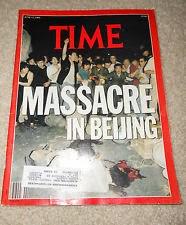

In the summer of 1989, I was living in Seoul, South Korea--on Yeouido (여의도) island, in fact, just a few miles from the 63 Building. (I strongly doubt any foreign missionaries could afford apartments there today.) The heavy rains of the summer had come early that year, or at least that was my memory. I was just about halfway through the 22 months I was spending in the country as a church missionary, and by that time I probably had learned about as much Korean as I ever did master, unfortunately. It was enough to be able to follow in a very general way the information I caught on the occasional television news program which I'd watch while eating at a restaurant or visiting a friend's apartment, but I still kept an eye out for English-language newspapers and magazines, and would grab a copy whenever I could. And then came a day in June, perhaps a week or so after the event in question, when I managed to find this copy of Time.

In the summer of 1989, I was living in Seoul, South Korea--on Yeouido (여의도) island, in fact, just a few miles from the 63 Building. (I strongly doubt any foreign missionaries could afford apartments there today.) The heavy rains of the summer had come early that year, or at least that was my memory. I was just about halfway through the 22 months I was spending in the country as a church missionary, and by that time I probably had learned about as much Korean as I ever did master, unfortunately. It was enough to be able to follow in a very general way the information I caught on the occasional television news program which I'd watch while eating at a restaurant or visiting a friend's apartment, but I still kept an eye out for English-language newspapers and magazines, and would grab a copy whenever I could. And then came a day in June, perhaps a week or so after the event in question, when I managed to find this copy of Time.The June 4th Tiananmen Square Massacre--the violent crushing, via the armed force of the People's Liberation Army, of the massive, disorganized, dizzying popular demonstrations which had been taking place in Beijing's central Tiananmen Square since April--had managed to pass me by entirely. I later learned that just about everyone in Seoul had been talking about the tragedy, and I saw more than enough news coverage of it through various Western sources. But on the South Korean news programs, there was nothing--the order had come down from the government not to discuss the massacre, as it was feared that it would remind people too much of the Gwangju Uprising, when hundreds of Koreans were slaughtered by the South Korean army when they took control of the city of Gwangju during a period of martial law. (South Korea in 1989 was technically on its way to becoming a genuinely free, mostly liberal, multi-party democracy, but its president at the time, Roh Tae-woo (노태우) had still been hand-picked by a former military dictator, Chun Doo-hwan (전두환), who himself had ordered the Gwangju slaughter in 1980, and many political and social restrictions were still in place--all of which were unmentioned in the media and constantly protested in the streets, leading one local American I knew to refer to South Korea, riffing on one of the nation's traditional names, as "the land of morning calm and evening riot.") So unknown number of violent deaths--probably numbering in the thousands, though no official numbers have ever been released--out of the more than a million Chinese students, Beijing locals, and others who participated in those demonstrations went essentially, officially, undocumented in the country right next door.

When I returned to America and went back to BYU in 1990, I wanted to understand the culture and people that I'd been sent to preach to, and I began to study Asian politics and philosophy. While I never became anything like an authority on Chinese politics, in those years while I was completing my undergraduate degree and then getting my MA, it was impossible to go to a conference, to gather together with other students, or to meet with faculty in my area, and not have the events of the year before, or of two or three or four years before, come up at some point or another. We were all former East Asian church missionaries, or people who'd spent time doing business or teaching English in Hong Kong, Tokyo, Taipei, and elsewhere, or both--and all of us had, at the time, desperately scavenged for news coming out of the PRC. (This was pre-internet, folks.) As students in the years to come, we went to hear from dissidents and troublemakers that our professors knew and managed to bring to campus, as well as apologists for the regime (I can remember one time when, in a gathering at a small campus theater, some representative of PRC government, perhaps someone from the consulate nearest to Utah, answered questions about the causes behind the demonstrations, leading one Chinese student at BYU to bravely shout out "You are a liar!"--after which all his friends quickly hustled him out of the theater, before he could be identified, have his student visa stripped from him, and suffer the consequences). Nothing seemed more important to me, back then, then contributing to the debate about how to help bring democracy to China, and punishing those in power. The mostly forgotten argument over giving China special trading privileges with the U.S. seemed massively important to me then. When it looked like China was going to be successful in landing its bid for the 200 Summer Olympics, it seemed like a terrible scandal. And so forth, and so on.

When I returned to America and went back to BYU in 1990, I wanted to understand the culture and people that I'd been sent to preach to, and I began to study Asian politics and philosophy. While I never became anything like an authority on Chinese politics, in those years while I was completing my undergraduate degree and then getting my MA, it was impossible to go to a conference, to gather together with other students, or to meet with faculty in my area, and not have the events of the year before, or of two or three or four years before, come up at some point or another. We were all former East Asian church missionaries, or people who'd spent time doing business or teaching English in Hong Kong, Tokyo, Taipei, and elsewhere, or both--and all of us had, at the time, desperately scavenged for news coming out of the PRC. (This was pre-internet, folks.) As students in the years to come, we went to hear from dissidents and troublemakers that our professors knew and managed to bring to campus, as well as apologists for the regime (I can remember one time when, in a gathering at a small campus theater, some representative of PRC government, perhaps someone from the consulate nearest to Utah, answered questions about the causes behind the demonstrations, leading one Chinese student at BYU to bravely shout out "You are a liar!"--after which all his friends quickly hustled him out of the theater, before he could be identified, have his student visa stripped from him, and suffer the consequences). Nothing seemed more important to me, back then, then contributing to the debate about how to help bring democracy to China, and punishing those in power. The mostly forgotten argument over giving China special trading privileges with the U.S. seemed massively important to me then. When it looked like China was going to be successful in landing its bid for the 200 Summer Olympics, it seemed like a terrible scandal. And so forth, and so on.Well, they eventually did get their Olympics in 2008--and 25 years on, the word from China is that most young people are pretty unfamiliar with the protests and the enormous bravery shown by thousands of people who engaged in hunger strikes, marches, and life-threatening civil disobedience, so as to be heard by their government. And I'm still no expert about China--indeed, given the huge changes globalization has wrought over the past quarter-century, I'd have to say I know less about China's people, culture, language, aspirations, and politics today than I did back then. (The fact that I ended up doing almost nothing with East Asia during my graduate school years--this article is about the only evidence of the passions that I carried with me from my BYU years--may have contributed to that as well, of course.) I may have a chance to visit China this coming year, speaking at a conference in Nanjing; it'd be my first visit back to East Asia since my Hong Kong trip four years ago, and dearly hope it works out. No fears about visiting China? None at all. Whatever the many good and important things that we hoped for and wrote about back then which haven't worked out, so many other unexpected good things, good things that many students and friends of mine who have visited and lived in China over the past 25 years have testified of, actually have worked out. China is, in so many ways, clearly a better place to live today than it was a generation ago. This hasn't made China into a democracy, by any means, but the sort of state violence which it wielded in downtown Beijing back in 1989 is probably pretty much inconceivable today, by the Chinese themselves and the millions who do business with them. And that is, most certainly, the best good thing of all.