There is no bigger question. After all, what is the point of life? I’ve authored a book titled Life, Liberty, and Happiness, arguing that ultimately the only thing in the cosmos that matters is the feelings of beings capable of feelings. Nothing can matter unless it matters to someone.

There is no bigger question. After all, what is the point of life? I’ve authored a book titled Life, Liberty, and Happiness, arguing that ultimately the only thing in the cosmos that matters is the feelings of beings capable of feelings. Nothing can matter unless it matters to someone.

Weighing in on this is Yuval Noah Harari’s 2017 book, Homo Deus – A Brief History of Tomorrow. He posits that human happiness will increasingly occupy our attention. It didn’t always. “Pursuit of happiness” in the Declaration of Independence was a revolutionary idea when most people were too preoccupied with just surviving to think about whether they were happy.

Epicurus

Yet unpacking the concept of happiness has always vexed philosophers. Epicurus (341-270 BC) fingered the centrality of pleasure versus pain, but what he advocated wasn’t hedonism; his idea of pleasure was almost Spartan. Harari meantime says all pleasures really resolve down to just internal bodily sensations, which he denigrates as mere “vibrations” (evoking the “good vibes” of the ’60s). And when he says all, he means all. Applying not just to sensations like orgasms but to pleasures we might call mental or psychic. If you feel good about a job promotion, Harari says what’s really happening is a set of bodily sensations. That’s all.

And the problem, Harari insists, is that such sensations are always fleeting. Hardly is one experienced before it’s gone. So if your life is about happiness qua sensations, you’re condemned to forever chasing them without being able to hold onto them. A recipe for frustration and thus, indeed, unhappiness.

This perspective is basically Buddhist, as Harari acknowledges. Buddhism teaches that the quest for pleasure — to fulfill our desires — is actually the root of suffering. We can stop suffering only by letting go of the desires.

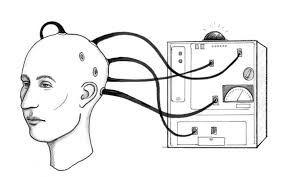

Admittedly, emotions do entail physical sensations. I remember one episode of real bodily pain after an argument with a girlfriend; and I feel tingles hearing the national anthem. But it’s still wrong to assert that such bodily sensations are all there is. Clearly, what the mind thinks in such episodes is the main event.

I often do reflect on Harari’s point about the evanescence of sensations. Considering myself a sensualist who does deeply savor pleasures, I am acutely conscious of their impermanence. When eating a cookie I try to do it mindfully, to experience it fully while I can. Trying to grasp hold of its reality. But what it really means to taste a cookie, as a mind/brain phenomenon, is extremely hard to wrap one’s mind/brain around; it seems to disappear in the effort. And meantime, given the fleetingness of sensations themselves, I find that anticipation and recollection are more important. Again, it’s complicated.

Harari weirdly omits any discussion of the ancient Greek concept of eudaimonia. It casts happiness not as rooted in transitory sensations but rather in a “life well lived.” What does that mean? Clearly not a life full of caviar and sex but, for example, a life of nourishing connections to others, family love, civic engagement, worthwhile accomplishment, intellectual growth, and so forth. It is the antithesis of focusing just on sensations, looking instead upon one’s life as a whole. That provides a baseline sense of well-being that supersedes not just the momentary impacts of “vibrations” but even of life’s more consequential vicissitudes.

Thus — although as noted all sensations are ultimately mental constructs — eudaimonia (in contrast to Harari’s fleeting “vibrations”) is a mental construct with continuity over time.

Buddhist this is not. At one time my greatest desire was to find a partner; relinquishing that desire would not have brought me to nirvana. Instead I pursued it and succeeded. My marriage does entail some momentary (ahem) bodily sensations — but its impact on my overall mental state continues over time, ever present in my consciousness. A foundation of my eudaimonia.