years, according to one estimate.

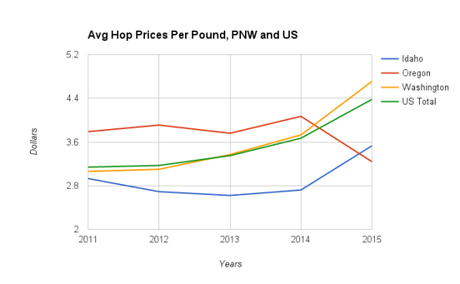

Achieving that return is becoming slightly easier thanks to rising hop prices, although the markets can certainly fluctuate. The national average went up $1.24 per pound from 2011 to 2015, reaching $4.38.

A quick aside on that price drop off in Oregon.

Like elsewhere, Oregon's overall state yield has dropped even as acreage has increased by 52 percent since 2011:

That's not the potential reason for a decrease in price per pound, but it may put a greater emphasis on the need for stronger yield. The top-five varieties grown in Oregon saw a mixed bag of results in 2015, according to YCH Hops:

- Nugget, 1,418 pounds - "exceptional"

- Cascade, 1,160 pounds - "well"

- Willamette, 792 pounds - "off"

- Centennial, 701 pounds - "big disappointment"

- Citra, 538 pounds - "average"

But back to the national view. The decision of what to plant - driven by geography and weather - should be viewed with a couple important views, according to a Washington State University study:

Lower yielding hop varieties are more expensive to produce: The popular aroma variety Citra for example will come at a premium to other varieties, since its yield is relatively lower. This also serves to illustrate the agronomic reality that in poorer crop years with lower yield, the cost per pound will increase.

Higher yielding hop varieties are less expensive to produce: Simcoe for example, may cost relatively less to produce than many varieties, since its yield is relatively higher.

As interest in growing hops increases - especially if it's to meet rising demand - the geographical choice of what and where to grow is certainly important. Not all hops are created equal when you're comparing the ideal climate of the Pacific Northwest to the Southeast, for example:

Pearson says Florida is a long way from being the new Yakima. For one thing, the yield of Florida hop plant has been small as compared to Yakima or even North Carolina. Pearson compares the harvests: "In Yakima, they traditionally harvest about eight pounds of hops per plant. In North Carolina, they get two to three. In Florida, we have been getting one pound per plant." Pearson admits that he only had room to let [University of Florida] hop plants grow to 13 feet and the plants like to stop growing around 18 feet.

All this points at a trend impacting the beer industry: the type of hop most beloved by drinkers and brewers is greatly impacting production decisions. The good: beer lovers get new, exciting flavors. The bad: there may be more of a need for variety diversity in order to be efficient in hop production.

Welcome to "Hop Week," an opportunity to look into how the production of hops impacts the beer industry, agriculture and drinkers.Bryan Roth

"Don't drink to get drunk. Drink to enjoy life." - Jack Kerouac