One recent poll I saw was asking respondents if the United States was going to have a recession. It's a bit late to be asking that. We are already in a recession, and it's a serious one. Considering the huge numbers of unemployment claims and closed businesses, it's going to make the Great Recession of 2007 look like a walk in the park. The real question is whether it's going to be bad enough to be a depression.

One recent poll I saw was asking respondents if the United States was going to have a recession. It's a bit late to be asking that. We are already in a recession, and it's a serious one. Considering the huge numbers of unemployment claims and closed businesses, it's going to make the Great Recession of 2007 look like a walk in the park. The real question is whether it's going to be bad enough to be a depression.The following op-ed is by Robert J. Samuelson (pictured) in The Washington Post. It's worth reading.

When I began writing about economics in the early 1970s, I made a private vow that I would never use the word “depression” in describing the state of the economy. The economists and politicians who occasionally did so were, I thought, engaged in partisan hyperbole. Their game was to scare people into thinking the end of the world was at hand or to pressure Congress to enact a favored piece of economic legislation.

Well, times change. I revoke my vow.

It’s not that I’ve concluded that we’re already in a depression. But we could be. For the first time in my life, I think it’s conceivable. This obviously would be a big deal. It implies permanently higher levels of unemployment (though joblessness would still fluctuate), greater economic instability and a collision between democracy and the economic system.

Since World War II, business cycles have been — with a few notable exceptions — mild and relatively brief. From 1945 to 1990, there were 10 recessions averaging about 10 months each, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), an academic group that dates recessions and recoveries. Some slumps were severe. The monthly postwar unemployment rate peaked at 10.8 percent in late 1982; gluts of workers and products put an end to double-digit inflation.

But even the harshest postwar recessions were tame compared with the Great Depression of the 1930s. There are at least three characteristics that define the Depression and set it apart from postwar recessions.

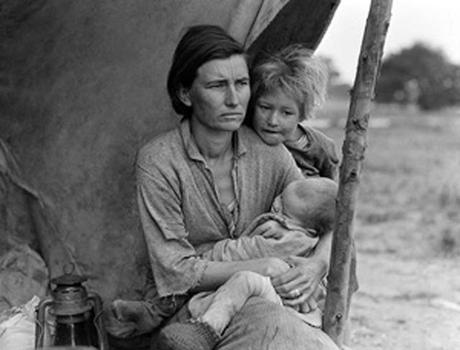

First was the scale of economic havoc and human suffering. In 1933, the unemployment rate averaged 25 percent. For the entire decade, joblessness was in the double digits. There is some technical argument among today’s economists about the precise level of unemployment, but there’s no disagreement that it was huge. From 1929 to 1933, gross domestic product (the economy’s output, or GDP) fell about 25 percent. Defaults on farms and homes were widespread. Industrial output plummeted.

Second, there was an intellectual vacuum in the sense that economists lacked a widely accepted theory to explain the Depression. The prevailing wisdom held that economic downturns would be largely self-correcting. Labor costs and commodity prices would fall, restoring companies’ profitability and enabling them to expand output. But the economy didn’t behave as expected. The Depression kept worsening. Business and political leaders felt powerless. The loss of self-confidence amplified doubts that the economy could recover.

And third, there was, at the outset, no social safety net to cushion the human costs of the economic collapse. As the Depression deepened, one response was to blame the jobless themselves, as historian Robert S. McElvaine notes in his exhaustive “The Great Depression.” The attitude was “there must be something wrong with a fellow who can’t get a job.”

For decades, it has been gospel among economists that another Depression could not happen, because all the underlying causes have been successfully addressed. Yes, economists disagree on some points. Still, there is a broadly accepted theory to control business cycles. Call it modified Keynesianism, after the famous economist John Maynard Keynes. In a recession, cut interest rates and expand the government’s budget deficit.

These steps will stimulate spending and production, preventing an economic free fall. For those who are still unemployed, there is a sizable safety net (unemployment insurance, food stamps, Medicaid) to reduce personal suffering. Public attitudes have shifted. People feel “entitled” to government social protections. This has replaced the sense of shame.

Whatever you think of these policies, they seem to be losing their therapeutic power. We’ve been reducing interest rates and increasing budget deficits for years without protecting ourselves from ever-larger bursts of instability. The Great Recession and current downturn are more virulent than previous postwar recessions. In 2009, we were saved by Congress’s nearly $1 trillion stimulus package and the Federal Reserve’s creation of multiple channels to lend money to besieged borrowers.

Now comes the coronavirus crisis, which makes those efforts seem paltry. Congress has passed a rescue package of about $2 trillion — there are various cost estimates — and the Fed created even more lending programs, presumably channeling more trillions into credit markets. All this has been done in record time. You have to ask yourself: What’s the rush? The answer seems to be that the sheer magnitude of these efforts will reassure the public and financial markets that everything will be okay.

Will it? I don’t know, and probably no one does. But the confidence we once had in our ability to imagine and control the future is fading. Our situation increasingly resembles the early 1930s, when past certitudes no longer match present realities. The dividing line between a depression and a severe recession is murky at best. If we aren’t there yet, we’re closer than at any time since World War II.