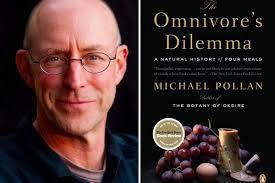

Michael Pollan is a food thinker and writer. Not a restaurant reviewer; he looks at the big picture of what we eat in The Omnivore’s Dilemma. (Carnivores eat meat; herbivores eat plants; omnivores eat both.)

Michael Pollan is a food thinker and writer. Not a restaurant reviewer; he looks at the big picture of what we eat in The Omnivore’s Dilemma. (Carnivores eat meat; herbivores eat plants; omnivores eat both.)

The book is a smorgasbord of investigative reporting, memoir, analysis, and argument. Pollan does have a strong point of view; cynics, pessimists and misanthropes will find much fodder here. But Pollan is no fanatical purist ideologue. We saw him on a TV piece summing up with this core advice: “Eat real food, not too much, mostly plants.” Seems pretty reasonable.

He’s a lovely writer. Here’s a sample, concluding the first of the book’s three parts, talking (perhaps inevitably) about McDonald’s:

I might disagree with his evaluation, but man, this guy can write.

Pollan sees food industry economic logic driving us toward a kind of craziness. When the government started intervening in farm produce markets, the aim was to support prices by preventing overproduction. Remember farmers paid not to grow stuff? But in the 1970s that reversed, with the system now incentivizing ever higher yields, aided by technological advances. The resulting glut, in a free market, should drive prices down, signaling producers to cut back. However, if farm prices fall below a certain floor, the feds give farmers checks to make up the difference. Thus their incentive now is to just grow as much as possible, no matter what.

Meantime it’s a challenge to market all that corn. That’s why so much goes to animal feed. The industry has also cajoled the government to require using some in gasoline (ethanol), which actually makes neither economic, operational, nor environmental sense. But it does eat up surplus corn.

Part of the marketing challenge is that while for most consumer goods you can always (theoretically at least) get people to buy more, there’s a limit to how much a person can eat. So with U.S. population growth only around 1%, it’s hard for the food industry to grow profits by more than that measly percentage.

The abundance and consequent (governmentally subsidized) cheapness of corn figures large here. It goes into a lot of foods like soft drinks (yes, full of corn too!) that also attract us by their sweetness. Unsurprisingly, lower income consumers in particular go for such tasty fare that’s also cheap — buying what provides the most calories per budgetary dollar.

But the main driver of obesity is simple biology. We evolved in a world of food scarcity, hence with a propensity to load up when we could, against lean times sure to come. Thus programmed to especially crave calorie-rich sweet stuff. But it being no longer scarce, indeed ubiquitous, no wonder many get fat.

However, Pollan chronicles his stint at one actual farm that might be called beyond organic. This read to me like one of those old-time utopia novels. And that farm is actually extremely efficient. But its model doesn’t seem scalable to the industrial level needed to feed us all. Also, it’s extremely labor- and brain-intensive. Few farmers today are up for that.

The farmer profiled there opined that government regulation is the single biggest impediment to spreading his approach. It gives USDA inspectors conniptions. Pollan shows how the whole government regulatory recipe is geared to bigness.

The book also delves deeply into the ethics of eating animals, a fraught issue. I will address that separately soon.

* Well, there are some, like no antibiotics. Today’s organic farming is a sort of kludge — Pollan likens it to trying to practice industrial agriculture with one hand tied behind your back.