We have a pretty good idea of the characteristics that support very high individual performance in a variety of fields, from jazz to track to physics to business. An earlier post discussed some of the different combinations of features that characterize leaders in several different professions (link). And it isn’t difficult to sketch out qualities of personality, character, and style that make for a great teacher, researcher, entrepreneur, a great soccer player, or an exceptional police investigator. So we might imagine that a high-performing organization is one that has succeeded in assembling a group of high-performing individuals. But this is plainly untrue — witness the New York Yankees during much of the 2000s, the dot-com company WebVan during the late 1990s, and the XYZ Orchestra today. (Here is a thoughtful Mellon Foundation study of quality factors in symphony orchestras; link.) In each case the organization consisted of high-performing stars in their various disciplines, but somehow the ensemble performed poorly. The lesson from these examples is an obvious one: the performance of an organization is more than the sum of the abilities of its component members.

In fact, it seems apparent that organizational performance, like physical health, is a function of a number of separate parameters:

- clarity about mission

- appropriateness of internal functional specialization

- quality of internal communication and collaboration across units and individuals

- quality and intensity of individuals

- quality of internal motivation

- quality of leadership

So what else goes into determining great organizational performance besides the quality of the individuals who make it up? A few things are obvious. Of course it is true that having individual participants who have the right kinds of talents is crucial. A technology company needs excellent engineers and designers. But it also needs highly talented marketing professionals, financial experts, and strategic planners. And it needs these talented specialists in a number of critical areas. Why did Xerox PARC fail in spite of the excellence of its scientists and engineers, and the innovativeness of the products that they created? Because the organization lacked the ability — and the individuals — to turn those ideas and innovations into products that the public wanted to buy. (Here is Malcolm Gladwell's take on Xerox PARC in the New Yorker; link.)

A key aspect of the problem of designing and tuning an organization’s features to ensure high performance is being able to determine with precision what the mission of the organization is. What is the organization fundamentally established to bring about? If the Red Cross is an organization that is intended to deliver resources and assistance to communities that have suffered extensive disasters, that implies one set of functional needs to be satisfied by divisions and specialists within the organization. If it is primarily a fund-raising and marketing organization aimed at raising public awareness and generating large amounts of public donations to be used for disaster relief, that implies a different set of internal specialists. So being clear about the overall mission of the organization is crucial for the designers, so they can skillfully design a set of divisions, specialists, and work processes that can work together effectively to carry out the tasks necessary to succeed in achieving the mission.

This point highlights the fact that an organization needs to have a functional structure in which the activities of individuals or departments carry out specialized tasks. These sub-units depend upon the high-level work of other departments or individuals, and the functional structure of the organization can be more or less appropriate to the task. The organization succeeds to the extent that its component parts succeed in identifying the needs and opportunities facing the organization and in carrying out their roles in responding to those needs and opportunities. Poor performance in one department can have the effect of ruining the overall success of the organization to carry out its mission — even if other departments are highly successful in carrying out their tasks. Charles Perrow highlights this kind of organizational deficiency in Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies.

Here is another important variable in bringing about organizational effectiveness: the procedures within the organization that are designed to encourage high-quality effort and results on the parts of the individuals who occupy roles throughout the organization. One line of response to this issue flows through a system of supervision and assessment. This approach emphasizes measurement of performance and positive and negative incentives to motivate satisfactory performance. Supervisors are tasked to ensure that employees are exerting themselves and that their work product is of satisfactory quality.

But a different response proceeds through a theory of internal motivation. Leaders and supervisors encourage high-quality effort and achievement by expressing the valuable goals that the organization is pursuing and by offering the reward of participation in effective work that one cares about to employees. This positive motivational feature is strengthened if the organization visibly maintains its commitment to treat its employees fairly and decently. If an employee is proud to work for Ben and Jerry’s, he or she is strongly motivated to make the best contribution possible to the work of the company. In a nutshell this is the theory that underlies the very interesting literature of positive organizational scholarship (Kim Cameron and Gretchen Spreitzer, The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship).

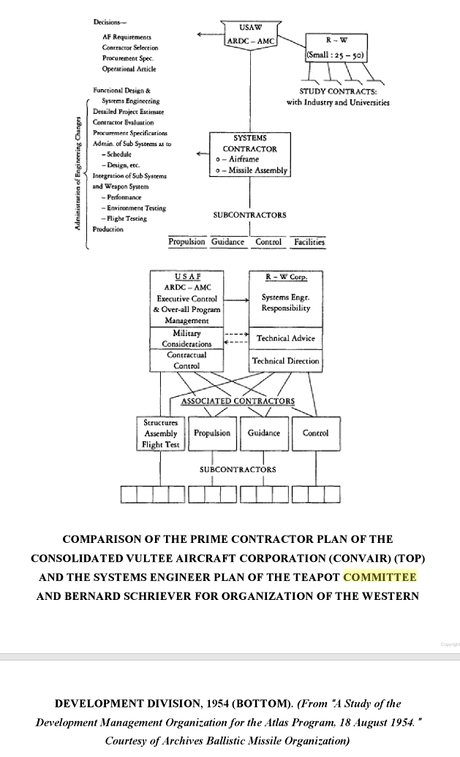

A fifth facet of organizational performance plainly has to do with internal communication, coordination, and collaboration. The eventual success or failure of an organizational initiative will depend on the activities of individuals and units spread out throughout the organization. The work of various of those units can be made more effective or less effective by the ease and seriousness with which they are able to communicate with each other. Suppose a car company is designing a new model. Many units will be involved in bringing the design to fruition. If the body designers, the power train designers, and the manufacturing engineers haven’t talked to each other, there is a likelihood that solutions chosen by one set of specialists will create major problems for the other specialists. (The Saab 900 of the late 1970s was a beautiful and high-performing vehicle; but because the design process had not taken into account the need for convenient servicing, it was necessary to remove the engine to carry out some common kinds of repair.) Thomas Hughes provides an excellent analysis of the organizational deficiencies of the design process used in the United States military aerospace sector in the 1950s and 1960s in Rescuing Prometheus: Four Monumental Projects That Changed the Modern World. Here is his comparison of good and bad organizational forms:

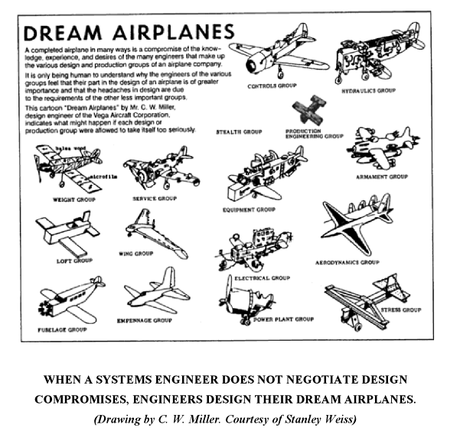

The top diagram is entirely hierarchical, with decision-makers at the top deciding the flow of work below and essentially no communication across sub-units. The bottom diagram, by contrast, involves a great deal of internal communication, allowing for adjustment of design and timing decisions so that the eventual plan has the greatest likelihood for success. The latter permits the implementation of systems engineering rather than component engineering. Here is Hughes's depiction of what happens when an organization lacks good internal communication and coordination:

What this implies is that improving organizational performance is a bit like tuning a piano: we need to continually adjust the factors (motivation, collaboration, mission, leadership, specialization) in such a way as to create a joint system of activity that succeeds at a high level in creating the desired results.

What this implies is that improving organizational performance is a bit like tuning a piano: we need to continually adjust the factors (motivation, collaboration, mission, leadership, specialization) in such a way as to create a joint system of activity that succeeds at a high level in creating the desired results.(I used images of musical ensembles to open this topic. But how good is the analogy? Actually, it is not a particularly good analogy. The issue of the quality of the players is obviously relevant, and quality of leadership has an exact parallel in the symphony orchestra. But the task of giving an excellent performance of Dvorak's ninth symphony is much simpler than that of bringing about a successful intervention by FEMA in response to a hurricane. There is a score for the musicians; there is a central conductor who keeps them in step with each other; and most crucially, there is no uncertainty about what to do once the third movement is finished; the musicians turn the page and move on to the fourth movement. Perhaps the jazz ensemble pictured above is a slightly better metaphor for a complex organization in that it leaves room for improvisation by the players. But even here, the activity is orders of magnitude simpler and easier to coordinate than a large organization whose actions take place over months or years, dispersed over thousands of miles and multiple sites of activity. So organizational effectiveness is a more complex process than musical coordination and performance.)

(I emphasize here the importance of collaboration as a variable in organizational effectiveness. This suggests examples drawn from team activities like soccer or a research laboratory. But some experts doubt the idea that teams are always superior to more hierarchical structures. Here is J. Richard Hackman on the positives and negatives of teams (link).)