This is a “philosophy contest” advertised by the “World Roundtable Association of Amateur and Professional Philosophers.”*

It solicits a list of humanity’s top 20 problems, and their solutions. While our top few problems might seem pretty obvious — cue the “four horsemen” — solutions are not. Especially real feasible solutions that could overcome many people’s self-interest and a host of other pragmatic obstacles. As opposed to pipe dreams.

My take on our biggest problem may be surprising. We’ll get to that in due course.

In 2009, I authored The Case for Rational Optimism, seeing a lot of positive trends. It would be far harder to write today, much having gone sour. For example, democracy was proliferating globally then; now it’s receding, with authoritarianism ascendant. Indeed, worldwide surveys show declining belief in democracy, with increasing allure of “strong man” rule. And whereas we’d seemed to put wars among major powers behind us, Russia’s Ukraine aggression has smashed that pretty picture, while China seems hell-bent on attacking Taiwan. In America, a non-white president appeared to herald improving race relations. But that provoked a fierce backlash. And who could imagine a presidential election might be won by a man who’d tried to overthrow the previous one?

Then there’s inequality. World poverty has, in the big picture, plummeted over recent decades — though lately that gain has stalled if not reversed, while the rich are getting much richer.

And, back in 2009, climate change looked more manageable than it does today. This of course tops many lists of our biggest challenges.

But perhaps there’s a perspective that can tie together all our disparate problems — and even show a path toward remediation.

A key theme in my Rational Optimism book was our deployment of rationality and knowledge to attack problems and improve quality of life. But there’s never a free lunch; always a price to pay; yet on the whole, again through use of reason, we’ve generally managed to still come out ahead. Some scolds fault humankind for “raping the planet,” but without making use of its resources we’d still be living in caves and wearing animal skins.

Climate change and its harms constitute a huge price that we’re now paying for our progress. Yet it remains possible to cope, as we always have, by doubling down on use of reason, knowledge, science, and technology.

Indeed, that’s the way to tackle all our problems. Using our brains, thinking better. That prescription is not just pablum. The Ukraine invasion was a product of messed-up thinking. In fact, Russia’s having the regime it does, in the first place, was down to poor thinking. As is the trap of authoritarianism everywhere. And America’s Trump cult. And so forth.

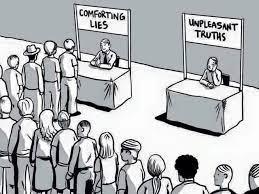

We have the capability to do better. A key element is simply knowing truth from falsehood. You can’t deal effectively with any challenge without having the facts straight. So many of our problems are worsened, and made harder to address, by that very basic issue. Certainly, for example, America’s Covid tragedy was heightened by so many people unable to distinguish reality from lies.

Confirmation bias is a major factor here. It’s the proclivity to embrace information bolstering a pre-existing belief or preference, while shunning anything contrary. A powerful aspect of human psychology, hard to avoid. In fact, smarter people are better at confabulating rationales to support their confirmation bias.

A huge confirmation bias machine in human life is religion. We are psychologically wired for that too, it pushes a lot of our buttons. And it really makes us want to believe certain things. Mark Twain said “faith is believing what you know ain’t so.”

Some see religion and science as just alternative belief systems, equally valid. However, in religion one believes basically because one wants to. Whereas science is not a “belief system” at all, but rather a systematic method for ascertaining verifiable facts about reality.

Religion is, indeed, a “gateway drug” for wrong belief and eschewing reason. It scrambles the brain’s ability to think rationally and objectively. If you can believe the world is controlled by a man in the sky, who you’ll meet after death, it’s but a small step to believing Trump election lies — or a Putin saying he’s fighting Ukrainian Nazis — or that the answer for gun violence is more guns, or that climate change is a hoax, or other conspiracy theories.

It’s no coincidence that America’s strongest religious believers, and those who swallow those Trump lies, and reject climate change and Covid vaccination, etc., are largely the same people.

Some nevertheless imagine religion is, on balance, a good thing, the indispensable foundation for morality. Surely that notion has been exploded by rampant Catholic clergy sex crimes, the atrocities of Iran’s theocracy, and so much more. In fact, we don’t get morality from religion, religion gets it from us — being coded into our genes, and originating in our use of reason. Religion actually confuses moral thinking; especially when instilling feelings of righteousness and demonizing people not on the same page. Hence religion has always played an outsized role in our whole blood-drenched history of conflict, and man’s inhumanity to man. While, in stark contrast, advanced nations, especially in Europe, notably the Scandinavians and Nordics — where religious belief has mostly disappeared — are the nicest, most orderly, peaceable, humane, and ethically advanced places on Earth.

How so? Because their brains are not scrambled by religion and superstition. Freeing them to think better, more rationally, more able to tell reality from fantasy. Better equipping them to tackle every sort of problem.

And it was better thinking in the first place that enabled them to overcome the religion that was holding them back. Better thinking begets better thinking.

So we see it’s religion that tops the list of the world’s problems. It’s the greatest obstacle to human progress, in so many spheres. And freeing ourselves from religion is the potential solution to all problems — or, at least, our best hope to find and deploy real solutions.

It won’t be easy. Religion is of course a very tenacious fixture of human culture. And it fights (especially in Muslim realms, where dissent can get you killed). But whereas in past epochs, when alternatives to religious belief seemed practically nonexistent, now its mystique is broken, and a better, more persuasive path has become more visible to ever more people. Proponents of humanism must continue making the case for it, proactive and forcefully.

Those mentioned Europeans who have largely ditched religious superstition point the way, proving this is a realistic hope. Not a pipe dream.

* Closing December 1 — send entries to [email protected]