Not once, but twice last week I read about a presumptive sweeping movement in the beer industry: the death of the flagship brand.

First, it was Chelsie over at Stouts and Stilettos, followed by Derek at Bear Flavored. Two different takes and perspectives on the cultural rejection of the notion that breweries, as a business, might have One Beer to Rule Them All.

Is there truth to this? Maybe a little, but no more than what we could glean from when Andy Crouch wrote about this same topic in 2012 :

So in the end of an era for some pioneer brands, where consumers appear ready to fully embrace their long-developing beer brand promiscuity, the first era of the flagship is over. The ultimate result of the evolving craft beer consumer's fickle palate is the end of relations with these former beaus, only to be replaced with a new, younger and hipper string of beer relations.

Let's for a moment assume we've spent the last four years witnessing the Death of the Flagship. The most important point we should talk about is addressing the audience for which "flagship" matters.

I am the 1 percent. If you're reading this post, chances are you're the 1 percent, too. We are the ultimate minority, the beer enthusiast who thrives on promiscuity and badges on Untappd. We want to learn about new beers from new breweries to fill our portfolio of experiences, often at the risk of ignoring heritage brands or simply buying beer in "bulk," opting for single servings instead of six-packs.

There is nothing wrong with that. However, there is still 99 percent of the beer drinking public out there for which that behavior is not the norm.

Then again, this topic is wildly complicated. What we need to be asking, then, is what do the numbers show? Are flagships dying? Maybe, but not like you think.

Let's be clear: breweries across the country have beers that not only are their flagships, but will continue to be the driving force for their overall business.

- Allagash White is 80 percent of Allagash's volume.

- All Day IPA, which debuted in 2012 and accounted for 25 percent of Founders volume one year later, is more than 50 percent of volume now. The brand grew 175 percent in 2015.

- Goose Island IPA grew more than 250 percent last year and became a $19 million brand.

- Lagunitas IPA, which won't stop growing, is the top-selling IPA in the country.

- New Holland, which refocused its attention on its home Michigan market last year, saw jumps in its top performing brands Dragon's Milk (+48 percent) and Mad Hatter (+20 percent) in 2015.

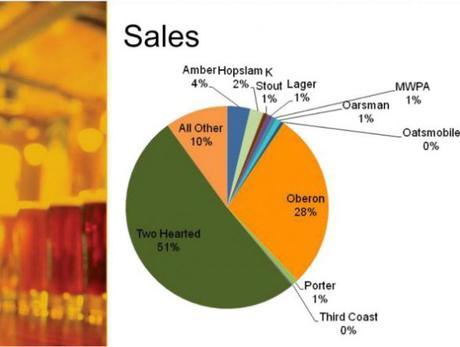

- Bell's, despite new brands like Oatsmobile and regular specialty releases, still relies on two beers for 79 percent of its volume.

I could go on.

Flagship beers, as a staple and driving force, are not going anywhere. Just ask these guys. For businesses like Allagash, highlighted below by Good Beer Hunting, one beer allows brewers to play and create the one-off Whales beer enthusiasts crave.

Many know them for their volume-leading witbier, and it's the engine that powers the vehicle. But there's also a robust, thriving, and innovative barrel and wild ale program that continues to churn out new and interesting beers. I ask Guarracino about the commitment to a program that's surely a burden to maintain, from the ingredients to the time and space required for aging, the lower yields, and just generally so much work for so little beer, relatively speaking. "One percent of sales, 100% of soul," he says.

But even as iconic brands continue to sell, that doesn't mean all is fine.

Per IRI, 15 of the top 30 craft brands showed sales decline in the first half of 2016, including names we all recognize:

- Sierra Nevada Pale Ale

- New Belgium Fat Tire

- Samuel Adams Boston Lager

Seeing these brands in this context may not come as a surprise, especially in the case of Sam Adams, which has been facing challenges to its sales and parent company Boston Beer's identity for a couple years. According to Brewbound, Boston Lager sold more than $43 million in multi-outlet (grocery, Wal Mart, drug, etc.) sales in the first half of 2014. During the same time frame in 2016, it's made $37.5 million.

Overall, six of the declining 15 brands have seen declines of 10 percent or more.

You can't address the idea of the Death of the Flagship without considering the biggest movement of the craft beer industry. While individual breweries may be more reliant on tap variety these days, that may also be due to the fact that as consumers, we've slowly moved to embrace the idea of a cultural flagship. SPOILER ALERT: it's the IPA.

Of the top-15 selling new craft brands through May 1, eight were IPA and one was a hop-forward pale ale. This comes on the heels of 2015, when nine of the 10 top-selling craft brands were IPA.

Looking at the cross section of this trend with the breweries that are leading the charge of today's top-sellers show how this need for hopped up beers impacts the companies who are suffering from declines in flagships once wildly popular. They're just replacing what people may consider their "old" flagships with new ones.

Last year, Sierra Nevada (Hop Hunter and Nooner), New Belgium (Slow Ride) and Sam Adams (Rebel Rouser and Rebel Rider) were all responsible for some of the best-selling new brands.

Through that May 1 time frame this year, Sierra Nevada (Otra Vez), New Belgium (Citradelic and Glutiny) and Sam Adams (Rebel Grapefruit, Nitro Coffee Stout, Nitro White Ale and Nitro IPA) were again among the top new brands. A mix of IPAs and current trends (gose and nitro) far from Pale Ale, Fat Tire and Boston Lager, brands that continue to lead the charge, but don't get as much attention than what's shiny and new, perhaps.

Between 2010 and 2015, New Belgium and Sam Adams had three of the six best-selling new releases, all IPA. (Sierra Nevada's Hop Hunter was 2015's best if you discount Coney Island Hard Root Beer as a flavored malt beverage and not beer) This year's top-selling brand through May 1: New Belgium's Citradelic Tangerine IPA.

Two points of information worth noting here:

- The reason these breweries are repeating are because of size (they can produce a lot) and scope (they distribute to a lot of places). So while people obviously really like these products, their excellent performance is aided by wide availability.

- The year-to-year need for innovation and offering something new highlights how necessary it can be for these businesses to remain relevant at a time when variety and finding new experiences are at a premium.

"It's a crowded marketplace," Alarmist Brewing's Gary Gulley said on a recent Good Beer Hunting podcast. "You need to evolve who you are and what you're doing."

Ten minutes later in the conversation, GBH host Michael Kiser added to the thought.

"If I'm a big brewery and I need to keep things moving, which is what larger companies have to do," he said, "coming out with something that's on trend, at a time when people want it, that's going to soak up in the market, is the perfect place to be for larger brewery."

All this emphasizes the reality of how and why the idea of a flagship may be waning. "New" is necessary and that means changes for what's most popular on a yearly basis. Look at how the top-selling styles have adjusted in recent years with extra emphasis on this year's rankings, as reported by IRI:

In 2016, IPA is set to have nearly a * third* of craft dollar sales in supermarkets and similar stores, followed by two styles that are defined by rotational flavors.

One avenue from which to view the Death of Flagship is the Rise of Variety, something I've written about before and more recently pointed out in this post about Millennials, beer's most pivotal demographic.

In IRI's tracking of supermarket beer sales through May 1, the company noted several year-to-year gains in single packaged bottles. Twenty-two ounce bombers are up 6.8 percent, single 11 or 12-ounce bottles are up 22 percent and single 16 to 17 ounce bottles are up 67.6 percent in 2016. But also think about the bottle shops you visit, where setting out individual 12-ounce bottles or cans is the norm and grocery stores which have made the "mix a six" selection common.

Also, consider the buying behavior of Millennial beer drinkers:

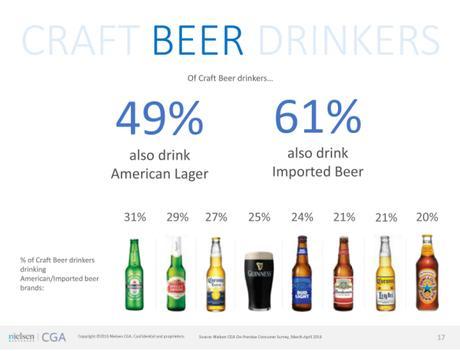

And the fact craft beer drinkers consume a variety of brands:

According to Nielsen, the average number of alcohol drink brands in a craft beer drinker's portfolio - across all kinds of alcohol - is 24, almost double the national average of 15. Interests range widely and for those who seek out unique flavor experiences, it only makes sense that these drinkers would be promiscuous in their selection of booze.

Is there a definitive answer to this question? Are flagships dying? Or is it just our mentality toward them?

Probably a little of both.

Even as sales decline for classic brands, former flagships are just being replaced by *new* flagships or rotational ones. The variety that we seek and crave is matched by the innovation and creativity of the industry's brewers, after all. Flagships act as a point of reference for a business. But when a diverse collection of brands is necessary and styles become more important, it makes sense all this would happen.

Or maybe it's simply because we have thousands of options in front of us when we walk down the beer aisle and brand switching happens because it can.

I don't think there's a debate to be had about whether we need to write a eulogy for the idea of flagship beers - there's too much proof that they not only exist but are pivotal for many breweries - but the psychology and expectation around such a thing has certainly changed. Our old flagships - the beers we personally choose to enjoy - are just becoming new ones. Life, death, rebirth.

(Note: Want to learn more about problems flagship beers face? Read my story "Life and Death of a Beer" in the latest issue of All About Beer magazine.)Bryan Roth

"Don't drink to get drunk. Drink to enjoy life." - Jack Kerouac