Last Christmas, a close friend turned to me and plaintively, frustratedly asked "What is the point of art?"

Our table had been discussing the increasing reports about creative exploitation and unfair compensation in film and television. The cloudy night had cast a gloomy mood over us despite the holiday cheer, our low spirits punctuated by our shared inability to come up with a convincing answer. I left dinner discontent, her words spinning in my mind sans resolution.

But a little over half a year later, I found one at FlameCon. Amidst the brilliant colors, cosplays and ebullient chatter occasionally interrupted by the loud enthusiasm of people finally meeting a favorite creator or one whose work really got them in their hyper-specific sweet spot for sapphic selkie girls or messy, morally ambiguous alien anthropologists, I saw how the shared language of fandom, of queer art theory, of the internet-enabled intersection between the two, was all bringing people together.

Even as the United States sees massive rollbacks to basic LGBTQ+ rights and literary freedom, queer stories are more in demand than ever-I walk through the YA section of my local library regularly, filled with the bittersweet delight of seeing an ever-growing number of explicitly sapphic books on the shelves. We didn't even have Pride Month displays when I was a kid, and I only stumbled upon Malinda Lo's Ashafter a straight crush told me it was "weird". But now, there are organized movements vocally, visually defending the right to read graphic novels like Fun Home, Moonstruck, Gender Queer, and This One Summer. I couldn't even say the word gay until I started college, let alone imagine going to a fan convention that celebrates both the biggest out names on the Big 2 roster and the smallest self-published zine creators with abundantly gay abandon.

With its volunteer-run programming and many, many self-published book and zine sellers, FlameCon offers attendees a little oasis of creator-controlled and riotously boundless self-expression. It's a chance for people to network, take note of rising talent, and celebrate the stories that mean the most to them. Usually by completely transforming them. Alternate New Yorks, Superbat kisses, and bloodstained femgaze fighters are just a taste of what's on display. There was also, as always, a spectacular array of anime merch that eluded my not insignificant knowledge of the genre.

I was pleased to note, however, that recent internet trends had sparked new fervor for the Trigun franchise. Merilly fanfiction has long been my safe harbor, the sort of tender, deeply felt sapphic relationship that doesn't have the heightened emotional fraughtness of Harlivy or the raw-nerve traumatic underpinnings of Korrasami, Bubbline, Hollstein, or most other favorites. It warms my heart to watch others find such harbors for themselves, and then populate them with all manner of original works-like the grounded and sweet " Girls Like You " webcomic, or the unhinged goldmine that is SuperCorp fanfiction. Seriously, the ingenuity and independence of queer creators never ceases to surprise.

Which brings me to the point of it all. Art is our oldest and deepest form of communication, of connection. Whether that takes the form of riotous cheering after a speaker drops a deep-cut reference, or the audience's knowing smiles when every panelist mentions a history of fanfic or fanart, there is a sense of community to be found through sharing stories. In finding the words to describe our experiences-finally being able to articulate who we are and knowing how we got here-we learn to understand others. Maybe not as well as ourselves, but there is something beautiful about the way art can offer us reflections that ring truer than anything we see in the backlit silhouettes on department store windows.

To paraphrase what Maia Kobabe said in the excellent short documentary "No Straight Lines", sometimes we don't recognize ourselves in photographs, in silver-lined mirrors whose reflections don't offer much in the way of silver linings. But in art, we can draw/write/portray ourselves however we want. However we feel, need, believe, desire, live, and wish. And that can open up possibilities we couldn't perceive before we took a pen in hand.

Art teaches us that we are not alone, and that shared passions can lie in unexpected people. Watching the milling crowds trading artwork and recommendations, I couldn't help but smile. Because all those little communications open windows into others' lives, offering languages both visual and textual for sharing and validating our experiences, and for making meaning of them. Those conversations show that people care, for better or worse, what others have to say about the world we live in. That they are still looking for stories to share, to adapt, to define the future they are building for themselves and others.

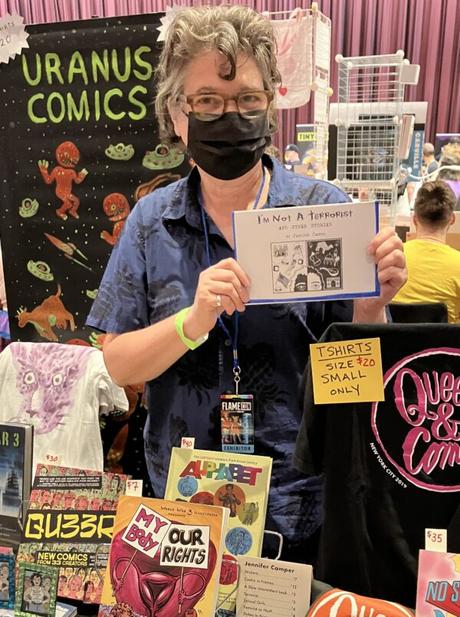

"If I am writing about a culture different than my own, I have multiple people from that background read my work, and I'm really sad that we use this term 'sensitivity readers'. What I call it is fact checking. You know, if I put in a tractor mechanic, I want a tractor mechanic to read this and make sure it looks right." ~ Jennifer Camper (she/her)

On another panel, Charlie Jane Anders and other spec fic writers recommended Nisi Shawl and Cynthia Ward's Writing the Other for all those aspiring writers wondering how to write diversity into their characters. Meanwhile, Camper continued with recommendations to at least start by reading works by people from the communities or identities you wish to represent, in order to see how they choose to represent themselves-and why.

Jennifer Camper and some of her contributions to queer comics history. This woman is an icon. Find a copy of "No Straight Lines" at your local (university?) library for a glimpse at the truly rich history of this slowly growing slice of self-expression.

Speaking of how people choose to represent themselves, I planned to write something poignant and touching about the panel on queer vampires, but I was so swept away by the energy and cheering and pure delight of being immersed in all my favorite aspects of my favorite niche interests (queer history, monstrousness in art, lesbian vampires, B-movie metaphors, etc.) that I came out of it with a sense of complete restorative well being...and that's it. It's amazing how wonderful those moments of total acceptance feel after a lifetime of self-censorship, how powerful, affirming and centering it is to experience such enthusiastic communal understanding.

"I like working with Claudia Aguierre because...she's a queer, lesbian, Mexican woman. And so I can write stuff in there that's queer and Mexican...Like, there is a shorthand that I think comes with working with other queer people and it sometimes feels a little more like freedom. You're like, "Okay, I don't have to explain.""

"I always bring all the different little pride stickers and lay them out. And then I get these kids who walk up and like, that's awesome. These feral teens, it's like "I see you, I was you, I get it" and I think that's the key thing. We talk about things like gaydar-we do have a way of finding each other out in the world, which I think is really cool."

This year, I bought a Vashwood print for someone close to me, who abruptly came out over the phone when I casually mentioned that I couldn't talk because I was at "a gay comic-con".

This little anecdote is a testament to how even the most innocuous complaints about Ino and Hinata being a better endgame, or jokes about cosplaying "all the black-haired bisexuals" may come across as cringy to some, but show others that you are someone they can turn to. Someone they can trust. Someone who will hike up and down an artist's alley to find them a slash print that is not gay enough to freak out their parents, but soft enough to offer hope for a loving future.

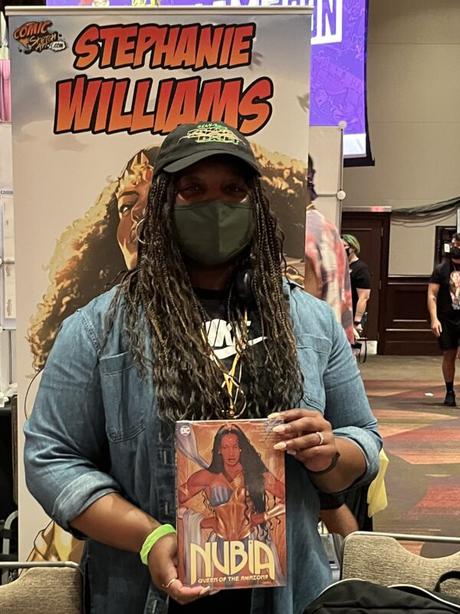

Stephanie Brown, writer for the series. I really appreciated the care Brown gave the characters' backstories, as well as all the amazing artists who worked on the interiors. The cover gallery is gorgeous, too. It definitely benefits from a certain familiarity with DC comics lore, but it is a solid starting point for someone looking to dip their toes into the vast ocean of superhero comics.Symbols are powerful things, and as Barthes' would likely agree, our modern mythmakers aren't Homer, Ovid or Aesop (though their narrative structures and values continue to hold outsize influence). Our modern Hesiods include people like Stephanie Brown, Marjorie Liu, Kieron Gillen, and Natasha Alterici, whose art was one of the promotional prints for " Sharp Wit & The Company of Woman ". I love her art, and was an excellent interpretation of Norse mythology and regional history.

While these creators may not be quite as canonized as the bust inspirations that came before, their contributions to queer imaginings are powerful refusals to soften edges, to keep room for complexity, fallibility and the driving forces of desire that echo through the most resonant legends. Their characters, in all their other-landishness, play with and subvert the abstraction of archetype to reveal far more boundary-blurring realities that hew closer to what it means to be human in an ever-changing and often destabilizing world. There are quiet reckonings on these pages, as world-shakers and mountain-movers make way for smaller-scale consequences that weigh no less heavy on their makers' shoulders, or private pleasures that refuse to be generic or prescriptive, that insist on specificity and subjectivity for the characters even as their creators' wink at the inspirations.

"I think things have really changed. And I hope they keep changing. And I hope that the more queer stories that we have out there, the more doors are open...now that we have more queer people writing queer characters...we don't all have to be packaged a certain way to be respectable, to be commodified. So yeah, we're just writing people, and people are messy and weird and delightful and awful, and it's great." ~ Alyssa Wong (they/them)

"Art requires truth" is one of the last lines from Mari Walker's taut, disquieting 2021 character study See You Then. While I wasn't able to attend the last panel on Intimacy in Comics, it was the line that came to mind while I was waiting for the train back home. In this era of microcurated realities and fandom mentalities that have spilled beyond con floors and discussion boards into arenas of greater effect, connection and the truth it demands of us take on new significance and meaning. Art takes on that meaning, that significance, that urgency. It becomes that hand reaching out through the obfuscation, opacity, fear and loathing; a reminder that there is so much more out in the world, and in history, than any of us can ever begin to experience. Can ever dream of imagining.

So make art, make love and tell the stories only you can.

NOTE: All the quotes are from published authors, artists, and editors. Check out their work!