Part 3 of the memoir

I have been at home only a few weeks of the long summer vacation when a letter arrives for me from A. It is on thin blue paper with an air mail sticker and it comes from France where he is working for a couple of months. His factory has a mandatory holiday for the Quatorze Juillet celebrations and he has a week off. Would I like to meet him in Paris? Excited by the prospect, I rush to tell my mother, whose face immediately falls. It’s not that she disapproves of A, exactly, it’s more that her maternal instincts have been triggered. This will be the first holiday I have ever spent with anyone other than my immediate family, and my first solo trip with a young man. There are implications.

I met A on the very first evening I arrived in college, and we were more or less a couple by the end of the first term. Determined to meet my parents when they come to collect me for the holidays, he is in my room supposedly ‘helping’ me to pack when they arrive. My parents are a little intimidated. He is 6 foot 4 and talks a lot. Really, a lot. In order to gesticulate better with his hands while talking, he takes the potted Boston fern he has been holding and slides it absent-mindedly onto the top shelf of my bookcase. I watch my parents’ eyes follow his hand. We are all wondering how we will get it back down once he has gone.

It turns out that he lives only ten minutes by car from my parent’s house, and so during the Christmas holidays I pay him a visit. When I arrive, he is not there to meet me. He has been sent to the vegetable garden to harvest something or other in penance for breaking his mother’s milk jug that morning. It’s curious; he looks coordinated but is hard on crockery and downright dangerous around glassware. His family terrifies me because they are so different from any I have known. A is the third of four highly educated, highly articulate, hungry siblings. They talk and eat fast, and a faintly adversarial air hangs around the large kitchen table where we have Sunday lunch. A’s father, who is a sweetheart, takes the trouble to ask my opinion, and I make the mistake of assuming there is time to breathe and assemble an opening sentence. I’ve barely finished the breath before the conversation rushes on in lively spate. Apparently when their grandmother visits, she puts up her hand if she has something she wants to say.

It’s 1987 and there is undoubtedly an unspoken issue of class here. I live on the edge of a modern estate by a Tesco’s superstore. A lives in an old manor house set in several acres of gardens. They have an orchard. When I point this out, A rolls his eyes and protests that it’s a scrubby bit of land with a few apple trees on it. But that scrubby bit of land is the same size as my back garden. A loves watching Grange Hill on the telly as an educational tourist; I never watch Grange Hill because why would I? It’s daily life. His family values tiled kitchen floors, wholemeal bread and dark chocolate. Milk chocolate, I’m told, is for children. My family likes carpet tiles, refined white bread – sometimes with the crusts off – and my mother describes Bournville as ‘cooking chocolate’. I thought my own family had a fairly powerful ideology but it’s nothing compared to the rules and regulations that govern the value system here. There’s a right and a wrong way of doing everything and my instincts are repeatedly wrong-footed.

It’s a relief to leave all these differences behind and return to college, where we are just students in a particular world of our own. But the rules and regulations do seem to follow us. A sits me down and tells me that we are not going to be one of those couples who make their friends feel awkward when they come round. No public displays of affection. He won’t even hold my hand when we walk together on the street, in case we meet someone we know. It’s very confusing as A has pursued me quite hard to reach this point and he does seem to like me. It’s hard to gauge how much he wants this relationship, what it means to him, if he’s committed or not. He buys me a beautiful bag for my birthday and assumes we will go to the May Ball together. But then when we are on the brink of the long summer holiday, he tells me he will be working or travelling abroad for most of it. This is bitterly disappointing, given our proximity outside of Cambridge. My plan is to go home and read as many books as possible in the back garden, and my mother would be devastated if I did otherwise. A’s mother would be devastated if he stayed home underfoot.

What is love to either of us, at this point? What do we think a relationship entails? I’m sorry to say that my idea of romance has been formed by watching The Thorn Birds at an impressionable age. We were all gripped by it in school, and rushed into registration the morning after an episode to compare quantities of tears cried. Father Ralph de Bricassart struggling with the rule of celibacy, ultimately breaking it for love of Meggie Cleary, strikes me as the epitome of passion. At 56, cynical and better versed in the ways of both men and storytelling, it strikes me quite differently. But back then, I believe you measure love by the magnitude of sacrifice made, by the amount of disruption it causes. A, like most self-protective 20-year-old boys, is determined that any relationship he enters will have no material effect whatsoever on his daily life. He’s even been taken aside by one of his former school friends and asked to consider whether, with all the opportunities available to him at Cambridge, he really wants to waste his time on a woman? I know this because he recounted it to me. This is how dumb we both are.

Despite everything, we both believe we can get what we want, and when A’s letter arrives with the invitation to meet him in Paris, I am hopeful. He only has a few days off work and rather than spend them travelling around France meeting relatives – or even perfect strangers – in a way that would please his mother, he is intending to spend them with me, in a way that both his mother and school friend would deplore as a waste of his precious time. That’s good, right?

I don’t discuss any of this with my mother, because what’s preserving the relationship at the moment is the fact I’m too young and unformed to articulate any of my deepest hopes and fears. But my mother is alarmingly insightful. Putting her own feelings aside, she accepts that I will go to Paris and sets about deciding what I will wear. She will show him that regardless of class, income bracket, fancy house, public school education and male mentality, he is punching above his weight.

I’m the most interested in clothes that I’ll ever be, and my mother has loved them and made them all her life. We buy cheap upholstery fabric in a kind of tapestry weave and Mum creates a mini skirt and jacket in a pared-back Chanel style. It is my coolest outfit by far. I set off wearing it on a sunny but breezy day, taking the train to London and then the boat train to Dover. I am that rare creature, a modern linguist who isn’t especially fond of travel. I prefer familiar places and familiar occupations to the new and exotic. Whilst I ought to like museums and galleries and walking tours and cultural sightseeing, and I do like them a little bit, I would almost always rather be sitting somewhere quiet with a book. I have actively tried on recent family holidays to embrace our outings, and I think I’m doing better. In Paris I will simply have to find more courage than I usually possess – I wouldn’t dream of telling any member of A’s family that I ever sat in the back of a car with a puzzle book at a rain-swept beach and found it to be highly satisfying.

When I reach Dover there’s a hitch. I’ve booked a place on a hovercraft because the ferries were all full, but the windy conditions in the Channel mean the boat might not run. While I’m waiting for the authorities to decide, I find a payphone and ring home. My parents will be anxious to hear how the journey is going. I tell them about the hovercraft issue, but almost as soon as I’ve ended the call, the decision is made to go ahead, and I hurry to take my place. I have to run to make my train connection at Calais, but then it is an easy journey to the Gare du Nord.

As the train slows, approaching the station, I see the tall figure of A waiting for me. He walks along the platform, keeping me in his sights as we come to a hissing, grinding halt. Even at this distance from him, separated by the dust spattered window of the carriage, our gazes are locked on each other. Time begins to soften and still. I step down from the train and walk to meet him. The rest of the world falls quiet and empties of people. We are alone.

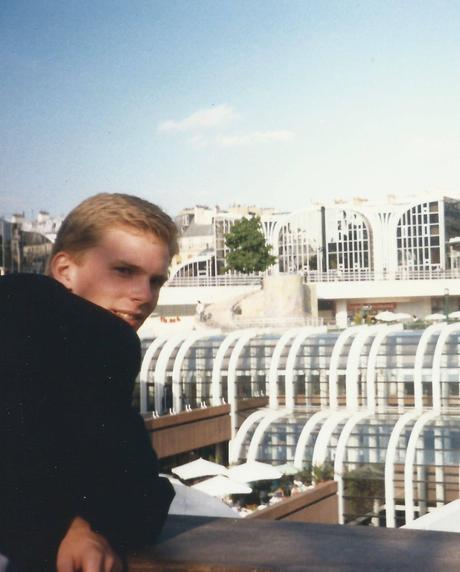

Years later, I will become very close to my sister-in-law who is married to A’s younger brother, and we will compare our romantic experiences. When I tell her that Paris changed everything, she will quip dryly that anything is permitted in A’s family so long as it happens on a different continent. When I remind A of our week in Paris, he will say, ah, that little tapestry suit. We track down our hotel, a poky place with a claustrophobic dark red staircase, our room right at the top. The key won’t open the door and we waste a lot of time finding the concierge and sorting the problem out. Then we walk around the new quartier, lost in each other. Undefined stretches of time pass in this new hypnotic state of connection.

When I finally come upon a payphone and call home, I’m aware that it is early evening, later than I should have left it. I discover chaos; my mother has been worried about me ever since I said the hovercraft might not run, and she is inarticulate and sobbing, unable to be consoled by the fact I am perfectly safe. My father must eventually take the phone from her and he is annoyed by my thoughtlessness, by the fact that I’ve left him to deal with my mother in an extreme state. It is a terrible call. I open the cabin door shaky and upset, but I can’t be the one to ruin the mood with A, who is waiting for me impatiently. We are going out to eat. I must force myself to be calm and normal, and pretend that nothing untoward has happened.

The days we spend in Paris are full. On the Quatorze Juillet we walk down a Champs-Élysées that is bordered on either side by tiers of empty seating as tanks roll through in preparation for the parade. That evening when we try to make our way back to the hotel, the mouths of the metro stations are full of smoke from firecrackers. We walk around the cobbled streets of Montmartre and climb the steps up to the white wedding cake of Sacré-Cœur, its dim interior lit by a constellation of tiny remembrance candles. We visit the Musée d’Orsay, where a huge statue by the central staircase presents a smiling face when we stand beneath it and, by a trick of composition so clever I can hardly work it out, a tragic one as we ascend the stairs. The architecture of Paris offers us an excess of sensual richness. Rococo cherubs wink from billowing plaster clouds, cool marble nudes embrace, their turned backs oblivious to watching eyes, and in the street, the curlicues of wrought iron balconies sinuously entwine.

I’m not used to such long days spent on foot and by the evenings I am so tired and so full of crowds and art and beauty and strangeness that I have no appetite and give half my meals to A. One afternoon, when even A has had enough sightseeing, we find a cinema showing The Unbearable Lightness of Being. We settle into our seats, the row in front of us full of American tourists with their feet up on massive backpacks. The film has been subtitled rather than dubbed but even so, my impressions of it are confused: Daniel Day Lewis whistling cheerfully as he sharpens his surgeon’s saw, Lena Olin outrageously sexy in black underwear and a bowler hat, the translucent beauty of Juliet Binoche’s complexion, her cheeks flushed carnation pink. And then the tanks rolling through the streets of Prague, similar and yet so very different to tanks we had seen only days before on the boulevards. The film’s emotional landscape corresponds perfectly to the way I witness this week in Paris – in a haze that is both intense and fragmented, shot through with a joy that is precarious and oddly close to anguish. What happens on the screen and what is happening in my life, as I sit in my red velvet seat with the Americans sucking coca-cola from outsized paper cups in front of me, feels both intimate and momentous.

We leave our hotel in central Paris and move out to the suburbs to spend a couple of days in a flat we’ve been lent. The flat is empty and echoey, all bare walls and tiled floors. The bed is a mattress on the floor, the kitchen rudimentary. The only standalone item is a huge old black and white television that seems to show nothing other than dubbed repeats of the Six Million Dollar Man. Even so, every time A is left alone for a few minutes, I find him glued to the screen with one hand hovering over the on switch. When he notices me he immediately turns the set off and smiles guiltily. ‘How I grew up,’ he says.

The flat can’t really be described as comfortable, but the pace of life slows, for which I am grateful. There’s no pressure here to be out and about and I can cook simple food for us rather than eat yet another restaurant meal. And so it’s very strange that it should be here that it happens. We go out to the local supermarket, which isn’t very far away, a ten minute walk or so, and as we are walking I become more and more uncomfortable. Anxiety has come from nowhere, a violent, flooding anxiety that I want to wrestle down but can’t. Having the element of surprise on its side, it has overwhelmed me, and panic is only a few shallow breaths away. I’ve been brought up never to let negative emotion show, but this is too much even for me. I am forced to admit to A that something is very wrong. We try to keep going, but I can’t do it and we eventually return to the flat, where gradually the sirens will stop going off in my head and the great tide of anxiety will recede.

I don’t understand what has happened, but it feels like an act of internal terrorism. This is not the kind of anxiety that has a rationale – an exam or an interview, for instance. This was a straight up broad daylight ambush, an attack designed to impress me with its uncontrollable power. I don’t want to make too much of it around A, and he is inclined to dismiss it entirely with a roll of his eyes and an immediate turn to other things. He assures me he is entirely indifferent about it, and it’s obvious he means what he says. I feel an abject gratitude towards him for not having drawn away in disgust and dumped me on the spot. It’s what I would have done to myself, had it been possible.

But I am stuck with myself. We are at the end of the holiday and soon I’m on the train back home. The journey is uneventful, and somewhere around the featureless fields of Normandy my nervous system finally settles. My mother, waiting for me in the kitchen, is torn between ongoing frostiness at my failure to call her and an intense curiosity to hear how things went. I usually tell her everything, but this time I don’t know what to say, and she is disappointed again at my sparse recounting. She eyes me in a way that makes me feel she can read my mind. ‘Well,’ she says eventually, ’I hope you think it was worth it.’

My mother means: I hope the lackluster week you describe was worth the distress you caused me. But as ever, she has hit on something more profound. Was it worth it?

I am in love, and in a relationship that I have no doubt is now serious, the most serious I have ever had. But I have returned with an unexpected souvenir; fear of an outlandish and random anxiety so intense that it’s like falling into the trap of a blackmailer. I’m home and I’m calm, but I know that the anxiety is in my blood. It will return now whenever I have any sense of being trapped in a situation or a demand or an expectation, any place where there is no obvious escape route, any time I want things to go smoothly.

Paris has revealed to me both the love of my life and the greatest issue of my life and the balance of worth is hard to weigh up.

Previous memoir pieces:

Elegy for a Fresher

The Unwild Child